Who can ignore that the Olympians of the new bourgeois aristocracy no longer inhabit. They go from grand hotel to grand hotel, or from castle to castle, commanding a fleet or a country from a yacht. They are everywhere and nowhere. That is how they fascinate people immersed into everyday life. They transcend everyday life, possess nature and leave it up to the cops to contrive culture.

—Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” 1968

by Sasha Plotnikova

I first started hating the Olympics as a student in Montreal, a city filled with the carcasses of stadiums, pavilions, and decaying detritus of mega-events held there in the 60s and 70s. The year before I moved there marked the 30th anniversary of the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympics, as well as the year that the City finally repaid the $1.5 billion (CAD) of debt they were left with after the Games.

For cities hosting the Olympics, debt is a matter of course, and the legacy of the Games is palpable: entire neighborhoods are ripped from the urban fabric so that hotels, empty stadiums, and Olympic villages may sit in their place. The social, cultural, and financial weight of these white elephants is shouldered by long-term residents. Two weeks of fame for starry-eyed local politicians and Olympic boosters amount to a pressure-cooker of exploitation and state violence for those whose lives, labour, and culture make city life possible.

But a counterpart to this history of destruction is a lineage of struggle, survival, and solidarity. While the fight against the Olympics has historically taken place at an immediate, local scale, today’s anti-Olympics organizing is beginning to coalesce into an internationalist movement for the right to urban self-determination.

Bigger than the Olympics

In Los Angeles, a group of organizers working together under the banner of NOlympics LA are fighting for the cancelation of the 2028 LA Olympics and the abolition of all future Games. And that’s only their short-term goal.

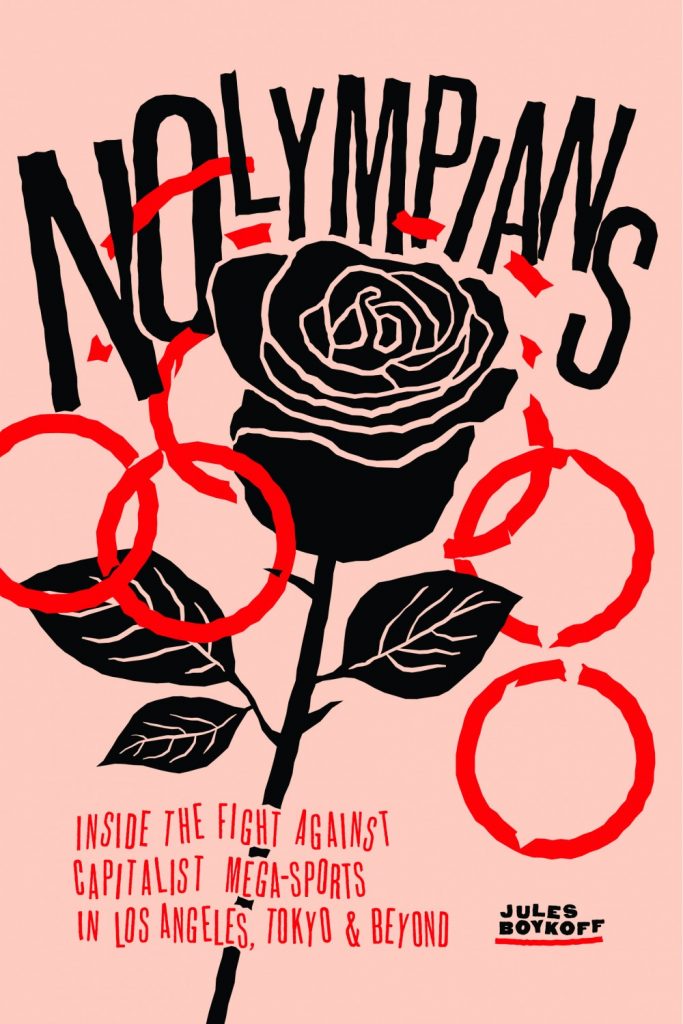

In NOlympians: Inside the Fight Against Capitalist Mega-Sports in Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Beyond, Jules Boykoff follows the work of NOlympics LA, contextualizing their fight against the 2028 Games in LA within a global movement to expose and combat the effects that transnational capital has on the daily lives of poor people living in cities.

As an active member of the LA Tenants Union (a supporting partner of NOlympics) and a hater of the Olympics myself, I’ve observed first-hand the group’s constant churn of actions, teach-ins, and community canvasses since their founding in 2017. But the larger significance of groups like NOlympics can be hard to see up close, and is often obscured by the fervour of organizing around immediate crises at the local scale. As I explore later, the NOlympics activists have developed an arsenal of popular education tactics that create a gateway to local organizing. Boykoff’s snappy yet poetic prose captures their spirit and teases out the long-term promise of mounting a campaign against specific, local issues. Ultimately, the book’s greatest contributions are the lessons it offers on the relationship between international solidarity and local action.

Himself a former Olympic soccer player, Boykoff has spent the past decade building critical analysis about the Games. This shows: the text weaves seamlessly in between interviews with the activists and the lessons that inform their politics. To underline the deep socioeconomic inequalities facing Angelenos, the book throws into stark relief the disparity between the priorities of the oligarchs behind the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the demands of the communities that are displaced and criminalized by the Olympics.

The book is written in four parts, moving from the history of the Games and the destruction they bring; to the origins of NOlympics and the significance of the rise of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA); to the way their local strategies fit into an internationalist movement; and finally to some conclusions for what is to be done about the Olympics.

Throughout, Boykoff situates their organizing within the long-time work of adjacent grassroots organizations in LA and within the praxis of past and present social movements globally. Boykoff’s account of the NOlympians’ trip to Tokyo demonstrates that it’s only through building international connections that the activists are able to connect the local to the global.

Seizing the means of the production of urban space

To understand why the Olympics are bad for LA, you have to understand why capitalism is bad for cities. As David Harvey explains in his book Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, urbanization — the visible arm of endless economic growth — was never anything other than a project of power. Cities develop as economic hubs, where what looks like an abundance of financial opportunities to politicians and investors, signals an ever-worsening quality of life for poor and middle-class residents. Each time the economy sees a boom, poor communities see an intensification of urban stress. As neoliberalism has dug in its heels over the past few decades, the gap between the rich and the poor has become most pronounced in cities.

Perhaps more than any other city, Los Angeles embodies the economic order that has come to define what it means for a place to be urban. The process of urban growth goes in lockstep with the growing burden of rent; the planned obliteration of public housing; the demise of labour unions; the stagnant wages; the proliferation of ever-new forms of segregation; and booms in the most precarious and informal branches of the economy. The lived experiences of millions of Angelenos are proof that the very machinations that spur economic expansion and urban development are the ones that make it increasingly impossible to live in cities.

Land speculators and real estate developers have been particularly pervasive throughout the city’s history. When they’re not at the helm of the city’s economy, they’re in the ears and pockets of politicians, laundering their projects through green-washing and transit-oriented gentrification policies.

The history of urban uprisings in LA has kept pace with this history of injustice. The city’s growth has been enabled by its entrenched culture of white supremacy, which has incensed urban movements from the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots; to the Watts Rebellion in 1965; the 1966 high school boycotts; the Chicano Moratorium in the 70s; the 1992 uprisings in the wake of the brutal police beating of Rodney King; and today’s Black-led demonstrations against police violence.The economic crisis faced by low-income residents is growing steadily, and with it, more and more people are starting to organize to take back the cities they’ve built and made their lives in. Whether that fight coalesces in an alliance against the Olympics or manifests in the daily work of tenant organizing, it’s a fight for the right to the city.

The movement for the right to the city was first given its name by Henri Lefebvre, on the 100th anniversary of the publication of Capital and on the eve of the urban social movements of May 1968. Lefebvre’s writing presaged what would take place in the last decades of the 20th century: the global rise of urbanization and the concentration of capital in the world’s cities. Since his time, urban centers like LA have increasingly become the places where the effects of a profit-driven housing system are most deeply felt: urban planning policies are written with the intention of displacing the poor and replacing them with higher-income, whiter residents — all so that the economy can continue to grow and attract ever-wealthier tourists, investors, and residents to the city. This process has irreversibly changed the look, feel, and spirit of cities to embody the sterile, generic luxury that caters to the global elite.

With this dark horizon in sight, Lefebvre wrote about the urgent need to fight for an urban life that centers poor communities, promotes a sense of belonging, and imbues the everyday with meaning and novelty—he called this the right to the city.

One of the most important takeaways of Henri Lefebvre’s “Right to the City” is the proposition that already in 1968, Marxism’s focus on the worker as the agent of social change no longer held the same ground as it did in the 19th century. In response, Lefebvre suggested that the task at hand is to seize the means of the production of space, updating the Marxist focus on seizing the means of industrial production. To claim their right to the city, tenants, street vendors, immigrants, service workers, artists, and those who care about and enliven public space would take back what they’ve created and nourished.

Human rights, as they’re understood by most, are underwritten by the notion of private property, and this makes the proposition that the city, or even housing, is a human right, for instance, a difficult pitch. The right to the city complicates that understanding: it’s not just about a right to resources— it’s about a collective right to self-determination through the built environment and the urban social realm.

For Lefebvre, the right to the city was the assertion of the right of low-/no-income residents to shape the city so that it might both fulfill their basic needs and better reflect their culture and desires. Without this right, anyone who isn’t identified as part of the white middle and upper class is targeted by social cleansing campaigns through evictions, rent gouging, policing, and surveillance. The right to the city is a fight for safe, affordable, and decent housing; for public amenities; for bountiful, accessible, unsurveilled and unrestricted use of public space; and ultimately, for avenues towards community control over the built environment.

A renewed interest in what Lefebvre articulated in 1968 has taken two paths. While it’s been embodied in the daily struggles of autonomous grassroots movements; it has also been opportunistically adopted by nonprofits as a brand. The nonprofit approach amounts to asking for a seat at the table by promoting community engagement and public meetings that in theory, offer an avenue for poor people to participate in urban planning. But even when long-time residents of gentrifying communities are invited to conversations between developers and city agencies, their presence is tokenized and their participation is superficial by design.

A grassroots right-to-the-city approach like that of NOlympics, on the other hand, offers an avenue for organizing against the abstract forces of neoliberalism by making clear demands for material changes that can improve the lives of poor people.

For an in-depth look at the renewed relevance of the right to the city in today’s anticapitalist movements, we can turn to David Harvey. He suggests that a primary obstacle to finding “our version of the [Paris] Commune,” might be the Left’s failure to collectively trace the connections between seemingly separate struggles, within our towns and cities and around the world. For him, it’s only through an internationalist movement that understands racial, environmental, economic, and spatial justice as facets of the same struggle, that we can begin to reclaim our cities. The promise of the global anti-Olympics movement is just that: an international, intersectional coalition rooted in local struggles for cities where the well-being of residents holds more weight than a two-week mega-event for the ultra-rich.

The long road to Olympic abolition

The Olympics produce a state of exception that allows municipal politicians around the world to usher in the version of the city they want but can’t get through a democratic process. Local police forces take advantage of this moment to acquire otherwise-unattainable funding, weapons, and legal protections. Host cities bend over backwards to accommodate a two-week mega-event, permanently altering their urban fabric and pricing out longtime residents. In Boykoff’s words, “It’s not just that poor people are not given a seat at the Olympic table — it’s that they’re the meal.” The same pattern plays out again and again, from Rio, to Sochi, Beijing, and LA. In the years leading up to the return of the Olympics to Los Angeles in 2028, we can expect nothing less than the exacerbation of the very demonstrations of white supremacy and aspirations for cosmopolitanism that have pushed communities of colour out of the neighbourhoods they’ve called home for generations. Already, we’re seeing the expansion of the LAPD; more transit-oriented displacement; hotel development; and rising rents.The 2028 Olympics represent the most recent incarnation of racist and anti-poor planning, and their arrival fans the flames of LA’s urban crises.

In 2017, NOlympics was born in the Housing and Homelessness committee of DSA’s Los Angeles chapter, which was unique in that it actively pursued coalitions with existing organizations led by long-term residents organizing with tenants and unhoused communities. This origin story is an important piece of the book, and Boykoff’s description of NOlympics’ relationship to DSA-LA further illustrates NOlympics’ commitment to long-time local struggles and international coalition-building. Since their founding, NOlympics has gained a relative autonomy from DSA, and gathered together a coalition of over 30 local grassroots organizations.

The day-to-day organizing of NOlympics LA is handled by a handful of dedicated, core activists, many of whom have been with the group since the beginning. But much of their base draws from the members of their coalition partners, which themselves benefit from having a shared forum for building solidarity, and a long-term goal to mobilize against. By strengthening those alliances, the group has planted roots in LA’s ongoing and wide-ranging struggles, from racial justice, to anti-imperialism, housing justice, and many more.

In effect, the group has embedded itself into grassroots organizations outside of DSA, learning from them, supporting them, and funneling new DSA members into these movements—responding to a common critique that DSA lacks those kinds of connections. As I’ve seen for myself, NOlympics organizers consistently show up to support protests at the homes of slumlords organized by the LA Tenants Union. They help to monitor encampment sweeps and empower unhoused residents with Streetwatch LA (another DSA-LA working group with relative autonomy), and turn up for direct actions organized by Black Lives Matter against the city’s record-high rate of police murder.

Similarly, NOlympics maintains a level of porosity and agility that welcomes new members on a regular basis and draws activists from different backgrounds to partake in their actions, which largely revolve around tactics of popular education: canvassing, polling, and teach-ins. By pulling together the already-existing expertise and analysis of local organizations, and setting out on a decade-long mission, NOlympics stands a chance of winning the cancelation of the LA2028 Games. More importantly, they’re ensuring that the city’s activist groups have a constant platform where they can come together, and that new members of DSA have an avenue for involvement in ongoing anticapitalist work in the city.

Yet, for NOlympics, coalition-building is not just a tactic for mounting a localized intersectional critique of the effect of the Games on LA. It is also a project of international solidarity to end the Games for good: “No Olympics Anywhere.” The activists recognize that without lasting solidarity between host cities, all the work done in each host city is lost when the IOC moves on to its next victim. In response to the IOC’s globetrotting caravan of destruction, anti-Olympics activists around the world are beginning to strategically organize on a transnational scale. Fostering this coalition of global anti-Olympics groups has become a central initiative of NOlympics, responding to another shortfall of DSA, which is its lack of an anti-imperialist analysis.

Last summer, Boykoff traveled to Tokyo with NOlympics for the first major international anti-Olympics summit, where the activists from different cities around the world convened and marched with the local anti-Olympics organizers of HanGorin No Kai ahead of the Tokyo 2020 (now 2021) Summer Games. There, NOlympics organizers shared the particular ways that transnational capital manifests in LA. Boykoff, when narrating this trip, also observes the hurdles to this scale of organizing: if language barriers weren’t enough, different cultures of organizing can make collaboration difficult. But there were important lessons learned as well. Back in LA, the Nolympics organizers constantly remind local activists that their enemy is not just the LA City Council, but a transnational regime of neoliberalism.

As David Harvey notes, “The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city.” NOlympics’ answer to this is building a coalition that unites antiracist, anticapitalist, anticarceral, and anti-displacement organizers in the fight for their right to continue to live in and to shape the city — from LA to Tokyo and beyond. It offers lessons about the importance of local, intersectional solidarity to activists abroad; and informs the work of local activists with an internationalist analysis. NOlympians depicts a coalition of organizations that prefigures a version of Los Angeles where none of us are free until all of us are free; where the city’s racist history is top of mind as we steer the ship towards racial justice; and where solidarity plays out in everyday acts of mutual aid.

A gateway to organizing

Like DSA, NOlympics takes an inside-outside approach, agitating politicians in the city hall chambers while building power by organizing with their coalition partners. However, NOlympics’ unabashedly abolitionist mandate sets it apart from what Boykoff identifies as the “socialism by evolution not revolution” mandate embraced by much of DSA — instead of reform, they want an obliteration of the capitalist mega-event. Their positioning creates a bridge for new members of DSA to get involved with community organizing beyond electoralism.

One way NOlympics has done this has been by perfecting the art of transfiguring cynical criticism into demands for positive change. They do this by exposing the failures of local government through gripping online satire, and pairing it with rambunctious, theatrical direct actions. Boykoff describes the ways in which NOlympics responds to the specific cruelties and political failures of contemporary Los Angeles. LA’s municipal government puts much of the city’s political power in the hands of the city council, while, as the NOlympians relentlessly point out, Mayor Eric Garcetti is often nowhere to be found. Before devoting much of his time in office in 2018 to courting a long-shot presidential bid, he signed the host-city contract for the 2028 Olympics without any input from the public—a clear tell that the 2028 Games were never intended to benefit the average resident of LA, but that they’re meant to serve the private interests of hotel developers, real estate speculators and international corporations that thrive on the tourist class.

Garcetti and LA City Council have consistently upheld racist and anti-poor policies. White supremacy is deeply ingrained in the city’s planning history, and wealthy, white residents look to the city council for leadership. The summer of 2019 saw an uptick in anti-homeless white vigilante violence after the city council reinstated a ban on vehicle dwelling. Backed by the most murderous police force in the nation, politicians and vigilantes alike are already on a campaign to sanitize and pacify neighborhoods across Los Angeles. The decaying local media landscape only makes matters worse, with Pulitzer-prize nominated journalists writing poverty porn, and the chairperson of the 2028 Olympic bid holding a major stake in one of the few local outlets.

In response, the NOlympians have produced their own media. Whether members are writing about the history of stadium-driven displacement in LA, making a guide for how to report on the Olympics, or making explicit the links between 1984 LA Olympics and the militarization of the LAPD, one of the central tenets of their work, according to activist Anne Orchier, is to “chip away at the Olympic movement as a whole.”

Boykoff describes NOlympics as a “perpetual praxis machine,” and their organizing takes many forms, ranging from performatively canceling the Olympics on the steps of LA’s City Hall; to holding auditions for actors to fill Garcetti’s shoes in his frequent absence; to doing outreach in public spaces and areas most impacted by hotel development ahead of the Olympics. Threading together all of these tactics is the activists’ trademark humour, which makes their cutting political criticism more approachable. While people may not know exactly how to critique something as abstract as global capital, NOlympics shows them how and empowers them to do so. Their propaganda pairs criticism of the profit-driven political economy with people-centered alternatives, all in plain language grounded in the specific issues facing Angelenos.

Popular education is at the root of their approach to organizing, and as Boykoff observes, their regular meetings have become more about training people to organize, and less about report-backs and updates. Their organizing mandate seems to be not base-building, but creating an environment for organizers to grow and learn from one another, and connecting new DSA members with existing organizations working on specific issues in Los Angeles.

No Olympics are Good Olympics

If you ask any of the NOlympics LA organizers whether the Olympics could be reformed to better serve local communities, they would be quick to say that no Games are good Games. They would tell you that what powers the Olympic machine is the IOC’s determination to trample on poor communities in cities across the world, just to turn a profit, get back in their private jets, and do it all over again somewhere else.

Yet, after chronicling the work of these organizers, and explicitly reiterating their abolitionist platform, Boykoff lays out some suggestions for Olympic reform. For one, he suggests an independent panel to review bids, and proposes higher environmental oversight. He imagines an Olympic machine turned on its head, so that funds that circulate up through the Games into the hands of oligarchs may be redirected into marginalized communities instead. He also proposes that the IOC follow the lead of FIFA, making votes for the Games public.

It’s perplexing that after following the NOlympics organizers’ analysis so closely to their unapologetic, no-compromise demands for the eradication of the Olympic Games, Boykoff suggests reform. He implies that the IOC would be open to positive change; and furthermore that these reforms would not later be corrupted. It’s difficult, knowing what we’ve learned from his book, to imagine that a reorganized IOC would stage anything that truly benefits the no- and low-income communities of host cities. Boykoff’s propositions prompt an important question for the anti-Olympics movement and for the fight for the right to the city: How far can reform really go?

The NOlympians have rejected the premise of this question altogether. NOlympics is about ending much more than the Olympics, and spending energy on fighting for reforms to a system premised on the disenfranchisement of communities of colour and the banishment of the poor, might be something better left to the nonprofits. Instead, NOlympics has highlighted moments in sporting history when athletes got together to organize ethical, people-first events. For example, their video A Brief History of Swolecialism gives an overview of the Workers’ Sports Movement. The 1932 International Workers’ Olympiad famously drew more visitors and competitors than the concurrent 1932 LA Olympics. That legacy lives on today in CSIT (Confédération Sportive Internationale Travailliste et Amateur, or International Workers and Amateurs in Sports Confederation), which offers an alternative to the IOC that goes unmentioned in NOlympians. Boykoff writes about these alternatives elsewhere, but misses an opportunity to connect the dots between NOlympics LA’s fight to abolish the Games and their enthusiasm for the potential of a democratic sports culture led by poor people.

Ultimately, the more important question at the end of this book remains unasked: what kind of city would it take to put people before profit, and to democratize sporting culture? What kind of city would it take to invest in and preserve bountiful public recreation space, provide clean water to swim in, and safe streets where kids can play — all without displacing long-time residents? It’s the kind of city that the partners of the NOlympics LA coalition are already fighting for and beginning to enact.

What the NOlympians are doing, and what Boykoff chronicles so well, is building a coalition of organizations in LA that are collectively fighting for their right — the right of regular people — to the city. In a global city like LA, this fight is up against the influence of transnational real estate investment, the tourism industry, and sportswashing. Though it’s difficult to measure the progress they’ve made towards getting the 2028 Games canceled, they’ve become a vital voice of dissent in our city hall chambers; a constant well of research and analysis while local media sleeps at the wheel; and an important common ground for groups fighting for environmental justice, tenants rights, Black liberation, and demilitarization. Boykoff illustrates not only the contemporary relevance of a right-to-the-city campaign; but the importance of far-reaching, collaborative, and coalition-based organizing that pairs single-issue struggles to general ones and local fights to the global fight against capitalism. The NOlympians are flipping the script, taking what engineer William Mulholland once said to the mayor at the opening of the Los Angeles aqueduct, and broadcasting it to the city instead: “There it is! Take it!”

All photos courtesy of NOlympics LA.

Sasha Plotnikova is a writer and design critic living in Los Angeles. She organizes with the LA Tenants Union and has taught architecture at Cal Poly Pomona. She tweets at @sashaplot_.

NOlympians: Inside the Fight Against Capitalist Mega-Sports in Los Angeles, Tokyo and Beyond by Jules Boykoff is available from Columbia University Press.