by Soumik Dutta

On May 2nd, 2016, two people, including a Buddhist monk, were killed when police fired at a crowd of protestors in India’s Arunachal Pradesh state bordering China—injuring ten others. The protest was sparked by the arrest of Lama Lobsang Gyatso, a monk active against mega power projects in the Tawang district.

Anti-dam protesters in Arunachal include various student bodies, environmental groups, and civil society organisations. This January, hundreds of Buddhist lamas joined protests in Tawang, a smaller district in the province, to say no to large dams in the ecologically, culturally and strategically sensitive area. Various Indian national level media outlets reported the Tawang protests, and people’s Facebook news feeds were abuzz with the Tawang firing.

At the root of the protests are changes to India’s energy policies, said to be crucial for the country’s economic development. India’s National Hydro Power Policy of 2008 had identified a total capacity potential of 1, 48,701 MW of hydropower in the country, of which 50,328 MW was in Arunachal Pradesh alone. Of these, the 2,000 MW Lower Subansiri hydro project 80% of the construction of which has been completed has been stuck since December 2012 following massive protests in downstream Assam.

At the root of the protests are changes to India’s energy policies, said to be crucial for the country’s economic development.

The Arunachal Pradesh government has signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with various companies for over 100 big and small hydropower projects in the state, and 13 of these with a total installed capacity of 2791.90 Mega Watts (MW) are in Tawang. The abundance of rivers in the Himalayas and the nation’s ever-growing demand for power propelled the government of India to envision a national hydro power policy that would exploit the vast hydro power resources of Himalayan states like Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh.

Energy is crucial to the economic development needs of every nation. Hydro power, which was considered clean energy with very negligible impact, has however turned out to be quite the opposite. Often, projects have socio-cultural impacts on communities dependent on the river and often have disastrous environmental results. In many cases, the myth about hydropower being cleanest and safest is turning out to be untrue. Human lust for more economic development and the consequent need for more power has created a situation where water, the most abundant natural resource, has become a bane—a resource curse.

The Arunachal firing is a case in point. Many other states in India have witnessed similar protests and ruthless oppression by the government. In fact, when it comes to hydro power projects globally, a politician-corporate development nexus that results in the oppression of civil protests has become a common scenario. International organizations, politicians, investors, and developers are uniting to participate in the systematic plunder of the most abundant natural resource, water, in the garb of economic and sustainable development of nations.

Sustainable energy or environmental conflict?

Hydro power is often put forward as a clean, sustainable form of energy. In the case of India’s Himalayan states, there are both public and private benefits. Apart from the incentive of generating revenues from sale of hydro power, the certified carbon reductions (CERs) from the United Nations framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC), under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) has worked as a strong factor for both the private project developers and the government for pursuing hydro power projects.

But NGOs like the Save Mon Region Federation (SMRF) are of the opinion that these proposed and upcoming hydro power projects would adversely impact the fragile Eastern Himalayan ecosystem, which is also a seismically vulnerable zone that has experienced several major earthquakes over the past few decades.

On April 7th, in response to a petition filed in 2012 by the SMRF, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) suspended the environment clearance granted by the Indian environment ministry for the $64 billion Nyamjang Chhu hydropower project in Tawang’s Zemingthang area. The NGT asked for new impact assessment studies and public hearings for local people.

The NGT also noted that the project promoted by the steel conglomerate LNJ Bhilwara Group did not consider its impact on the habitat of the endangered black-necked crane, which is endemic to the region. The bird is rated “vulnerable” in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s list of endangered species and is listed in schedule 1 in India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972.

The black-necked crane also has significant cultural value to communities in the region. “We connect it with the sixth Dalai Lama who was from Tawang,” said Lama Lobsang Gyatso, the general secretary of SMRF, speaking to Uneven Earth. “He wrote poems on the bird. Apart from local sentiments, the bird has been labelled endangered by law. The Bombay Natural History Society selected Zemingthang [an area within Tawang] as an important bird area for this reason.”

As a result of its activities, the SMRF became unpopular with the government, which branded it as anti-development, leading to the subsequent arrest of its leader and the police firing.

As a result of its activities, the SMRF became unpopular with the government, which branded it as anti-development, leading to the subsequent arrest of its leader and the police firing. Undaunted, after his release on bail, Gyatso’s SMRF, along with another NGO, 302 Action Committee, submitted a memorandum to the deputy commissioner of Tawang demanding a probe by central bureau of investigation(CBI) New Delhi into the May 2nd killing at Tawang. The state government had constituted a magisterial inquiry and suspended several police officers involved in the incident.

Gyatso and his associates reiterated that if CBI investigation into the incident is not done, they will resort to demonstrations in front of the United Nations office New Delhi, apart from protest rallies in Itanagar and Tawang.

Cultural genocide: Sacred Buddhist River in peril in Sikkim

Protests against hydro power projects across India are not new. In Sikkim, communities have been protesting against the Rathong Chu hydropower projects since the mid-nineties, when the Sikkim Democratic Front Party (SDF) government, under Chief Minister Pawan Chamling, had decided to go ahead with a proposed 30 MW hydropower project on the Rathong Chu river, despite tremendous pressure against it, mainly on religious grounds.

Rathong Chu is considered to be a ‘sacred’ river according to Neysol and Neyig Buddhist texts, the water of which is used even today for an annual Buddhist festival – Bum Chu, at the Tashiding Monastery. This has been an important Buddhist tradition since the time of the erstwhile Chogyals (Kings) of Sikkim from the Namgyal dynasty.

Eventually in 1997, under scathing criticism of infringement on cultural and religious rights of Buddhist minorities, the Chamling government decided to scrap the project. Ironically, the same Chamling-led SDF government allotted another project on the Rathong Chu river, a little further downstream, in the year 2006. In fact, the project capacity now was enhanced from 30 MW to 97 MW! While the earlier project was called the Rathong Chu HEP project, it was now rechristened the Tashiding Hydro Power Project.

“We will not stop until we are able to stop attacks on Buddhist religious sites in the name of development.” -Tseten Tashi Bhutia, of Sikkim Bhutia Lepcha Apex Committee.

But local groups continue to fight against these proposals. “We will not stop until we are able to stop attacks on Buddhist religious sites in the name of development”, said Tseten Tashi Bhutia of Sikkim Bhutia Lepcha Apex Committee (SIBLAC), an NGO fighting against the Tashiding and Panan projects, speaking to Uneven Earth.

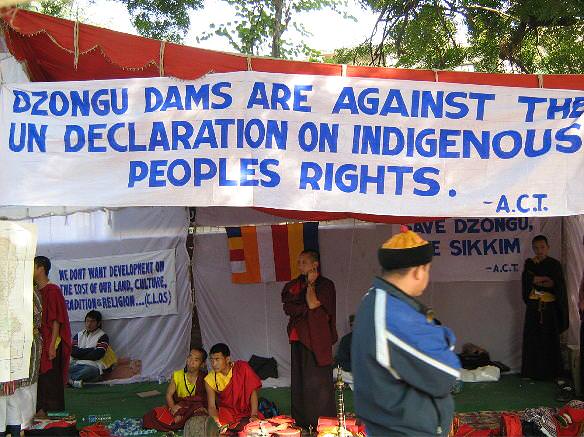

As part of these protests, Sikkim witnessed the longest indefinite hunger strike in the province’s history. The action was called on 20 June 2007 by the Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT), an NGO formed to fight the government’s decision to build seven large-scale hydroelectric projects within the ancestral lands of the indigenous Lepcha community. Although the Lepcha are also found in other parts of India and in Nepal, around 86 percent of their 9000-strong population resides in Dzongu.

The Dzongu area was traditionally known as Myal Lyang in Lepcha language or Beyul Demazong in Bhutia – the latter meaning ‘land of sacred and secret treasures’ and the former meaning, essentially, paradise. It was here that, according to legend, the Lepcha god created the first Lepcha man and woman from the sacred snow of the mighty Khangchendzonga (Kanchenjunga)—the world’s third highest peak, which the Bhutia and Lepcha revere to this day as a protective deity.

In fact, within the core area of the proposed Panan hydroelectric project (300 MW) are a host of sacred sites: the Kagey Lha-Tso Lake, the Drag Shingye caves, and the Jhe-Tsa-Tsu and Kong-Tsa-Tsu hot springs, which are said to be endowed with healing properties. Indeed, the entire northern district of Sikkim has numerous such ‘treasures’, each of which was blessed by Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), the patron saint of Sikkim. Panan is one of the more disputed projects proposed for Dzongu – an area not only sacred but also falling dangerously close to the Khangchendzonga National Park, an area rich in flora and fauna.

The hydro bubble is bursting in India

Hydro-power projects are often proposed as a tool for profit generation, local economic development, and a renewable, sustainable source of energy generation. However, this win-win situation is turning out to be a nightmare of sorts with most of the ‘clean’ energy projects in these states failing to take off after several years of having signed the MoU with state governments. In many cases, the registration process they followed flouted the CDM norms, with project design documents often filled with blatant lies.

This is then coupled with delayed projects accruing huge debt—liability burdens which are being passed on to the respective states. After almost a decade of signing their MoUs, both the companies as well as the respective governments have accrued huge debt burdens due to inordinate delays in implementation with pretext after pretext—making many projects economically unviable due to the present day inflation and market rate of interest.

The returns on investments are bad, production cost high, and sale price of a unit of power low.

In the financial year 2015, India generated 1048.7 Billion Units (BU) of electricity, out of which only 133 BU was from the hydro power projects. Out of the 1048.7 BU electricity produced, 90% is sold through long-term power-purchase agreements, while the rest is traded on the short-term spot market. It is here that corporate power producers will have to make their profits.

But Sikkim, with an annual state budget of $315.86 million, has equity participation worth $230 million. Simply put, it took on huge debt to buy equity and with project delays and abandonment, leading to spiraling burdens that are then being passed on to the people. This has resulted in an absurd situation, where the production cost of one unit of electricity has become more costly than the sale price.

In March 2016, India’s ministry of power intervened to restore three stalled power projects in Sikkim; Panan (300 MW), Teesta VI (500 MW), and Rangit IV (120 MW) with total installed capacity of 920 MW. In a meeting held at New Delhi between the Sikkim government, the private developers of these projects, and the national hydro electric corporation of India (NHPC), Sikkim was asked to either incentivize the independent power producers, or cancel their MoUs after compensating them for investments in the projects.

The independent power producers are not keen on further investments, as breaking even will be impossible in the short term. The returns on investments are bad, production cost high, and sale price of a unit of power low.

The mega hydro power projects that fail

Hydro power projects all over the world are subject to widespread criticism for alleged human rights violations. Apart from the catastrophic environmental and geological disasters they trigger, they also resort to land acquisition—often forced—leading to displacement of people. These mega projects are most often imposed upon people in the garb of development; allowing a nexus of governments in collusion with corporate entities engage in this process of plunder. International funding agencies like the World Bank and private equity investors pump in huge quantities of money. Often, these companies or their front (shell) companies are based in tax haven countries and the money trail is obscure.

These mega projects are most often imposed upon people in the garb of development; allowing a nexus of governments in collusion with corporate entities engage in this process of plunder.

For example, in South America the Yacyretá Dam on the Parana River, which lies on the border between Argentina and Paraguay, generated controversy and criticism during its planning and construction, and is often referred to as a ‘monument to corruption’. While initially the construction costs of the dam were slated at $2.5 billion, eventually they escalated to $15 billion.

Environmental and social impacts run rampant. In China, the Three Gorges Dam project was held responsible by scientists and environmentalists for causing draughts in the upstream of Yangtze River and for increasing the frequency of landslides and earthquakes along areas next to the structure. The project also submerged a number of factories, mines and waste dumps, and a few industrial centres, which are alleged to have polluted the river. Biodiversity experts believe that the Three Gorges Dam has affected hundreds of animal and plant species in the Yangtze River and threatened the fisheries in the East China Sea.

Another glaring example would be in Brazil. Best known to the world for football and samba—and the upcoming Olympics, the country is now in the limelight for anti-dam protests against the Belo Monte Dam project which has been under construction since March 2011. The project, situated on the Xingu River in the state of Pará, faces fierce resistance from the Xingu’s Indigenous peoples and social movements, with support from international agencies.

With an expected 11,233 MW installed capacity, Belo Monte will be the world’s third biggest hydroelectric project when it starts full-fledged operation in 2019. The project was first proposed in 1975 but subsequently abandoned due to stiff opposition from environmental activists and local people. It was redesigned and revived in 2003, and received partial environmental license from the Federal Environmental Agency (IBAMA) in February 2010. The redesigned project, which is being constructed with an estimated investment of $13bn, is now battling at national and international tribunals against charges of displacing thousands of indigenous people and devastating over 1,500km2 of Brazilian rainforest in the Amazon basin.

In Tawang, hydro power projects have also failed to meet development promises by the government. While work on 13 hydro-electing projects in Tawang is currently going on, the government has planned a total of 28 mini- and micro-dams in the district. Even though the power requirement of the district is 6.5MW, if all these mini and micro projects were to produce the electricity as shown on paper, it would be more than 20MW. However, even after many of these projects were completed, they failed to produce adequate electricity, so much so that there are long hours of power cut even in Tawang’s sub-zero temperatures.

Conclusion

Development of every nation comes at a cost. The complex nexus and vested business interest of corporate groups, international funding agencies, private equity investors and powerful politicians have created a systematic plunder of natural resources, be it water or coal. However, development needs to be sustainable and not detrimental to the environment. The May 2nd killing in Tawang is a grim reminder to the policy makers that the development path chosen was fraught, to say the least. Globally, due to inflation, escalation of project costs and low returns on investments, many mega projects have failed to deliver as expectated, some have even failed to take off and too many have led to dissidence, socio-cultural rifts, and environmental disasters.

Soumik Dutta is a Graduate in Economics from Scottish Church College University of Kolkata, and a a freelance investigative journalist covering hydro power projects and protests by affected people, corruption of government and corporations, and environmental violation by infrastructure projects. He has published his stories in the likes of Outlook Magazine, Cobrapost, hundredreporters.org, and thirdpole.net. He loves travelling, music, reading, and good food.

To receive our next article by email, click here.