by Geoff Garver

Green New Deal? People, we have a problem.

You go into your Wall Street investment bank and ask, “What’s a hot investment these days?” Your super sharp investment advisor says, “Farmland in Africa! People have to eat, right? And there are more and more people. Put your money in African farmland and you’ll double your money in no time!” She doesn’t say a word about what makes that land unique and special or about the people and other beings that live, or lived, there.

That’s a big problem. It’s a remote ownership problem. In fact, it’s a whole bunch of justice problems related to the hard-wired legacies of colonialism that come together as a multi-faceted problem about remote ownership of land and resources. In a nutshell, remote owners or rights holders often cause serious harm to far away ecosystems they know and care little about, and grave injustice to the people and other life that know those ecosystems most intimately and depend on them.

So, what about this Green New Deal (GND)? Is it merely the old wine of capitalist growth-driven development in a new bottle, or is it a recipe for socio-political and socio-ecological transformation that will right past wrongs and reshuffle political power in favor of historically disempowered people? Any Green New Deal (GND) framed as a “just transition” has to address problems of remote ownership and empower place-based governance.

Open questions about the remote ownership problem in AOC’s GND

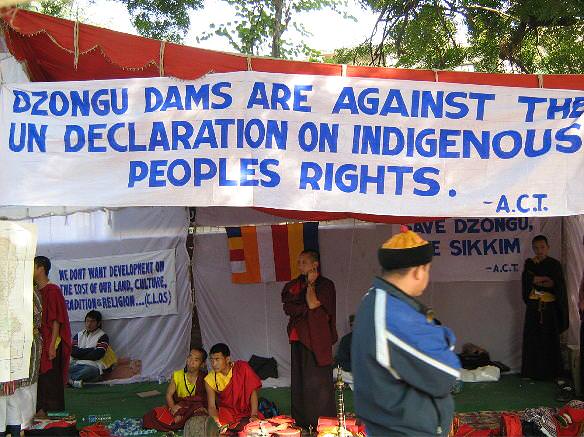

Some say the GND in H.R. 109 introduced by Rep. Ocasio-Cortez and others is merely a shift to green or climate colonialism, by which the greening—via decarbonization and other means—of wealthy, developed countries in a growth-driven, capitalist, and globalized world will worsen injustice in developing countries. This injustice includes not only increased exposure to environmental harms and health risks from extraction of materials needed for green technologies but also ongoing wealth inequality and social and cultural upheaval as the wealth-building potential of extracted resources (jobs, profits, etc.) is mostly exported along with them.

The GND risks continuation of the crushing of long-standing place-based governance systems.

At the heart of this injustice are international companies and their stockholders and other remote owners—land and resource grabbers—that exert enormous political power from the local to the global scale. The GND risks continuation of the crushing of long-standing place-based governance systems, permanent displacement of people with the most intimate knowledge of local ecosystems and devastation of ecosystems and the life they support, all typical of land and resource grabbing around the world. A particular concern is that land use reform is essential to success of the GND, yet the GND does not directly confront the hard wiring of the property rights regimes that must be addressed. Another is that the GND was conceived and announced with virtually no inclusion of Indigenous voices and that unless this lack of inclusion and the superficiality of references to Indigenous ideas is overcome, the GND could maintain “broken structures that perpetuate disconnection and individualism.”

Some cautiously, others more enthusiastically, see the GND as an opportunity to end and provide restitution for these injustices. The openings for transformative change to scale back land and resource grabbing and empower place-based governance systems, including Indigenous ones, are signaled in support for “community-driven projects and strategies” to deal with pollution and climate change; locally-appropriate ecosystem restoration; and free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous communities with respect to matters of concern to them. For these openings to fulfill their potential, justice activist Syed Hussan argues that the GND must foster “just transition in the broadest sense” and not just deal with displaced workers in fossil fuel industries and other discrete issues that decarbonizing the economy will entail.

Where to look for answers to remote ownership problems

The good news is that worthwhile ideas about how the GND can confront problems of remote ownership and promote locally-tailored place-based governance systems are already out there. Here are some of these sources of inspiration.

The degrowth movement. Degrowth is a forceful challenge to the growth-insistent sustainable development model, and a more hopeful approach to long-term perpetuation of a mutually enhancing human-Earth relationship. Degrowth combines a commitment to respecting ecologically-based limits with a commitment to developing a comprehensive, practicable approach to building thriving human communities based on conviviality and human solidarity without consumerism or material and energy excess. The reforms associated with degrowth “emphasize redistribution (of work and leisure, natural resources and wealth), social security and gradual decentralization and relocalization of the economy, as a way to reduce throughput and manage a stable adaption to a smaller economy.” Giorgos Kallis’s nine principles of degrowth should be useful in making sure the GND adequately confronts remote ownership problems: 1) End to exploitation; 2) Direct democracy; 3) Localized production; 4) Sharing and the commons; 5) Provision of relational goods, through friendship, love, healthy relationships, kinship, good citizenry; 6) Unproductive expenditures geared to communal activities, such as festivals, games and the arts; 7) Care, and treating humans and other life as ends, not means; 8) Diversity; and 9) Decommodification of land, labor and value.

The G20. What?!? Well, it’s useful to understand the key ideas of the global political apparatus that must be overcome for the GND to lead to radical social, political and ecological transformation. At annual meetings, the G20 typically agree on the need to “further collective actions toward achieving strong, sustainable and balanced growth to raise the prosperity of our people.” The means to do so generally involve supporting global trade and investment (much of which is tied to remote ownership) and the role of the World Trade Organization as a means to create jobs and maintain growth, with weak or marginal actions or aspirations to address inequalities, corruption, climate change and environmental harm. The G20 supports the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, with emphasis on sustainable, inclusive economic growth. A truly progressive GND should look past the SDGs!

The EJ Atlas. The Environmental Justice Atlas documents real cases of how remote owners have created social and environmental conflict. These compelling narratives are a rich resource for understanding in detail the problem of remote ownership and the power dynamics that must be confronted and reshuffled in order to overcome them.

Indigenous ways of thinking and being. In many Indigenous worldviews, attachment to place, founded on respect for all life and for deep appreciation of a reciprocal relationship with the Earth and its life community, is key to a more hopeful vision of the human-Earth relationship. Indigenous activist Eriel Deranger writes, “It is Indigenous communities, locally, nationally and internationally, that continue to push for an actualization of instilling deeper spiritual connections to Mother Earth to help us relearn what systems of colonization, capitalism, and extractivism have severed.” Connecting or reconnecting to the places that nourish our bodies and souls is at the heart of the long-term promise of a GND done well. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that “[f]or the sake of the peoples and the land, the urgent work of the Second Man may be to set aside the ways of the colonist and become indigenous to place.” But, inviting settler societies to become indigenous to place—and an invitation from Indigenous holders of knowledge of a place is essential—does not mean letting them “take what little is left.” Attaching to a place by carefully and respectfully seeking to become indigenous to it requires humility above all, and it requires direct experience with wise teachers, not merely book knowledge.

Indigenous peoples and other social groups that have been historically disadvantaged by colonization and land and resource grabbing must play a central role in developing and carrying out the GND.

Six mutually reinforcing proposals on remote ownership and place-based governance for the GND

First, Indigenous peoples and other social groups that have been historically disadvantaged by colonization and land and resource grabbing must play a central role in developing and carrying out the GND. Including Indigenous notions of justice, decolonization and self-determination through meaningful inclusion of Indigenous communities in decisions that affect them, which requires adequate time and resources, is essential.

Second, the GND should empower communities like those included in the EJ Atlas to develop strong place-based governance systems and communities of solidarity and mutual care in order to resist the social and environmental conflicts they face, often because of remote ownership. This means providing them with a determinative role in decisions affecting them directly and indirectly. It also means developing a global/international scope and strategy so remote ownership problems in one place aren’t just displaced elsewhere. Also, we should look for opportunities to scale up and out from local remote ownership problems that are avoided or justly resolved.

Third, the GND should end corporate giveaways that are tied to remote ownership problems and exclude carbon markets, offsets or emissions trading regimes, and geoengineering—all of which typically pose remote ownership problems. Instead, the Climate Justice Alliance is fighting for a GND that shifts “from global systems of production and consumption that are energy intensive and fossil fuel dependent to more localized systems that are sustainable, resilient and regenerative.”

Fourth, stocks and other investment instruments in land and resource grabbing ventures that cause social and environmental conflict and harm in faraway places should be prohibited. This may require profound restructuring, dismantling or abolition of the financial and corporate structures that allow for these kinds of investments. At the least, it would entail deep rethinking of the metaphor of corporate personhood

Fifth, the GND should explicitly reject economic growth as a rationale and driving objective. It should oppose perpetual economic growth and promote communities committed to solidarity, maximal sharing and minimal use of materials and energy.

Sixth, the GND should place limits on wealth, which would help minimize or end the remote ownership problem. The most obvious way to do this is through progressive income taxation or a tax on wealth. For this to be effective, there of course also has to be collaboration between communities worldwide against tax evasion, with the aim of abolishing tax havens. A more radical transformation would be to target the globalized currency system which makes it possible for Wall Street investors to buy African farmland with US dollars in the first place. Or, the international community could finally adopt taxes on financial transactions; already implemented in some countries, this could be expanded to more countries and international transactions.

Some tough questions to test these proposals

If the GND is a step toward post-capitalist societies where remote owners, if they still exist, are no longer able to adversely affect far away ecosystems and people, it nonetheless is starting off in a globalized capitalist economy. As John Bellamy Foster has written, “We have to go against the logic of the system while living within it.” Making the proposals above work will not be easy. It will require people power through mass organizing and consciousness building. And it will mean confronting some tough questions. Here are a few.

Does the GND inevitably imply ongoing wealth and resource extraction in the global South to benefit the global North? If so, what are the implications for remote ownership and place-based governance? If not, what mechanisms are needed to minimize or end wealth and resource extraction in the global South to benefit the global North?

How can the GND address remote ownership in the form of ownership of financial stocks or other financial investments—keeping in mind how many people are counting on this type of investment for their retirement and long-term care?

What are some good examples that could be duplicated or scaled up of place-based governance systems that maintain fairness among humans and between humans and other life across generations? How should duplication and scaling up account for the unique features of different places and avoid one-size-fits-all approaches?

Can the GND adequately address, as Deranger puts it, the “intertwined roles of capitalism, consumerism, militarism and colonialism as foundations to the current crisis” if it remains “driven by White ENGOs, those with the resources and power, and mainstream political parties”?

Is re-establishing traditional labor protections and increasing unionization a long-term solution, or does it risk locking in an us-them worker-owner power dynamic—where the owners are often also remote owners and land and resource grabbers—that other alternatives could overcome? What about more locally-committed, place-based employee-owned businesses or cooperatives?

Final thought

Questions like these need to be asked in relation to every single aspect of GND proposals in the advanced capitalist countries. Political organizers and activists should think about how to balance such critical questions with the visionary rhetoric that makes the GND so popular—all the while keeping in mind that the strength of a GND vision should be judged on the basis not only of its policy designs but also its ability to inspire and unite broad movement building for climate justice. Grappling with entrenched problems of remote ownership is one way to take a focused approach to building momentum for this movement.

Dr. Geoff Garver is an adjunct professor at Concordia and McGill Universities in Montreal and coordinates research on law and governance at McGill University for the Leadership for the Ecozoic initiative. He is on the steering committee of the Ecological Law and Governance Association and the board of the Quaker Institute for the Future and is active in the international degrowth movement.