by Diana Vela Almeida

La versión en español de este artículo está disponible aquí.

One could simply define extractivism as a productive process where natural resources are removed from the land or the underground and then put up for sale as commodities on the global market. But defining extractivism is not really this easy. Extractivism is related to existing geopolitical, economic and social relations produced throughout history. It is an economic model of development that transnational companies and states practice worldwide and that can be traced back more than 500 years all the way to the European colonial expansion. You can’t tell the history of the colonies without talking about the looting of minerals, metals, and other high-value resources in Latin America, Africa, and Asia—looting that first nourished demands for development from the European crowns and later from the United States, and more recently also from China.

Today this model of accumulation of wealth remains a key part of the structure of a globally dominant capitalistic system—a system where power is in the hands of those who control money and industry—that has extended the extractive frontier to the detriment of other forms of land and resource uses. Such exploitation has also appropriated human bodies in the form of slaves or, more recently, as labor-intensive precarious workers. Extractivism is entirely tied up with exploitation of people.

Today’s extractive industries such as gas, oil, and mining have an egregious reputation of violating human and environmental rights and supporting highly controversial political and economic reforms in poor countries.

Expanding the global frontiers of extraction

Since the mid-20th century, extractive frontiers have expanded around the planet as global demand for commodities has increased. Most non-industrialized countries (but also industrialized countries such as Norway, Canada, and the US) have activated their primary sectors of production to exploit landscapes that were previously inaccessible, such as in the case of fracking and tar sands extraction in the Artic or in the open sea.

Since the mid-20th century, extractive frontiers have expanded around the planet as global demand for commodities has increased

The central idea behind such state-sanctioned extractivism is that extractive projects are strategic ventures for national development in resource-rich countries that can thereby strengthen their comparative economic advantages—that is, their economic power relative to the economic power of other nations. In other words, poor nations can exploit their natural resources as a means for economic growth, a source of employment, and ultimately a tool for poverty reduction.

This idea has been ingrained for many years in developing countries, and yet these countries have historically been unable to convert resource wealth into so-called development. Indeed, in some places that are rich in natural resources—typically in African countries with large oil or mineral deposits—there is an inverse relationship between poverty reduction and economic performance. This means that a lot of extractive activity is coupled with high levels of poverty, economic dependency on capital flows from developed countries, and political instability. This phenomenon is known as the “resource curse.”

In the last 20 years, several governments in Latin America, Africa, and Asia have challenged the “resource curse” by asserting national control over new forms of primary-production extractive industries. These are oriented around intensive and large-scale projects that cover previously inconceivable environments (again, like off-shore mining or fracking), as well as new forms of economic exploitation such as the agroindustry, fisheries, timber extraction, tourism, animal husbandry, and energy megaprojects.

These endeavours require national policy reforms. In Asia and Africa, extractivist national policies adhere to what is called “resource nationalism” and include the total or partial nationalization of extractive industries, renegotiation of contracts with foreign investment, increased public shareholding, new or higher taxation to expand resource rent, and value-added processing of resources.

In Latin America, the commodity boom at the beginning of the 2000s, marked by the increase in commodity prices together with transnational investments, led to great economic growth in what is called “neoextractivism”. Neoextractivism is a relative of resource nationalism and its emergence coincided with the rise to power of several progressive governments in the region that also seized more state control over natural resources within their national boundaries.

Advocates of neoextractivism claimed that new extractive practices would be “environmentally friendly” and “socially responsible”, thereby minimizing the disastrous impacts of extractivism as it was practiced throughout colonial and neoliberal history. Despite this, extractive industries have expanded and continue to expand in new frontiers with the negative effects of dispossessing people from their land, subjugating communal values to the values of extraction-driven development, and disrupting social structures, territories, and alternative forms of life.

In the debate over extractivism, there is no consensus about how to solve the problems caused by this mode of development. Some people think that extractivism should be viewed positively because of the economic growth and increased public spending that was accomplished during the early 2000s in Latin America. Others emphasise that most of the wealth produced is siphoned out of the producer countries to transnational investors, while negative impacts remain locally or regionally. And from the perspective of those who are directly affected by extractive industries, it is clear that economic revenues are not translated into socially just well-being and that these revenues are generated through the destruction of their lives and their land.

Not a neutral economic model

To further understand the complexity of the problem with extractivism, let us look at three interrelated dimensions of what makes up the extractivist economic model—and then consider how to go beyond the economic considerations of extractivism.

First, for extractivism to work, any biophysical “nature” becomes exclusively framed as a natural resource. That is, nature is conceived as an input (e.g. a resource like oil, soil, or trees) for the production of a commodity (e.g. gas, food, or timber). This simplifies the multiplicity of socionature relations with which such an economic model is entangled.

When thinking about the environmental impacts of extraction, we surely need to consider what will happen to other elements in nature that are interconnected with the extracted resource, including water, air, soil, plants, and human and non-human animals. A cascading effect of environmental change indeed often occurs in ecosystems that are impacted by extraction, and thus interrelated elements of nature become irreversibly altered.

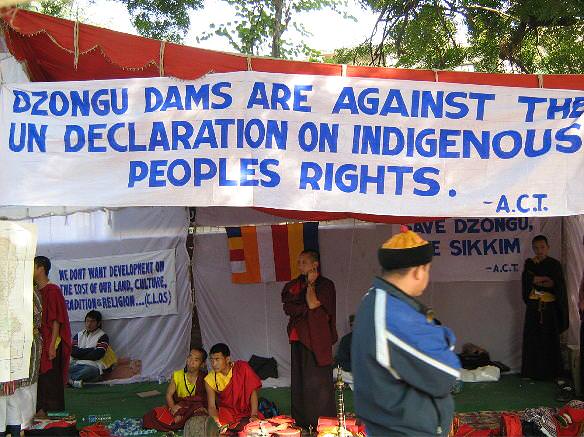

Second, extractive projects are normally located in or close to marginal, poor, and racialized (i.e. conceived as non-white) populations. Extractivism arrives with promises of improved life conditions, more jobs, and infrastructure development. But large-scale extractive industries are by no means necessarily interested in forwarding local employment and improving the livelihood of people. Instead, experience tells us that they often serve to diminish alternative economic activities and disrupt existing community networks and social structures. Extractive industries have frequently dispossessed people of land rights with the result of cultural disruption and violence.

Demands for social and environmental justice revolve around claims that the social and environmental costs of extractivism are higher than any economic benefit

Marginal populations still bear the brunt of the social costs of extractivism and don’t necessarily reap any benefits. In response to this, demands for social and environmental justice revolve around claims that the social and environmental costs of extractivism are higher than any economic benefit but that these costs are not accounted for in the decisions.

New demands from feminist movements and women Indigenous defenders highlight the relation between extractivism and patriarchal and racial violence and how this disproportionately impacts women. Examples are the increase in prostitution and sexual violence in communities restructured by extractivism and the externalization the social costs—the transfer of responsibilities for caring that are pivotal for the functioning of any economy—to women. As women are primarily responsible for the reproduction of life, they are highly vulnerable to the rupture of community or loss of territory. Because of that, women organizations have become the frontline defenders of their territories in the resistance against extractivism.

Finally, extractivism is a highly political endeavour that maintains a model of capital accumulation and destruction. It has led to the increase of socio-environmental conflicts around the globe, involving measures by states and industry to control resistance and criminalize social protest.

So, in sum, one should define extractivism as far from neutral or apolitical; it is an economic model that reflects a specific political position that relies on a given, predefined understanding of growth-oriented development as the ultimate good. Extractivism thereby reinforces political-economic arrangements that are biased against marginalized people who are deprived of their power to influence political decisions.

From an extractivist political perspective, resistance against extractivism is naïve, obstinate NIMBYism (Not in My Backyard-ism), or ignorant of the economic needs of the countries that could be “developed” by extractive projects. In reality, actions of resistance are contestations that challenge the dominant extractivist worldview and the uneven power relations between actors who decide, actors who benefit, and actors who bear the negative consequences of extraction. Under these conditions, extractivism is in complete contradiction to social and environmental justice and care for nature and life itself.

All in all, extractivism as a single model of production remains one of the most expansionist global enterprises and it squashes any other ways of living with the land. The 500 years’ legacy of extractivism is part of ongoing imperialist interest from industrial powers in securing access and control over natural resources around the globe, even in today´s green energy transitions. As such, extractivism stands in sharp contrast to flourishing alternative forms of land use and livelihoods.

Opposition to extractivism does not mean that people can’t use a resource at all and by no means implies a binary choice between either extractivism or underdevelopment. Instead, anti-extractivism is about focusing on what type of life we want to achieve as a whole and how we build global systems of justice. We can nourish ourselves from several non-extractivist modes of production and reproduction that center on a dignified life for all.

Further resources

Bond, P. (2017). Uneven development and resource extractivism in Africa. In Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics (pp. 404-413). Routledge.

This article explains the expansion of neoliberal environmentalism in the extraction of non-renewable natural resources in Africa. The author argues that if accounting the social and environmental costs, African countries end up poorer than before extraction.

Burchardt, H. J., & Dietz, K. (2014). (Neo-) extractivism–a new challenge for development theory from Latin America. Third World Quarterly, 35(3), 468-486.

An overview of key debates of ‘Neo-extractivism’ and the role of the state in Latin America.

Engels, B., & Dietz, K. (Eds.). (2017). Contested extractivism, society and the state: Struggles over mining and land. Palgrave Macmillan.

A presentation of several case studies around the globe on the conflicts between extractivism and other land uses.

Galeano, E. (1997). Open veins of Latin America: Five centuries of the pillage of a continent. NYU Press.

A classic essay on the history of the looting of natural resources, colonialism and uneven development in Latin America from the 15th century to the 20th century.

Svampa, M. (2015). Commodities consensus: Neoextractivism and enclosure of the commons in Latin America. South Atlantic Quarterly, 114(1), 65-82.

A critical analysis of neo-extractivism, capital accumulation, environmental conflicts and development. It ends up discussing proposals around ideas of post-extractivism and transitions.

Diana Vela Almeida is a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Geography at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Diana combines political ecology, ecological economics and feminist critical geography to study extractivism, neoliberal environmentalism and socio-environmental resistance. Contact: diana.velaalmeida[at]ntnu.no