by Rob Persons

The degradation of the city by the car has come to a head as the lack of pedestrian space in urban centres has prevented safe social distancing throughout the coronavirus pandemic. Cities including Paris, San Francisco, London, New York City, Athens, Lima, Bogotá and many more are implementing plans to restrict and/or ban cars in designated areas to enable people to get outside, and to go spend money. In Milan, the Strade Aperte plan announced in April, will transform 35km of roads into cycling and walking space, including 8km of the Corso Buenos Aires, one of Milan’s main commercial streets. The deputy mayor of Milan said this is intended to make more room for people, especially people who shop. A similar plan is being mulled in New Orleans by Mayor Cantrell in concert with the city’s powerful business associations in an effort to ‘recoup revenues lost to the coronavirus’ in the historic French Quarter.

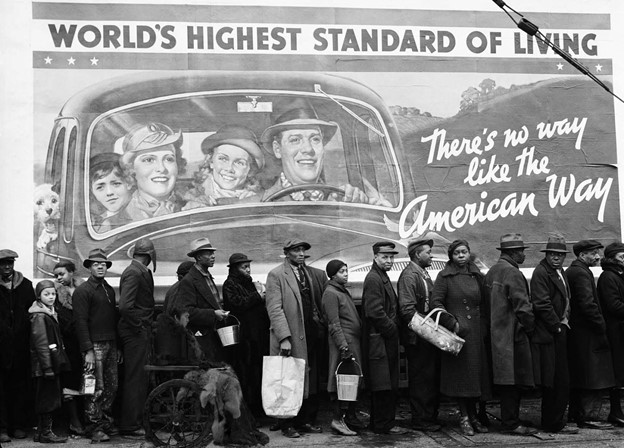

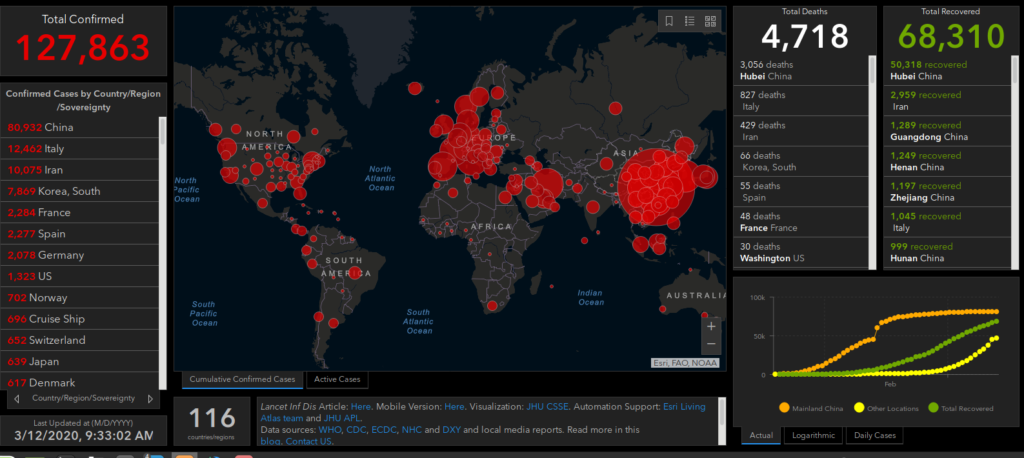

Recently, major publications have been publishing think pieces exalting the benefits of car free cities, lamenting the wasted space, pollution and accidents. In July, The New York Times Sunday Review ran such a piece as a cover article. It made some good points, especially as it rejects ride-sharing and electric cars as realistic solutions to climate change, but was misleading in that it portrays car centred development as a series of mistakes by urban planners or the unconscious result of ‘ethically neutral markets.’ A feature in Bloomberg on the ‘15-minute city’ is even more reason for hope as it focuses on the need for social equity and affordable housing in the transition to ecological cities. Missing from this growing discourse, however, is an examination of the political and economic factors which brought about this car-centred-world in the first place, and how those forces are still in power. In the past, seemingly progressive urban reforms have been used to further cement racial and economic hierarchies. In the United States, epidemics in the 19th century inspired reformers to establish municipal garbage collection, water waste systems, and public health boards meanwhile utilizing xenophobic and classist narratives blaming immigrants (especially Chinese communities), poor people, and the ‘morally corrupt’ for the outbreaks in the first place. Therefore, calls for car free cities should be celebrated with moderation, for if they lack a reconstructive egalitarianism and fail to address the root causes that led to this dubious status-quo, the underlying issues of social and ecological domination will continue to be left for future generations. As we will see, the same extractive economy that brought us the car-centred-world is also behind the growing ecological threat of deadly viruses in what could be a future of global pandemics.

Cars and COVID-19: a political ecology

Viral infection expert Rob Wallace explicitly points to capital backed agriculture, specifically monoculture plantations and livestock feedlots, as the driving proponent in the modern development of zoonotic diseases (like coronavirus) because they homogenize the world’s most biodiverse biomes thereby reducing resilience to disease transmutation. Though the threat of viral pathogens lies most pressingly in the deforestation of tropical regions, Wallace et al. warn,

‘Focusing on outbreak zones ignores the relations shared by global economic actors that shape epidemiologies. The capital interests backing development- and production-induced changes in land use and disease emergence in underdeveloped parts of the globe reward efforts that pin responsibility for outbreaks on Indigenous populations and their so-deemed “dirty” cultural practices.’

We must reject the nationalistic and sinophobic narratives employed by right-wing con artists and duplicitous finger pointers around the world hoping to hide their own complicity. It is vital that we investigate how the capitalist economy drives similar ecological simplifications wherever we are.

We must end our dependence on cars and irrational patterns of urbanisation because the arrogance of the extraction economy is leading us toward climate chaos and a potential future of global pandemics.

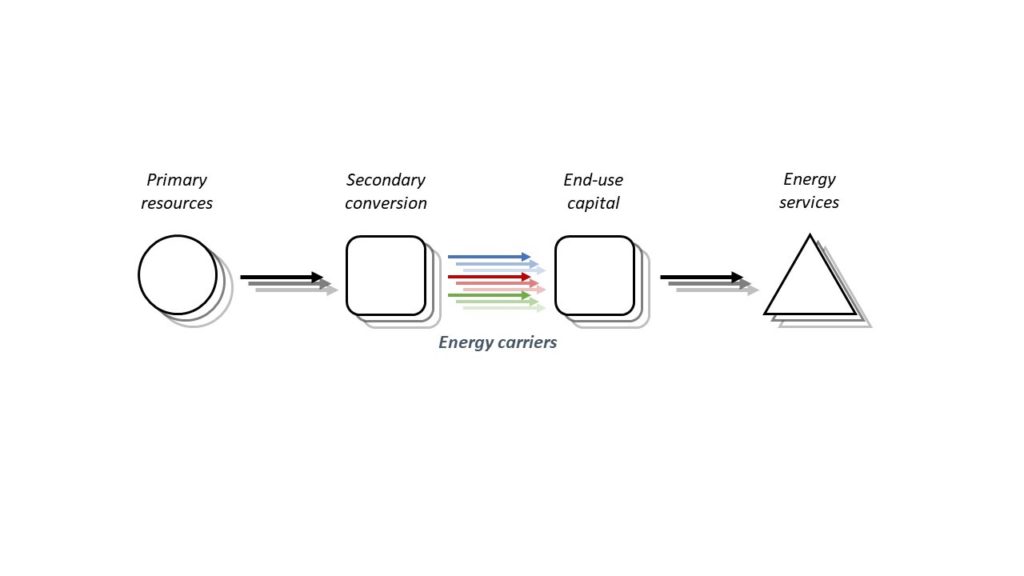

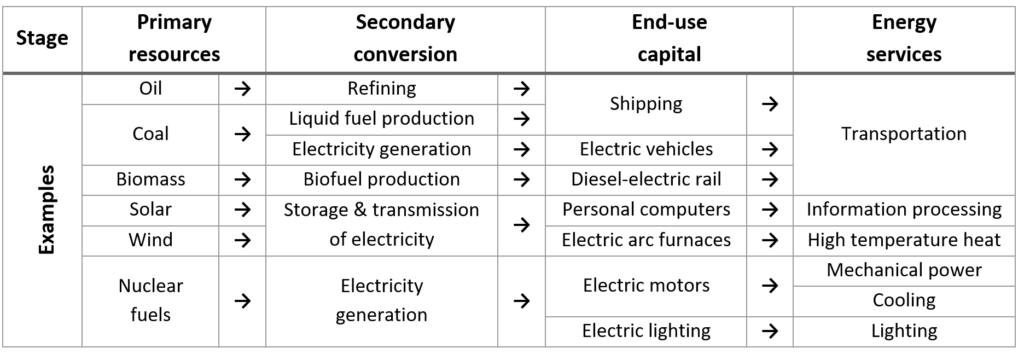

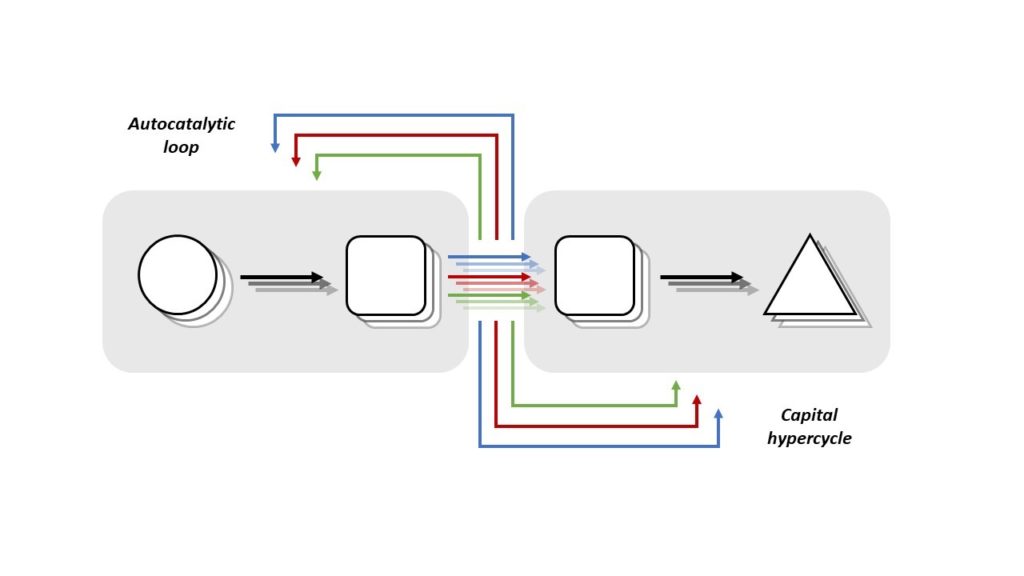

The car-centred-world perpetuates unsustainable land use and loss of natural habitat analogous to industrial agriculture. Compared to public transit or bicycles, the speed and individuality of the automobile requires an enormous amount of space to accommodate, as visualized here. From three lane roads, street parking, expansive parking lots, interstate highways, gas stations, and personal driveways, our built environment becomes an urban sprawl centred around the needs of the car. For example, between 1950 and 1995 land coverage increased by 165 percent in the Chicago metro area despite a 48 percent population increase; meanwhile on the United States eastern seaboard, a continuous sprawl now stretches from Boston all the way down to Washington DC. The car has clogged up and swollen the city, enabling the suburbs to proliferate and deforest the countryside. This type of development fractures ecosystems and communities, leading to a myriad of ecological consequences. The number one irrigated crop in the United States is currently suburban lawn grass, as homeowners are compelled to replace indigenous ecologies with non-native and unproductive grass. Thus suburbs not only increase distances, but also squander the invaded land as the lawn, home, and car consume heretofore unknown quantities from supply chains that stretch the globe. Modern cities and suburbs are designed for cars, rendering alternative transportation either seriously inconvenient or utterly impossible, thus creating a positive feedback loop where increased distances make more people reliant on cars which then require ever more space to accommodate and so on and so forth. Today, many jobs are not even accessible without a car so owning one becomes all but compulsory.

Urban sprawl driven by the automobile, like the plantation and feedlot, leads to fractured ecosystems, reduction of biodiversity, pollution and resource waste. The monoculture, slaughterhouse, city, and suburbs are materially linked by the goods produced at these inhumane institutions which furnish urban supermarkets and stores. But, more fundamentally, they operate under the economic assumption that land and animals are mere resource pools from which to extract value rather than a larger ecology of which humans are a part. Just as we must end the agricultural-industrial-complex, we must end our dependence on cars and irrational patterns of urbanisation because the arrogance of the extraction economy is leading us toward climate chaos and a potential future of global pandemics.

Cars and capitalism: a political economy

One of the most fundamental properties of capitalism is that growth and profit are necessary for its survival. Car-centred transportation is the opposite of cost-effective in terms of aggregate resource use, but it makes better business sense to sell individual cars than to maintain a robust public transit system from a growth and profit standpoint. Since protecting the environment is external to the profit motive, modern development lets the environment be damned. For the capitalist economy, the auto industry is a golden goose affecting so many different markets between steel, rubber, oil, glass, service/repairs, bank loans (debt), and insurance (auto and health). From the consumption standpoint, cars are ever-consuming as the tank must be refilled every 350 or so kilometres, the oil must be changed every 4000, insurance payments are due monthly, vehicle financing collects interest, leasing prevents outright ownership, and god forbid the driver gets into an accident. Much profit to be made.

Cars are useless without roads, making the auto-industry dependent on state funded infrastructure for its basic viability.

The state has played a major role in the creation of the car-centred-world. People often misunderstand the place of governments in the establishment and maintenance of capital markets, for it is commonly assumed that state interference is an opposing force to the so-called free market. In fact, free markets could never have been established without the state’s organization of violence and its funding of infrastructure and high-risk technological research that private firms seeking short-term profit would never undertake on their own. Most famously described by Karl Polanyi, the state plays a vital role in the process of enclosure and dispossession, in which Commons and other pre-capitalist relations are violently crushed and replaced by economic value exchange. In order to create consumers, alternative means of meeting needs must be liquidated.

Cars are useless without roads, making the auto-industry dependent on state funded infrastructure for its basic viability. Ted Steinberg details how the automobile enclosed cities in the United States through a coalition of the state and capital. In the 1930’s, General Motors put New York City’s trolley system out of business before forming National City Lines along with Standard Oil, Firestone Tire and Rubber, and other corporations that profit from car sales. Over the course of several years, National City Lines bought and sabotaged 40 transit companies across 14 states, stifling that ‘healthy competition’ mass transit presented to the automobile. In 1947 NCL was grand juried under the Sherman Antitrust Act and were found to have ‘entered into a “collusive agreement” to monopolize the transit market,’ though the consequences were innocuous fines. Meanwhile, the New Deal doubled road coverage throughout the 1930’s, outspending on roads over public transit 10:1, again tipping the scale of the market. Then in 1956, the Federal-Aid Highway Act sunk $25 billion taxpayer dollars to construct thousands of miles of interstate highways, all but solidifying the car’s spot as number one. These highways were often built on top of prosperous Black communities, like Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans where the I-10 expressway destroyed hundreds of homes and Black owned businesses in the Tremé neighborhood.

David Harvey draws a parallel between this effort to usher in the age of the car and Baron Haussman’s redesign of Paris as they both used the state to prevent dissent by creating jobs building infrastructure that also functioned to isolate the working class. Robet Moses, a major architect of the modern New York metropolitan area, studied Haussman in detail and in his own words ‘took a meat axe to the Bronx’, dividing and isolating many politically active Black and Latinx neighborhoods with the Cross-Bronx Expressway. Harvey points out that the Paris Commune of 1871 repudiated Haussman’s efforts. Today, we are eagerly anticipating a movement to surpass its magnitude in repudiation of capitalist modernity of the likes of Robert Moses.

The commodified city

Two metres of social distancing has exposed how little space there is left for people in cities. Andre Gorz points out in a 1973 essay that while the automobile may appear to provide the individual with transportation independence, it actually makes them more dependent than ever before on the global economy and harmful infrastructure. Many people who drive cannot even identify the basic components of the engine, a far cry from independence. The motorist resembles a perpetual consumer rather than an owner. Now it is not just the worker’s labor, but their very means of existence from which capital seeks to extract value in its unceasing quest for growth. Such commodification would have seemed unimaginable just 100 years ago.

In the city, the car encloses vast space, relegating pedestrians to the literal margins with the physical threat of being run over. Whereas in the past, enclosure of city space took the obvious form of legal segregation or extreme policing to keep the ‘unwashed masses’ out of rich neighborhoods, now obvious repression is obscured by car traffic and commodification (though racialised policing still plays a major role, especially in the United States). Dorceta Taylor explains that once elites realized their methods of racist and classist exclusion through restrictive covenant and court procedure were no longer as effective, ‘businessmen and [elite] urban planning activists collaborated on developing a comprehensive vision for city planning.’ Built infrastructure such as congested roadways and interstate highways were one of the tools used to spatially segregate the rich from poor, Black from white, thereby abstracting individual responsibility for segregation and inequality into the annals of bureaucracy. Systematic intentionality remains camouflaged as dysfunctional policy and poor planning. These impacts are still felt today as many cities in the US are effectively segregated. Now, downtowns are often places of driving, commercial administration, prohibitively expensive apartments (or de facto hotels with Airbnb), and shopping, since the elites who guarded them have moved out to mansions and gated communities in the outskirts of the suburbs. The carceral state enforces this social exclusion by, often racially, criminalizing homelessness, jaywalking, loitering, street art, partying, and other forms of human existence that do not conform to buying or selling. The comprehensive nature of this transition works to conceal alternative systems from the depths of public consciousness, as the niches where counter-hegemonic culture is reproduced like the street corner, independent bookshop, and DIY venue, are increasingly dispossessed by monopoly capital and state regulation (the Bezos and the boot).

We can flip the script and create culturally vibrant, equitable, and ecological cities where human beings can flourish in participation with the natural world.

The city has been partitioned and impersonalised into sectors and sections of work and consumption so many people no longer know the names of their own neighbors. Of the many paradoxes Andre Gorz points out, one of the most tricky is that in order to defeat the car we must love our cities, but the car has killed the city so it becomes almost impossible to love. Meaning, it is not enough to invest in more public transit, bike lanes or ban cars in certain areas if the city has no soul. If people don’t take joy in being outside, if the communal ties which foster a multicultural society are not repaired and extended, if speed and quantified economic value remain prioritized over ecological and social well-being, then we will continue to choose the convenience and isolation of the automobile. Things do not have to be so bleak, however. Through a democratic process that centres human and ecological well-being, we can flip the script and create culturally vibrant, equitable, and ecological cities where human beings can flourish in participation with the natural world.

Which way forward: Cul-de-sac or community democracy?

Ground has been broken on Culdesac Temple, soon to be a completely car free community of up to 1000 people in Temple, Arizona. The $140 million, 16-acre development featuring 636 apartments and 24,000 square feet of restaurant and retail space is set to open in 2021. The website boasts a quaint design targeting young professionals looking for a living space without all the negatives of the automobile. Residents will have access to on campus grocery stores, hair salons, coworking spaces, retail stores, and even a wine bar. Without cars, there will be ample greenspace for residents to enjoy with access to commuter rails, shuttle busses, and bike shares making transportation easy. Located just east of the city of Phoenix, Culdesac appears to be an ecological heaven for people who want to live life to the fullest. This development shares some superficial similarities with the community described in Kate Aronoff’s visionary article about the potential future of a successful Green New Deal. The difference? Culdesac represents a future for those who can afford it, while Aronoff’s community represents a future for all.

It brings me no joy to point out that much of these so-called solutions wrapped in tech-industry branding and backed by venture capital are little more than marketing gambits designed to make people who can afford them feel less guilty about their own consumption habits. Plopping a development whose ‘goal might be termed instant gentrification’ and thrives on the ‘business climate of weak trade unions’ is never going to bring about ecological equity, cars or not. While developments like Culdesac may appear to be ‘green’, it is a fool’s gold as the ecological and economically exploitative impacts of the labor, electricity, food, building materials, water waste, plastics, exclusion of poor folks, et cetera are externalized, out of sight and out of mind. Yet mainstream media never misses a chance to laud the tech bro personality cult for their ‘innovative’ approaches to further commodification. Like electric cars and ride sharing, these false solutions do not touch the structural roots of the problem. Neither is it hard to imagine future such communities built behind walls with armed guards, reminiscent of Octavia Butler’s climate sci-fi novel Parable of the Sower.

As we rethink the city throughout this pandemic, we must ask: Do we want cities designed for the rich to enjoy restaurants, parks, shops, and lush bicycle greenways while the poor serve, sanitize, and enjoy not but the scraps? While I have been critical of the recent coronavirus inspired car restrictions as they fail to present comprehensive solutions, they have also led to some positive outcomes. At their worst, we see them oriented toward further commodifying social relations and creating space only for the enjoyment of those who pay. But at their best, these open street policies have given people who faced lonely weeks cooped up in their apartments the opportunity to go out and see friends, attend socially distanced events, and enjoy their neighborhoods. It has even inspired residents that may once have been strangers who happened to live near one another to become real communities. On 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights New York City, neighbors came together to organize to open up their block. Since then, they’ve connected with each other as they share skills and hobbies and just hang out, perhaps beginning to restitch the social fabric needed to overcome Gorz’s paradox to build the new world in the shell of the old.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, the increase of displaced peoples, infertile land, rising tides, severe weather events, and viral infections will create conditions which require institutions of pluralistic democracy and economic equality or else doom us to a future of climate apartheid and famine. The way we travel plays a major role in this. Shortening distances and making public transportation, cycling, and walking as convenient, reliable, and aesthetically pleasing as possible should be a central objective of urban policy. But it is more than a question of lifeless infrastructure. As space is increasingly privatized and locked away behind high-tech surveillance, reclaiming the city for all is a vital step toward a common future. Clearly, status-quo politics are perfectly happy to let the most vulnerable people suffer and die. The socio-political conditions in which an environmental disaster occurs have a significant bearing on the severity and distribution of the harm it causes, therefore we must ensure that our future hardships are dealt with by new revolutionary institutions based in social and ecological equity, integrity, and fairness. To achieve this, the city must be re-envisioned as a body politic rather than an impersonal amalgamation of infrastructure and isolated individuals in order to counter monopoly of capital as it commodifies existence and the Nation-State as it centralises and bureaucratises political decision-making for benefit of business interests over people and planet. It is imperative that we re-embed the social and productive functions of the economy back into a democratic and social realm, recovering the shards of humanity shattered by this fucked up capitalist economy with each passing day.

Rob Persons is a writer and construction worker based in New Orleans. You can find him reading books in the park.