by Neal Rockwell

Earlier on in the pandemic there was a good deal of talk about what letter best represents the economic crisis that resulted from the COVID-19 virus. The first (and overly optimistic) suggestion was the letter V – that is to say a rapid decline of the economy followed by a rapid rebound. Other suggestions were a U (like the V, but a little more drawn out), the W (two back to back Vs) and an L (steep drop off, slow recovery).

None of these seemed, however, to accurately explain what was going on, so finally pundits and commentators introduced the idea of the K shaped recovery. This one is somewhat more difficult to understand than the others, partly because only the two diagonal strokes play into the visual metaphor, with the vertical stem being extraneous, but more importantly because it stretches the meaning of the word recovery itself.

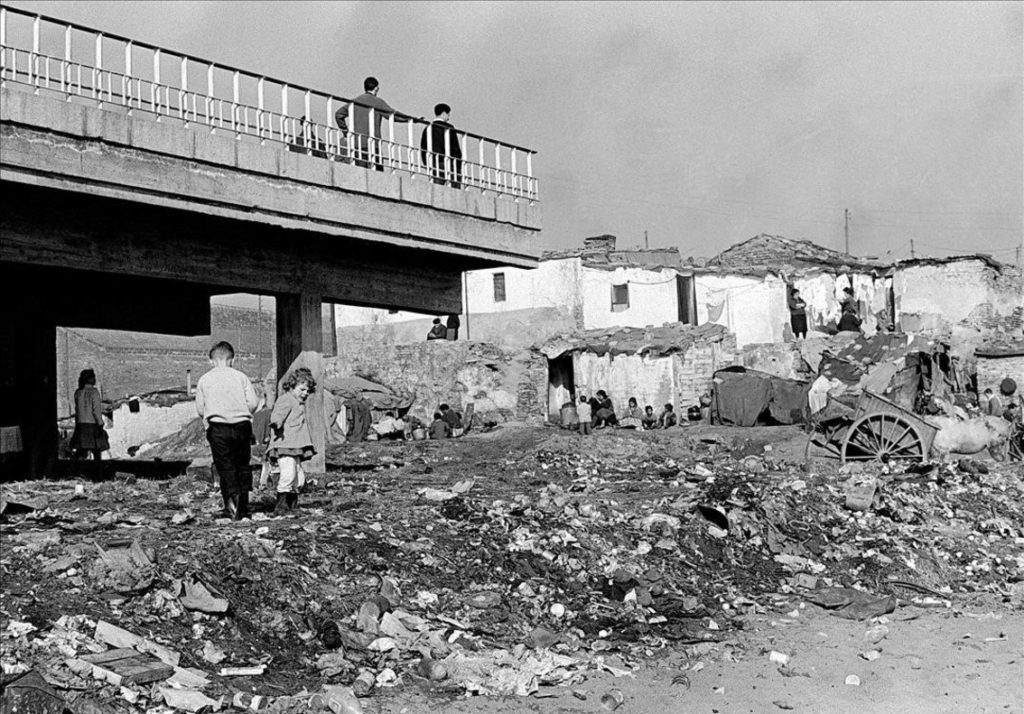

Essentially, it divides the economy into two portions, one which has seen its fortunes dramatically increased, the other which continues to slide further into poverty. For the former category there has effectively been a boom without crisis, for the latter there has been an ongoing crisis without recovery. The stock market and home prices are increasing rapidly, while many people watch their financial troubles multiply with alarming speed. It seems obvious that this should not qualify as a recovery at all, but what then is taking place?

The Asset Economy, a new monograph published by Polity Books may help shed some light on the economic structures that could provoke this unusual K-shaped economic phenomenon. This slim volume, written by three Australian sociologists, Lisa Adkins and Martijn Konigs of the University of Sydney and Melinda Cooper of the Australian National University, focuses on the way asset ownership—primarily stocks and property—has become central to our economic system, but also to the ordering of social relations within our society.

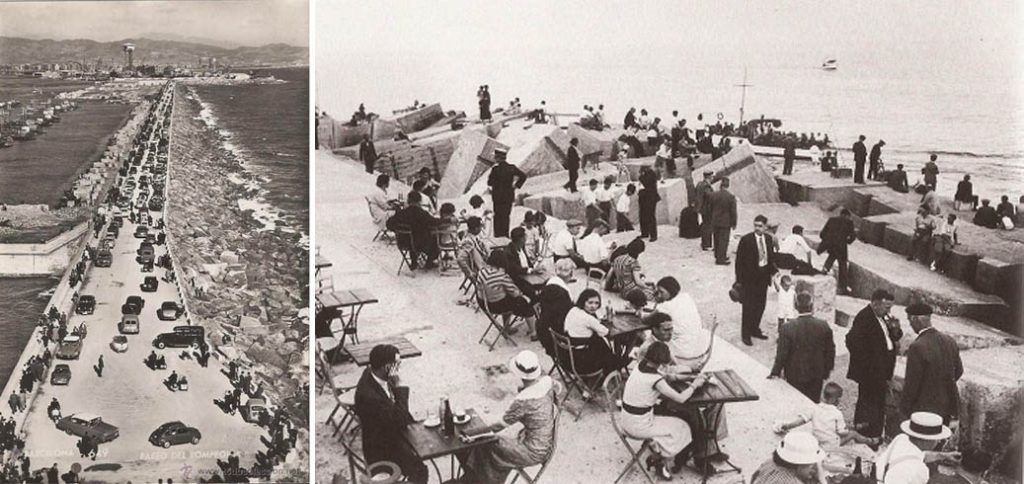

The central argument of the book is that asset price inflation (especially property) has been the main driver of wealth since about the beginning of the 1980s. As wages have stagnated, rising stock, property, and notably home equity has allowed net worth to increase, at least for those who have access to asset ownership. That idea by itself is not novel, nor even controversial. Since the election of Margaret Thatcher all governments in the English-speaking world (and many others) have pursued this policy of ‘asset based welfare’.

In essence, this is a very individualistic strategy where social welfare programs are cut, unions are broken and people’s needs are met either by owning a stock portfolio or a home whose value increases over time, providing funds for retirement as well as life’s other needs.

The downside to this welfare strategy, of course, is that it requires the constant inflation of asset prices in order to remain viable. Its value creation strategy is entirely dependent on inflating asset prices specifically in relation to the prices of consumer goods overall, and more importantly in relation to wages. That means that as time progresses this form of “welfare” becomes more and more unattainable to larger and larger numbers of people, increasing the poverty of non-asset owning people, and making cities ever more unliveable.

Class is just not the same as it used to be

What is novel about the authors’ approach is the level of detail and attention they lend to this subject. One of the authors’ main ideas is that since the 1970s there has been a shift, where the main class antagonism in society is no longer centred around employment, i.e.: between people who labour and those who own the means of production, but instead between those who own assets and those who do not. As they state “[t]he key element shaping inequality is no longer the employment relationship, but rather whether one is able to buy assets that appreciate at a faster rate than both inflation and wages.”

The main class antagonism in society is no longer centred around employment but instead between those who own assets and those who do not.

This may seem a little like Thomas Piketty’s now famous r > g (return on investments is greater than GDP growth). Piketty’s formula suggests that if return on investments is higher than growth, then investment incomes for the wealthiest are based on syphoning money from the rest of the population, more than they are grounded in actual new wealth creation. This necessitates widening income inequality.

The authors explain, however, that Piketty tends to focus mainly on the very top of the economic hierarchy—those most heavily invested in the stock market, whereas their asset economy is more insidiously distributed throughout the upper and middle classes. Home ownership is particularly vital for entry into the asset economy by people below the very top of the wealth spread and as such “housing has become a significant generator of inequality.” The authors therefore argue that asset ownership is the primary engine of class distinction and inequality in the 21st century.

The authors also take care to distinguish the asset economy from rentier capitalism (which they claim focuses too much on the very top) and financialization (which they think focuses too heavily on making assets liquid, when a large part of the asset economy involves taking on large amounts of debt to buy illiquid housing assets).

Rentier capitalism, for quick clarification, is the idea that as the economy becomes more monopolistic, the owning class makes more if its income from parasitically charging rents and fees for access to services, rather than producing actually valuable goods and services. A good example of this would be increasing bank service fees – they do not actually improve a customer’s experience, but act like a kind of private tax.

Financialization refers to the growing way that financial activities and speculation have come to dominate the economy since the 1970s, replacing industrial production as the central driver of capitalism. In short this means that much more energy is devoted to playing the stock market, and loan markets in relation to investing in producing and selling products. A good example of this is how in the last ten years companies have invested profits into buying back their own stocks to drive up their prices, rather than investing in other more concrete, productive aspects of their businesses.

The authors also downplay the worker / boss relationship in relation to contemporary capitalist exploitation, in favour of the asset / no-asset dichotomy, partly because they believe the role of commodity production is now less important to the economy than long-term asset speculation, and also because class identity is now confused. There are white collar workers like journalists, magazine editors, NGO employees, etc… who are precarious and own no assets, while at the same time there are working class people who have managed to ascend on the asset-owning ladder (though they point out that this is rarer and rarer).

Inflation is sneaky

For some time I have been puzzling over the way economic and business people tend to talk about inflation. Analysts and commentators frequently explain that we live in a period of very low inflation.

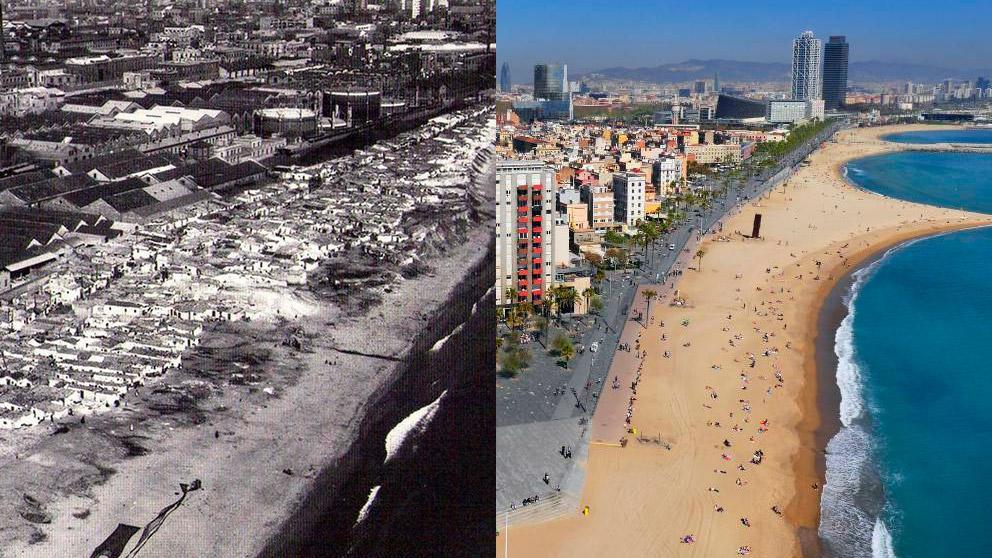

This has always seemed somewhat absurd to me because the biggest expense in almost everyone’s life—the cost of housing—has seen prices skyrocket stratospherically in the past several decades. The authors make the same observation, noting that asset price inflation should today be considered part of inflation. As they state:

[T]he official story is that we live in a world without inflation… But this obscures the fact that inflation elsewhere has been central to the making of the neoliberal asset economy. Of course, we tend not to think of asset price inflation as inflation, but that is itself the product of a particular historical conjuncture and discursive configuration. It is therefore important to understand the transition from the Keynesian to the neoliberal era as a shift from price inflation towards asset inflation.

The authors observe that in the 1970s there was an opposite dynamic at play: wage and price inflation was high and asset prices were stagnating. As they explain “[t]he wage and consumer price spiral of the 1970s was the symptom of an undecided struggle between different social groups who sought to maintain their respective shares of the national income.”

What is most illuminating here is the idea that inflation is not simply a blunt process which either is or is not happening. On the contrary, as the authors show, it is a strategic battle between different actors in society. Different types of inflation benefit different portions of the population. Inflating asset prices is an indirect form of appropriation from those who do not hold assets because it erodes the value of their earnings, while increasing the value of asset owners’ holdings.

Inflation is not simply a blunt process which either is or is not happening, but a strategic battle between different actors in society. Different types of inflation benefit different portions of the population.

In a crude sense this inflationary process is like printing money out of nothing. While overall it diminishes the value of everybody’s individual dollars it transfers a greater and greater portion of those dollars into the hands of the asset owning minority. The value that asset holders create for themselves outpaces whatever debasement of buying power this process may engender.

The authors of the book are therefore at pains to show how asset wealth is different in character from other kinds of wealth. Key to this insight is the fact that assets don’t produce goods and services or surplus themselves. Rather, when the value of assets experience inflation, those who own assets are able to capitalise on them, while those who don’t see their buying power eroded.

It’s in this sense that finance, banking, and the asset economy are actually part of a privatized system for creating money. This affords the asset-owning minority a greater and greater ability to leverage this ‘money creation’ power over the structure and direction of the real economy—the actions people perform and things people make, that are the actual measure of wealth. People who hold assets then have a unique kind of power over others, because they are able to capitalise on this specific form of inflation (which is at odds with traditional wage and price inflation), while the rest of the population is excluded from the means for a stable and secure future. The book is extremely useful in clarifying this dynamic.

Overstating assets

One of the weaker aspects of the book is to perhaps overstate the role of what the authors term the asset economy somewhat to the exclusion of the other frames that they outline their position against: rentier capitalism, financialization, and labour relations.

To take one example, one of the major drivers of financialization is cheap debt. Loading up on low interest loans is one of the drivers of asset price inflation as the authors observe, but it also allows real estate to arguably become much more liquid. These loans help make ever more expensive housing accessible to investors, fast growing equity makes it easy to sell these properties quickly and painlessly. Stories of condos being sold multiple times before they are even built are a testament to this process.

I would argue, somewhat against the assertions of the authors, that the asset economy is financialization. They are both part of a privatized money creation scheme (money is created in the form of cheap loans, inflating property prices, stocks, etc…), that shifts a greater and greater portion of the money (or if you prefer value) supply into the hands of a select few.

This is maybe an argument for a basic income of some sort—not that it would not create inflation, in the long term it likely would—but that it would increase inflation in the right direction, away from the hands of the private money creation industry and into the pockets of poor and working people. Since asset inflation, banking and finance are part of a privatized system of money creation—one that benefits mainly the people who own and control it, state monetary policy can act as a counterweight to this process. Similar to the question surrounding inflation, the issue at stake around money creation is not simply how much is too much, but who has the right to do it and for the benefit of whom? At any rate there is certainly more to consider in how these processes relate to contemporary class struggles.

Work relationships, assets, finance, rentier capitalism and other dynamics, I believe, all exist concurrently in a way that is somewhat more complicated than the vision laid out in this book. That said, the asset economy frame outlined by the authors is nonetheless very timely and does provide necessary clarification that gets missed from some of these other more widely discussed analyses.

Understating production

This leads me to what I think is perhaps a bigger weakness in The Asset Economy: understating the role of production. The authors quite correctly observe that there is no “natural” way to measure prices—markets are contingent, arbitrary, socially constructed objects. They assert that inequality in society “works less and less through extraction and appropriation, and increasingly through the inflation and deflation of temporally situated claims.”

This single sentence manages to capture both what I consider the strongest and weakest elements of the book’s argument. Personally I would not set these two dynamics against each other. I would state, to the contrary, that it is inflation and deflation of specific forms of value that drive extraction and appropriation in the 21st century.

People doing and making things is still the basis of everything we consider valuable. The asset economy, like finance, has not supplanted real wealth. What it does is reorder cash distributions across different populations.

Further, some confusion arises from the way that the authors downplay the real economy and labour. People doing and making things is still the basis of everything we consider valuable. The asset economy, like finance, has not supplanted real wealth. What it does is reorder cash distributions across different populations.

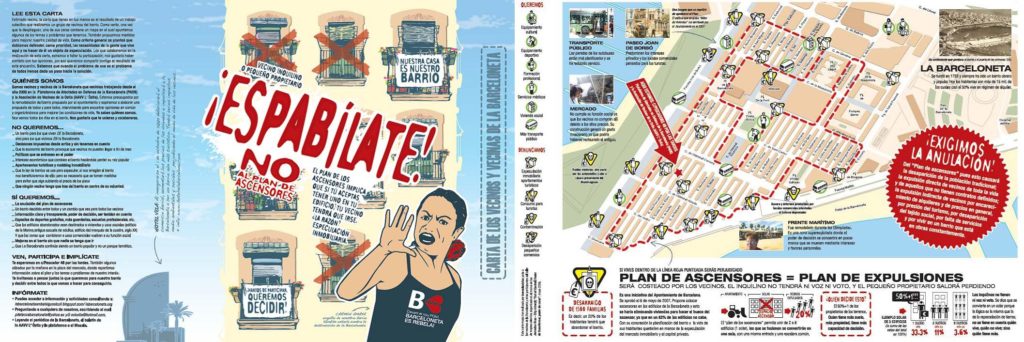

Organizing against the K-shaped recovery

Recently, housing has grown as a novel site for working class struggles—above and beyond traditional sites like factories or other workplaces. Since the pandemic, we have seen the building of tenants’ unions and neighbourhood groups organizing against evictions and rent increases. These groups themselves explicitly identify housing as a target of working class organizing. This is partly because the precarious, gig and service economies make workplace organizing more challenging versus, say, organizing a centralized factory, but also because rents and housing costs have become a main point of extraction of working people’s wealth. It is a major point of 21st century exploitation.

This is a testament to the authors’ claim that neoliberalism has reordered traditional class relations. In the neighbourhood where I live, for example, many of the buildings where organizing is taking place are owned by asset management companies. This is not incidental, and it is part of why COVID-19 has been a crisis for some and a boon for others.

It may be worthwhile at this juncture to reiterate that a K-shaped recovery is no recovery at all. The image simply highlights the widening gulf of inequality between people who own assets and those who do not. We could think of the present-day wave of organizing around housing and rent as being a direct challenge to the inequality being wrought by asset price inflation.

A K-shaped recovery is no recovery at all. The image simply highlights the widening gulf of inequality between people who own assets and those who do not.

This transformation in class identity warrants greater consideration. At the same time, we must be cautious not to overstate this conversion. It’s true that there is significant overlap between people who own assets and own businesses where people work. On the other hand, many non-asset owning people are also low-paid workers. While asset prices have reorganised monetary value and who controls it, the work done by people is still the backbone of our collective wealth.

This book offers an important and timely analytical lens by which we can better theorize the growth of contemporary inequality and exploitation. There is a good deal more work to be done. I think the answer lies not in setting asset price inflation against a labour theory of value and exploitation, but in exploring how these dynamics intersect and work together, which will give us, amongst other things, a deeper understanding of why housing has become so central to 21st century working class struggle.

Neal Rockwell is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He is currently completing a masters’ degree in Documentary Media at Ryerson University where he is exploring the effects of financialization on rental housing, as well researching the use of documentary power in the economy and the law, with the goal of strengthening documentary practice as a form of radical truth-telling.