by Apoorva Dhingra

Cities across the world comprise only 2 percent of the land, but account for 70 percent of the global GDP, over 6 percent of global energy consumptions, and 70 percent of global greenhouse emissions. Their high economic and ecological impact coupled with unprecedented rates of urbanization prompted the New Urban Agenda adopted at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) to declare urban planning to be a critical driver and tool for achieving equity and sustainability and enhancing economies.

But in 2021, as the world’s cities struggle to contain and recover from COVID-19, the opposite is happening. Canonical urban planning is failing on all grounds. From Delhi to Lagos and from Jakarta to Rio De Janeiro, heightened inequality, displacement, lack of public health infrastructure, and land-grabbing have become common accompaniments of urbanization.

In India, which is the focus of my urban enquiries, the failures of canonical urban planning are playing out through Master Plans which have dictated cities’ development trajectories since colonization. But contrary to common critiques, most planning failures are not a result of improper or inadequate implementation of the Master Plan. Rather, as Gautam Bhan—an urban scholar and activist from Delhi—puts it, they are an intrinsic part of planning’s logics, conceptions, and practice. Master Plans, and canonical top-down urban planning by which they are dictated, produce retrospective illegality and promote mainstream development centred around economic growth and production over the needs of the urban majority.

For decades, planning was touted as an objective discipline—a means and method through which to anticipate, manage, and respond to urban growth. While it is considered a scientific-rational process that is free from politics, urban planning has in fact always been about the existence of power, as the power/knowledge analysis of political philosopher Michel Foucault can illuminate.

Urban planning in India: a colonial and imperial enterprise

Master Plans, which are developed by urban local governments, have emerged as the standard planning instrument in India since 1962. Mandated by the Town and Country Planning Acts of various Indian states, they conceive and dictate the physical and socioeconomic development of cities 20-25 years into the future. At present, around 2000 Indian cities—about half of total cities in India—have Master Plans. However, despite their popularity and supposedly new solutions to current problems, Master Plans have a rich colonial and imperial history that contributes to their failures.

Town planning in India was first introduced under the Bombay Planning Act of 1915 when colonial authorities were struggling to contain plague epidemics which, according to them, were a result of ‘insanitary labyrinths of the native city.’ As part of these acts, the British created trusts to lead large-scale demolitions, streamlined the process of land acquisition for commercial and infrastructural purposes, and laid provisions for financing urban development. While the Bombay Planning Acts of 1915 and its subsequent iterations did not create the Master Plan, the ‘town planning schemes being prepared today continue to follow a template laid out nearly a century ago by very different institutions operating in an entirely different context.’ Post-independence India’s planning frameworks with their emphasis on white-field development, order and beautification, are an adaptation of the British town planning systems that foremost served the economic and social concerns of the Crown.

In addition to colonial influences, Ford Foundation and American planners also played a great role in shaping planning ideologies in India after independence. Prompted by the jaundice epidemics of 1955-56 in Delhi, Amrit Kaur, the Minister of Health, approached the Ford Foundation and sought its help in managing the capital city’s ‘haphazard growth.’ According to historian Gyan Prakash, the focus on the epidemic was telling as it echoed the colonial discourse on urbanism and permitted the postcolonial elite to frame city planning as a biotechnical enterprise to clean the environment, rid it of diseased spaces, and configure it as a rationally ordered space.

Master Plans as methods of control

Against the backdrop of the Indian government’s demands for ‘rational land use’ and ‘clearance of slums’, the Ford Foundation created the first ever Master Plan for Delhi (MPD) that was adopted in 1962. This plan proposed to manage ‘sprawl’ with a green belt and strict zoning between commercial, residential, and industrial areas, to divide the city into cellular neighborhoods, and to establish satellite towns so as to limit the inflow of population into Delhi. Without any input from Delhi’s residents, many of whom lived where they worked and enjoyed the intimacy that came from densely populated neighborhoods, Delhi’s cityscape rapidly changed to propel the city into modernity. According to sociologist Amita Baviskar, Delhi’s first Master Plan ‘envisaged a model city, prosperous, hygienic, and orderly, but failed to recognize that this construction could only be realized by the labor of large numbers of the working poor, for whom no provision had been made in the plans.’

The anti-slum and anti-poor biases of MPD ’62 were especially sinister given the Partition of 1947 that displaced over a million people to Delhi who had to be accommodated in bastis (basti comes from the Hindustani word basna which means ‘to settle’ or ‘to inhabit’). By dividing the city into regulated and segregated use zones, many of these settlements were designated as unauthorized and sometimes illegal, which made their residents’ occupancy even more precarious. The Master Plan, thus, created illegality where it did not exist. In contrast to the slum, a settlement is considered authorized/planned only when it is built on land notified within the development area of the Master Plan and zoned as residential. Yet no new land was notified as an urban development area by the Delhi Development Authority—the apex planning body in Delhi that creates the Master Plans—between 1962 when MPD ’62 was issued, and 1990, when Delhi’s second Master Plan, MPD ’01, was issued. By the late 90s, the city’s population increased by 3.4 million people, well beyond MPD ’62’s demographic projections. This rising population could not wait for the plans to catch up and organically settled beyond the Plan’s notified areas. Yet, subsequent Master Plans of 2001 and 2021 still chose to not designate these already built-up areas as authorized development areas. It is for this reason that Gautam Bhan asserts that planning produces and regulates illegality as a ‘spatial mode of governance’, making it a part of its logics, conceptions, and practices.

Just as Master Planning is rooted in colonial history, discourses and practices, so are the ideas of development that they promote in Indian cities. This is well illustrated by Evita Das’ analysis of the 2035 Master Plan of Srinagar, the capital of Indian occupied Kashmir. The plan aims to remake Dal Lake—the most popular tourist site in Srinagar—and introduces Special Investment Corridors to kickstart the development of the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. By envisioning Dal primarily as a tourist site, the plan aims at beautification via gentrification. It views Dal’s inhabitants as encroachers who need to be relocated away so that shikara—typical wooden boats found on the lake—gateways, cycle tracks, organic farms, and water sports facilities can be introduced to raise the lake’s stock as a tourist site. When viewed in the context of India’s occupation of Kashmir and the abrogation of the territory’s special rights, the 2035 Master Plan’s remaking of the Dal Lake and viewing of Kashmiri inhabitants as mere subjects that can be moved around for developmental goals are a clear exercise in colonization.

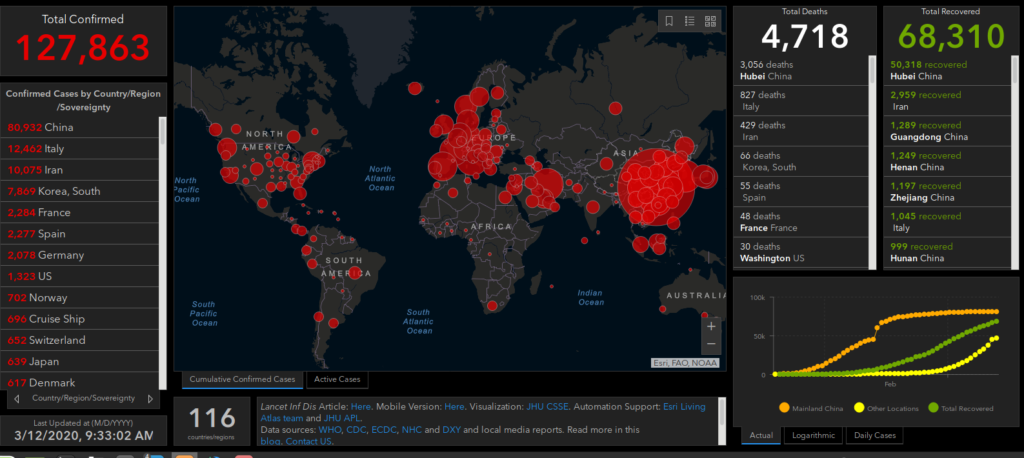

COVID-19 and planning’s contemporary relevance

In the way that the plague and jaundice epidemics played a crucial role in transforming urban planning, COVID-19 presents an opening to once again radically reconfigure urban planning. Twice over, because of the mismanaged and deadly first and second waves of COVID-19, Indian cities, peri-urban areas, and rural communities were thrown in disarray. But this chaos was exacerbated—not manufactured—as COVID-19 highlighted the broken logics of urban planning in India. Despite a nationwide lockdown that went into effect in March 2020, the enforcement of zoning laws continued unabated, further disregarding and marginalizing the lives of the urban poor. In April 2020, thousands of households in Delhi were demolished with some clusters even experiencing multiple rounds of eviction. Ironically, at the same time, the Delhi government was distributing ration and other necessities to offset the debilitating impact of COVID-19 containment strategies. Basti residents highlighted the State’s hypocrisy in providing them with gas services, ration, and voter-identity cards which strengthen their rootedness all the while serving them with eviction notices and demolishing their homes. This deliberate murkiness in urban planning adds to the challenges of those struggling to seek shelter, especially during a pandemic that necessitates staying home.

Unlike in the Global North, where life worlds can be easily divided into ‘before’ and ‘after’ the crisis, in the Global South, the everyday reality is not that much more different than the temporary health crisis. As stated in The Pandemic, Southern Urbanisms, and Collective Life, urbanism of the Global South inherently requires a constant movement and adaptation to micro and macro shifts, such as inconsistent income flow and changing government schemes. This urbanism of endless transformation creates a chronic sense of vulnerability. It means that while the urban majority was not made newly vulnerable, the pandemic and consecutive lockdowns added to the already debilitating vulnerability. The brutality of COVID-19 itself is well-documented but the design of lockdowns misrecognized every aspect of urban life in cities of the South where most inhabitants need to navigate the hustle to arrange water, food, work, waste or childcare on a daily basis. In doing so, lockdowns worsened already existing fault lines of inequality.

Layered atop pre-existing crises, including but not limited to flooding and excessive rains on both coasts in India, mass farmer dissatisfaction over the three exploitative farm laws, and heightened caste-based discrimination, this ‘new normal’ points to a grim and urgent reality. It reminds us that the time to act radically is now. As Naomi Klein recently said, ‘there is no such thing as a singular disaster anymore—if there ever was; from Covid to climate, every disaster contains every other disaster within it.’ To challenge the ways in which planning knowledge is held, and consequently the ways in which power is exercised and against whom, is an especially critical task in contemporary times of interrelated disasters.

Transforming urban planning

The inherent failure of planning to respond to the needs of the majority, aka the urban poor, necessitates a fundamental revisioning of what planning is, who it is controlled by, and how it is understood. Over the years, attempts have been made to reform planning in India, largely fostered by political action and technical interventions of civil society organizations and resident associations seeking rights to and in the city. Higher judicial courts increasingly intervene into urban governance by condemning unannounced and forced evictions without rehabilitation plans. The emergence of new forms of public-private partnerships in urban reforms have also, in certain cases, provided access to resources such as drinkable water or services and infrastructure, to the marginalized. But while these efforts have brought planning closer to democratization, they have not succeeded in diffusing power away from the technical planner/planning agency or in challenging planning’s subordination to the laws and/or the desires of the government.

To seriously build cities in which all people have equal rights and access to the benefits and opportunities of urbanization, as stated in the New Urban Agenda, there is a need to fundamentally alter how planning is understood, taught, and leveraged. Here, Foucault’s understanding of power as multi-directional and as bottom-up as top-down, helps us rethink planning’s agenda to induce resistance in groups with limited power against the dominance of greater State power.

To this end, as Urban Fellows at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), we supported anti-eviction housing activists in Indore, Madhya Pradesh by conducting workshops on the technicalities of urban planning. Our pedagogies were designed through an active collaboration between IIHS and activists fighting against illegal and forceful eviction, slum demolition, and caste dynamics in the urban space. We did the direct work of demystifying the Master Plan by deconstructing its statutory importance and introducing the concepts of land-use and zoning to the activists. Yet, the real resistance-building happened through our pedagogical approaches that emerged from two questions: can we view activism as a legitimate form of urban practice and not just a form of reactionary political engagement? Can there be a space for communities, activists, and universities to come together to inform and direct a pedagogical practice that recognizes the agency of learners and practitioners beyond the scope of formal planning education?

These provocations help us decenter the technically trained planner, the academy that produces them, and the institutions that absorb and legitimize them. This decentering—via recognizing basti residents and housing activists’ agency and knowledge—is necessary to transform planning into the broad-based, pluralistic, and democratic process that it should be.

Our second series of workshops in Indore focused on forms of tenure, government schemes, missions, and policies to support a new generation of activists in struggling against eviction. Through this, we wanted to not only support anti-eviction activists’ participation in discussions with the government on Master Plans, but to also recognize the urban activism of anti-eviction as a distinct mode of urban practice. This was especially critical as ‘public participation, even in the best situations, cannot imply the expansion of power as long as it is subordinate to laws and/or the desire of the government.’

Power relations are not static and symmetric and therefore, my aim is not to suggest universalizing the Global South’s theorization of urban planning. But by illustrating the failures of Global North-informed planning paradigms in India, I wish to challenge the notions of an ‘inadequately’ planned Global South. At a time when the spaces we inhabit determine whether we survive a deadly virus or not, urban planning becomes a critical tool in preparing for and responding to the disasters of the present and the future. For these reasons, by centring the needs of the urban poor, legitimizing activism as a form of urban practice, and demystifying the technicalities of planning, we can transform planning into an evolving and moving discipline instead of static theory.

Apoorva Dhingra is a writer and researcher based in Delhi, India. They are interested in urbanization, ecology, and climate adaptation and are passionate about building a better world. You can reach out to them at apoorvadhingra[at]pm.me.