by Winne van Woerden

“We need to foster sources of economic growth consistent with resilient ecosystems.”

“We need to decouple economic growth from resource use.”

In the midst of heated conversation about the ecological crisis, there always seems to be someone making these kinds of points. This is ‘green growth’ thinking. It is promoted by leading multilateral organisations and is assumed in national and international policymaking, including the European Green Deal, IPCC reports, the Paris Agreement and most recently in the US’ Inflation Reduction Act. You are also likely to come across green growth in your private quarrels; for many, it has become common sense.

The green growth perspective holds that we need to tackle the ecological crisis and strive towards a circular economy, while growing our economies at the same time. As such, green growth is rooted in an ‘ecomodernist’ belief in technological progress: there are no limits to growth since there are no limits to human ingenuity.

In this article, I will provide an overview of why green growth is dangerously misguided. First, the foundation of green growth is a concept of “decoupling” which doesn’t stand up to scrutiny once we unpack it. Second, capitalism’s requirement for constant growth means that any efficiency gains derived from new “greener” processes, resources or products are largely folded back into increased consumption – a process known as the Jevons paradox. Third, green growthers reason with a ‘carbon tunnel’, leading them to give reductionistic solutions to environmental issues that demand holistic ones.

Net zero and decoupling: A language to gamble with the future

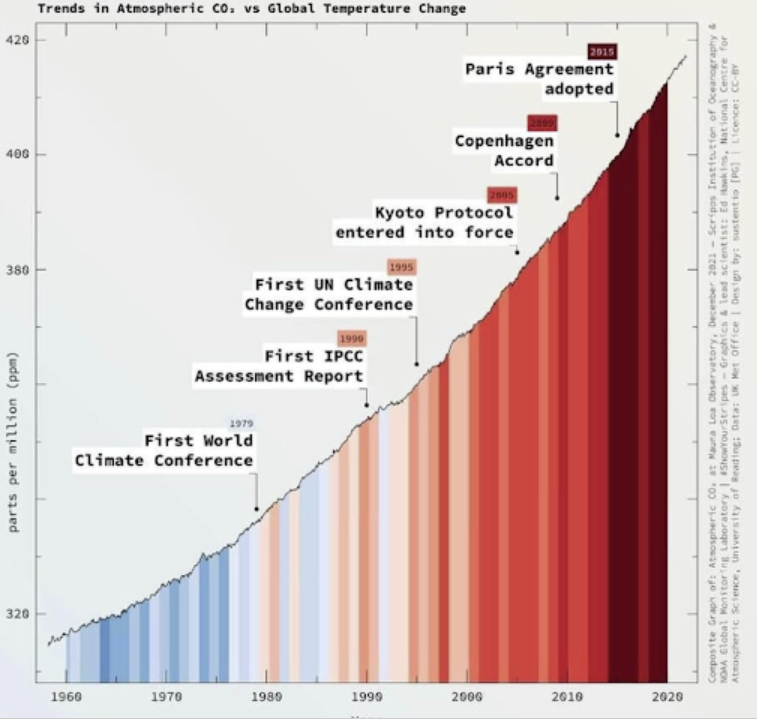

First, let’s start with some facts: at present, seven years after the Paris Agreement was made to keep global temperatures below 1.5 degrees, CO2 emissions are still rising. As a matter of fact, during the 30 years since governments gathered in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – the document that would form the basis for all future climate negotiations -more carbon has been emitted into the atmosphere than in all of history combined. The Global Energy Report of the International Energy Alliance showed that energy-related CO2 emissions grew 36.3 Gt in 2021, a record high.

To put this in perspective: the remaining 1.5°C carbon budget – the total amount of carbon dioxide that can still be emitted into the atmosphere while keeping global temperature below 1.5 degrees – was estimated to be 495 Gt CO2 at the beginning of 2020. With emissions rising at 2021 levels, the carbon budget is expected to be overshot in about a decade.

Source: Timothy Parrique ‘40 years of Bla Bla Bla’. The graph is a combination of the warming stripes of Prof. Ed Hawkins, final editor IPCC Report 2022 and the CO2 concentration ‘Keeling curve’ of the measuring station Mauna Loa in Hawaii

It is widely acknowledged that current fossil fuel investment plans of countries across the world significantly overshoot this carbon budget, even though these same governments signed the Paris Agreement back in 2015. How can this be?

Ever since 1992 there has been a faith that these overshot emissions will be offset by strategies elsewhere that sequester carbon — cap and trade, offset markets, all were efforts to envision “decoupling” emissions from their negative effects to justify overshoot. Today, the most common iteration of this is using the language of “net zero”.

“Net zero” refers to a scenario where continued emissions are balanced out with massive withdrawals of carbon from the atmosphere. Rather than aiming for actual emissions reductions, governments accept that the carbon budget will be overshot, by expecting that this ‘excess carbon’ will be pulled out of the atmosphere somewhere in the future.

Models that form the base of the Paris Agreement and scenarios assessed in IPCC reports assume carbon dioxide removal to the scale of 100 to 1000 billion tonnes of CO2 until 2100, predominantly through a set of technological solutions known as bioenergy and carbon capture and storage, or BECCS.

The idea is that through BECCS, high consumption and production levels can be maintained, while simultaneously reducing the net amount of carbon that is released into the atmosphere. Since more consumption and production means more growth of a country’s Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, it would mean that GDP growth becomes decoupled from an economy’s environmental impact. In the words of the European Environmental Agency: “The idea that societies can decouple GDP growth from environmental pressures is central to the concepts of ‘green growth’ and ‘the green economy’”. Decoupling is the panacea for how growth supposedly becomes green.

Unfortunately, this faith in decoupling has no empirical grounding. First of all, there is a need to be clear about the difference between relative and absolute decoupling. Relative decoupling refers to a situation where emissions are still rising as the economy grows, only to a lesser extent (the slope of the still rising curve has flattened a bit). Absolute decoupling refers to a situation where total emissions decrease, while the economy continues to grow. At present, we are seeing that many rich nations are in a situation of relative decoupling, while global emissions are still rising.

This leads to an important point: we must be mindful of the ways that relative decoupling is influenced by the geographical disjuncture between where production takes place and where GDP is measured. Most rich countries in the global North have outsourced their production process to fuel their energy and resource use to poor countries in the South. Furthermore, relative decoupling is often the consequence of major, one-off changes – the ‘low hanging fruits of the transition’ – such as the substitution of coal with natural gas (And too often, that coal isn’t left in the ground, but just finds other markets to be burned in). It is much harder to sustain this declining rate of emissions once this phase is over, especially in a scenario where energy demand continues to grow. Besides, relative decoupling in the global North can lead to a situation where fossil fuel infrastructures (commonly) located in the global South become ‘stranded assets’, leading (commonly) Northern corporations to divest and leave. As there is often no case of corporations remediating their toxic legacies before leaving, environmental justice groups are holding fossil fuel investors accountable for their decades of social and ecological destruction.

Reducing emissions only is not enough

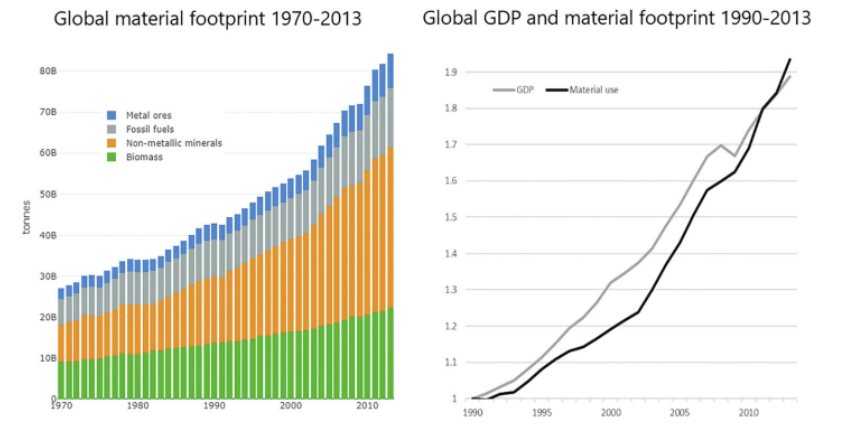

Decoupling discussions tend to focus on carbon emissions linked to our energy use, or ‘decarbonization’. However, when talking about the impact the global economy has on our planet’s ecology, we also need to talk about decoupling our economy’s broader material footprint or ‘dematerialization’. While absolute decoupling of emissions is happening in some regions, there are almost no cases of the absolute decoupling of resource use.

In 2020, a team of researchers performed an extensive systematic review looking into 835 peer-reviewed articles and found that there is no empirical evidence of absolute decoupling of emissions at a regional or global level. Moreover, modelled projections indicate that with existing growth trajectories, this is unlikely to be achieved. GDP growth remains significantly coupled with carbon emissions.

At the national level, there are some cases of absolute decoupling. A study often cited to defend green growth and empirically prove decoupling shows that between 2005 and 2015, 18 countries (Sweden, Romania, France, Ireland, Spain, UK, Bulgaria, The Netherlands, Italy, United States, Germany, Denmark, Portugal, Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Finland, and Croatia) have decreased their CO2 emissions by 2.4% per year. This is good news, but unfortunately, it is only one third of the reductions in emissions that are needed at a global level to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. Moreover, part of that decrease can be explained by a slowdown in GDP growth rates of the countries where absolute decoupling was observed.

As for resource use, empirical records demonstrate a similarly strong relationship between GDP and material footprint. Towards the end of the twentieth century GDP grew at a faster rate (3 percent per year) than resource use (2 percent per year), which represents a small relative ‘decoupling’. But this changed in the 21th century, when the growth rate of global consumption accelerated and so did global resource use, to 3.85 percent per year, a bigger increase than GDP in the same period, meaning that the material intensity of the global economy has in fact increased during that period. As the authors of one of the most extensive studies looking into this put it: ‘Currently, the world economy is on a path of re-materialization and far away from any – even relative – decoupling.’ Meanwhile, modelled scenarios show that under growth-as-usual conditions absolute reductions in resource use are unlikely to be achieved at a global level even with dramatic efficiency improvements.

Source: Materialflows.net/World Bank

As the authors of the report “Decoupling Debunked” of the European Environmental Bureau put it: “Of all the studies reviewed, we have found no trace that would warrant the hopes currently invested into the decoupling strategy”.

The scientific community is beginning to see that the huge reliance of global climate mitigation strategies on green growth thinking is speculative and risky.

Of course, the fact that decoupling hasn’t worked historically does not mean that the future can’t be different. But the question is not only whether it will be technologically feasible to achieve absolute decoupling; the question is whether we can reduce emissions fast enough to stay below 1.5 degrees warming, while still continuing economic growth. Given the remaining planetary carbon budget, we don’t have the time to afford ourselves a ‘technological challenge’ like this. We need to make it as easy as possible to make the energy transition in the fastest possible way, and economic growth, which continues to be coupled with emissions and material footprint, does not appear to be helping. Paradoxically, while it is common for people in the green growth camp to raise the notion of speed, it is exactly those who continue to defend growth who don’t have time on their side.

The efficiency paradox

When you confront a hardcore green growther with these facts, you will hear a reply like “Just wait for it, we are seeing such huge improvements in the technologies that will make our economies green. Just look at how efficient solar panels are today compared to just a few years ago!”

With arguments like this, green growthers confuse efficiency with scale. In growth-dependent economies, the more efficiently we use resources (like those needed to set up a renewable energy infrastructure) the lower they cost, and the more of them we end up using. This rebound effect is known as the ‘Jevons paradox’: increases in efficiency in the use of a resource lead to an overall increase in the use of that resource, not a decrease.. Why? Because under capitalism, growth-oriented companies use the savings to ramp up production and stimulate consumption. As a result, the anticipated efficiency gains are squandered by increased consumption or changes in consumption behaviour. As the production of Teslas becomes more efficient and costs less, Elon Musk will simply re-invest the saved money on marketing to convince more people to buy a Tesla while seeking new profitable investment areas. At the end of the day, as more and more people are getting used to the sight of a city filling up with electric bikes and electric cars, we aren’t actually using less energy but continue to normalise energy and materially intensive products into what counts as a standard mode of living.

Some people argue that the economy might require less energy with the shift to services and digitalization observed over the past decades in many high- and middle income countries. But actually, tertiarization in industrialised countries, as well as efficiency improvements achieved through digitalization, have led to increases in energy use and CO2 emissions during the last decades. In essence, any economic growth is anchored in a materialized economy, despite the imaginary of a dematerialized knowledge economy.

This continued growth in energy demand results in a situation where the introduction of new energy sources – like solar and wind – aren’t replacing older sources of energy, but are complimenting them. This turns what is supposed to be an energy transition in theory into an energy expansion in practice. As Jason Hickel has put it: ‘trying to fill an ever growing energy demand with clean energy sources makes the energy transition only more difficult in the short time we have left’.

All of this is not to say that post-growth voices that criticise green growth thinking are against technological innovation. Substituting fossil fuels by cleaner forms of energy is imperative. But scaling up green technology is simply not enough. Instead of struggling to “green” expanding economies, we also need a planned, absolute reduction of energy and resource use in high-income nations. It is exactly this reduction that the political and corporate elite who continue to defend green growth hate to think about, since it is exactly their lifestyle that ends up being the most energy and resource intensive.

The carbon tunnel

Picture a green growth future. Rich countries will have electrified their total energy supply system by 2050. Renewable energy infrastructures are upscaled massively (IPCC models assume an expansion during the upcoming decades with a factor 40-50). Clean energy sources are being used very efficiently: “everybody” has an electric car, an electric bike, solar panels on their roof and a heat pump in their basement. Growth has become clean and no need to think about ecological limits whatsoever.

Besides the fact that such a scenario glosses over questions of power and ownership and obscures mounting inequities within rich countries in people’s access to the goods and services to meet their basic needs (whether provided in a green way or not), it also reveals a simple, almost childish fact: we can’t have unlimited growth on a limited planet.

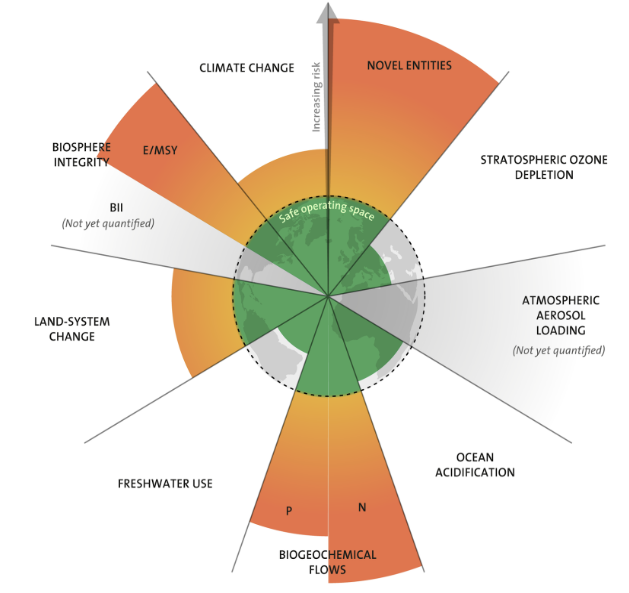

Damming rivers, erecting wind turbines, and installing solar energy fields to supplant fossil fuels still requires enormous amounts of raw materials and still leads to the wrecking of ecosystems – systems that particularly people in the global South depend upon for their survival. Scaling BECCS to the level assumed under the Paris Agreement requires massive amounts of agricultural land (equivalent to two times the size of India) and water for biofuels. This raises profound questions about land and water availability, competition with food production, emissions from land-use change, water depletion,biodiversity loss and ultimately Earth’s ability to nurture human and non-human life. In essence, by focusing solely on reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere through technological innovation, green growth thinking looks at only one planetary boundary. However, Earth scientists show us that it is more useful to consider the nine natural systems that interact in a complex way to enable life on Earth. These interactions explain the occurrence of ‘climate tipping points’, referring to how a certain change in one natural system could abruptly trigger an irreversible cascade of ecological destructive events through structurally changing the way the Earth’s system functions. The fact that many IPCC scenarios relying on BECCS assume a temporal overshoot of 1,5 degrees warming, risks hitting these irreversible tipping points during that overshoot period, leading to the sudden release of greenhouse gases captured by ecosystems functioning as ‘carbon sinks’, like oceans, forests or permafrost areas.

Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre

All of this reveals the need for holistic climate mitigation policies that acknowledge the basic principle of ecology: everything is interconnected. The fact that green growth thinking fails to see this, shows the reductinstim and short-termism of it. In essence, green growth thinkers reason from within a ‘carbon tunnel’.

Growth has always been a colonial project, so is green growth

Finally, we shouldn’t forget that growth has always been a colonial project. We know that resource use in the Global North is in large part appropriated from the Global South, through what are effectively patterns of imperial power. A paper published this year indicated that the value of appropriated resources from South to the North over the period 1990-2015 totaled $242 trillion in terms of prevailing market prices. This drain of Southern resources, equivalent to a quarter of Northern GDP, outstripped their total aid receipts by a factor of 30. In 2015, the North appropriated from the South 12 billion tons of embodied raw material equivalents, 822 million hectares of embodied land, 21 exajoules of embodied energy, and 188 million person-years of embodied labour. These resources could be mobilised to meet domestic needs directly and to fight extreme poverty in the Global South, rather than being used to service growth in the Global North. In fact, the authors who revealed these numbers calculated that this appropriation was worth $10.8 trillion in Northern prices, which would be enough to end extreme poverty 70 times over.

The green growth framework replicates this colonial thinking and applies it into the energy transition. Already, the demand for rare earth materials to massively build wind turbines and solar panels in the global North is increasing the pressure on resource rich areas overwhelmingly inhabited by Indigenous and marginalised communities in the Global South. Meanwhile, we know that people living in the South have contributed least to the current distorted state of Earth while bearing the biggest share of the burden of environmental breakdown. A green transition coupled with maintaining growth in the North will inevitably increase the destruction of their livelihoods, transforming them into ‘green sacrifice zones’.

To conclude: Capitalism’s growth logic is in direct opposition to making a just transition to a genuinely sustainable world economy as fast as possible. Putting negative-emission technologies and the green growth belief at the basis of the global climate mitigation agenda is an unjust and high-stakes gamble and is not an ecologically coherent approach to the crisis we face. In acknowledgement of this, an increasing number of scientists are calling for a post-growth climate mitigation agenda that is aligned with how our planet’s natural systems work and that is grounded in empirical reality. Only then can we truly speak about a just transition to a sustainable economy.

Winne van Woerden works as Lead Degrowth & Caring Economy at Commons Network, an Amsterdam-based think-thank for the social and ecological transition. She holds an MSc in Global Health from the University of Maastricht and is a master’s candidate in Degrowth: Policy, Economy and Ecology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. She is the lead author of the book Living Well on a Finite Planet, Building a Caring World beyond Growth.