by Panagiota Kotsila, Salvatore Paolo De Rosa & Ilenia Iengo

The relationship between nature and society is one of co-evolution in which the question of how power is distributed is central. Political Ecology can untangle how the structuring of socio-ecological relations may reproduce injustice or afford openings towards emancipation. Like a toolbox to unpack and understand the complexity of the socio-ecological crises we live in, political ecology is dedicated to a more just and inclusive world.

As a field of inquiry, Political Ecology has many roots and branches united by the common endeavour of observing, analysing, reflecting upon, and communicating how environments are produced by the interaction of social and biophysical processes. Political ecologists document the power struggles that make and remake “the environment”. They provide an understanding of the environment as a dynamic material reality, with exchanges between human and non-human actors, as well as a symbolic arena where different (and often clashing) knowledges, desires and ideologies are cast. Political ecologists claim that the natural and the social spheres are inseparable in practice. Nature and society are constantly co-constituted through processes of co-evolution, and their relationship is fundamentally shaped by power and meaning.

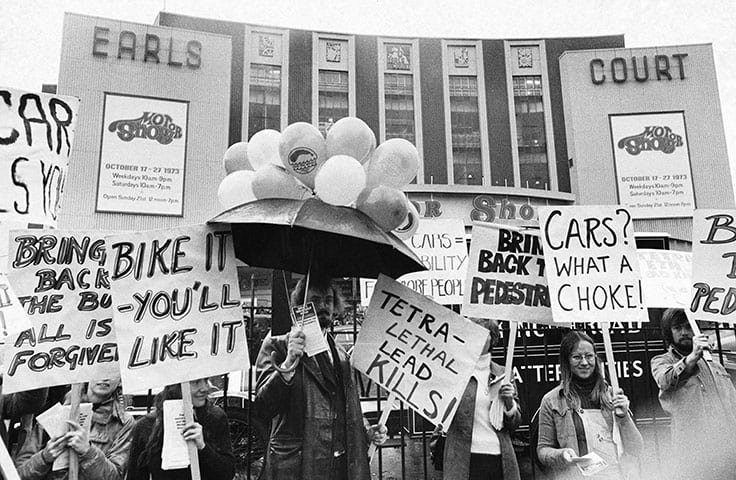

Political ecologists document the power struggles that make and remake “the environment”

Political ecology is the child of human geography, cultural ecology and development studies. In its infancy (1980s-90s), it was concerned mostly about environmental degradation, rural development and the Global South, where it examined the uneven distribution of ecological costs and benefits, and the resulting socio-environmental conflicts and grassroots resistance. Later on, it attracted attention from fields such as anthropology, science and technology studies, feminism and public health. In a nutshell, political ecology developed as an approach that could tackle complex socio-natural phenomena in a novel, encompassing and transversal way.

Many have called it a trans-disciplinary, supra-disciplinary, or even un-disciplined field, due to its incorporation of theories, methodologies and practices from different academic and non-academic arenas. From a rather elusive area of study, political ecology is becoming a strong, ever-evolving and diverse field of its own, of central importance and reference in the contemporary times of climate emergency and socio-environmental injustices, democracy crisis, planetary ecological degradation and widening inequalities.

Political ecology’s main pillars are two (anti-)claims:

1. The anti-Malthusian argument: Resource degradation is not due to general population increase, but to the relentless extraction of resources for the (over-)production and consumption of commodities, which benefits some while threatening the livelihoods and survival of others. Furthermore, in a globalising world, attention needs to be paid to how different scales meet, i.e. to the connections between proximate causes of environmental change and degradation, and the more distant but powerful processes that contribute to such changes. Extreme floods, for example, are not only due to local forest clearing and land use change which might include unauthorized construction, but are also reinforced by increasingly abrupt weather events as part of global climatic change, which in turn is exacerbated by those same land use changes and uncontrolled urbanisation patterns. Political ecologists recognise these connections and underline the powerful interests that motivate and perpetuate such changes. In this vein, the discipline resists declaring this era simply as the “Anthropocene”, which represents the human species acting as one in the process of degrading the planet’s resources and altering its biophysical processes. Instead, it places attention to the political and economic histories and specific actors that produced the current global ecological crisis. This means paying attention to how unevenly distributed the responsibilities and adverse outcomes of such crises are, in turn reflecting power relations in society (hence claims for the Capitalocene, Chthulucene, Anthropo-obscene, Wasteocene or even White (M)Anthropocene).

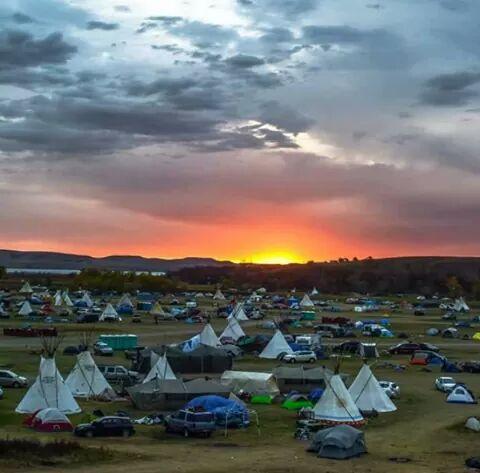

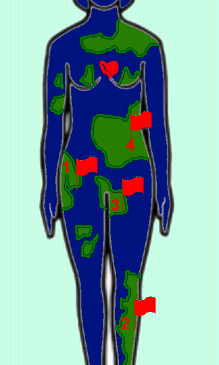

2. The anti-apolitical ecologies: Or, in other words, nothing in “nature” is simply natural. While political ecology relies on strong ecological thinking, it also recognises that what we know of nature, and the imaginaries we hold of it, is a result of historical power/knowledge asymmetries. These include colonial views and conceptualisations of the biophysical environment (e.g. wilderness, pristine forests, etc.), which have come about, survived to this day and become hegemonic through violent practices of injustice and domination over indigenous populations of both humans and non-humans. Urban Political Ecology brings this “nature-cultures” understanding to the urbanization process. In opposition to the interpretation of cities as unnatural spaces, urban political ecology claims otherwise. It focuses on the socio-environmental injustices that come along with processes of altering, (re)producing, negotiating, (re)distributing and (re)imagining socio-ecological configurations in the process of urbanization, urban planning and urban life. This means paying attention to the lived experiences of environmental racism, grassroots claims for the right to live in healthy environments and the growing coalition politics of emancipatory feminist, environmental and decolonial commoning experiences in urban contexts and beyond.

Nothing in “nature” is simply natural

What politics?

For those doing Political Ecology, scientific research is not detached from knowledge/power relations and this recognition has multiple repercussions on how most political ecology is being carried out, or at least, the goals it sets for itself. First, political ecologists believe that considerations of justice, equity and fairness in relation to race, gender, class, ethnicity and other socio-cultural and material inequalities, should be put at the center of research practice and should constitute a shared horizon of values towards collective emancipation. Second, political ecologists often take a position of solidarity with movements that defend humans’ and nature’s rights, and with disenfranchised and often marginalised people that struggle for their voices and claims to be heard. Third, attention is paid to critically reflect on how one’s own position in terms of geography, class, gender, cultural background and interests, influences observations and the whole research practice. Researchers often align and engage with movements but are careful not to romanticize or misrepresent them, as well as not to over-exploit them as informants without giving back.

At the same time, a recent wave of post-/de-colonial thought has increasingly informed political ecology, pushing for the decolonization of political ecology literature, the recognition of non-white and non-western authors, including the doing away with barriers between “researcher” and “research subject”, recognizing various forms of knowledge making, and visibilising the valuable contributions of thinkers outside strict academic silos and outside of academia tout court. Along the same lines, a powerful feminist “turn” in the field is paying attention to intersectionality of power subjection (that includes but is not only about gender or women).

A more serious account of the affective, emotional and embodied experiences of people with/in nature can help to understand socio-environmental conflicts and movements

Feminist Political Ecology accentuates the importance of decolonising what we know of the world, revisiting knowledge gathered and generated by white western men in powerful institutions during and beyond colonisation, and open up to voices, words and meanings offered by subordinated cultures, non-binary subjectivities and minority peoples. Feminist Political Ecology is further advocating for a more serious account of the affective, emotional and embodied experiences of people with/in nature and in projects of ‘being in common’. This will help to understand the nitty-gritty of socio-environmental conflicts and movements, focusing on how different, ever-changing and interdependent the lives of humans and non-humans really are. This is, as Feminist Political Ecology asserts, what can give space for situated knowledges to replace colonial and universalizing accounts of the complex worlds we are part of.

What ecology?

Political ecology, however, is confronted with a number of internal tensions, much of which boils down to the question of what constitutes “ecology” and thus, what ecology do we stand for and imagine for the future? If nature cannot be seen separately from society and power relations, what are the environmental principles and ethics that the field goes by? While much of Political Ecology offers a deep analysis of the why and how in socio-natures and related conflicts, only some goes as far as sketching a more concrete way forward.

Aligned with pertinent debates in Political Ecology, degrowth is a movement of activists and intellectuals which inspires, and is inspired by, grassroots practices reflecting on and experimenting with post-growth ways of individual and collective lives. Degrowth offers alternative visions for socio-ecological relations, which are different to capitalism and real socialism, both of which are based on environmental devastation for the final aim of profit accumulation and competitive power over other states. Degrowth articulates an analytical vocabulary of practice around concepts such as ‘autonomy’, ‘conviviality’, ‘care’ and ‘dépense’. On the opposite side of the spectrum there are the ecomodernist and ecosocialist movements, both considering the public control of the means of production through democratic and horizontal processes of decision making to be the way out of the ecological and social crisis. While according to ecomodernists technological progress will be instrumental in this process, ecosocialists focus on the political and social formations that could bring about such changes.

Degrowth focuses on a radical critique of the growth and productivist imperative demanding a clear, voluntary, democratic and equitable reduction of extraction, processing, transport, consumption and disposal of materials and energy. According to “degrowthers” this is the only way to reduce emissions and abandon environmentally catastrophic processes, while also addressing aspects of inequality and injustice connected to such processes. Ecomodernists and ecosocialists alike, on the other hand, maintain a positivist perspective towards technological innovation and progress, beyond neoliberal propositions of green/blue growth and towards a return to projects that environmentalists had long stood against, such as nuclear power, centralized planning and industrial agriculture. Political ecologists recognise that ideas of nature are social constructions, but they also stand strongly against Western/anthropocentric notions of complete control and domination over “nature”, as this is denying agency both to non-human beings and to non-western understandings of socionatural dependencies and value systems.

Further resources

Peet, R. and Watts, M. (2004) Liberation ecologies: environment, development and social movements. Routledge.

Heynen, N., Kaika, M. and Swyngedouw, E. (eds) (2006) In the Nature of Cities. Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism. Routledge.

Di Chiro, G. 2008. Living Environmentalisms: Coalition Politics, Social Reproduction and Environmental Justice. Environmental Politics. 17(2): 276-298.

Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B. and Wangari, E. (2013) Feminist political ecology: Global issues and local experience. Routledge.

D’alisa, G., Demaria, F. and Kallis, G. (2014) Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era. Routledge.

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Perreault, T., Bridge, G. and McCarthy, J. (eds) (2015) The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology. Routledge.

Svarstad, H., Benjaminsen, T. A. and Overå, R. (2018) ‘Power theories in political ecology’. University of Arizona Libraries.

Álvarez, L., & Coolsaet, B. (2018). Decolonizing Environmental Justice Studies: A Latin American Perspective. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 1-20.

Escobar, A. (2008). Territories of difference: place, movements, life, redes. Duke University Press.

Political Ecology for Civil Society: a “manual” developed by Entitle fellows

Ecologia Politica – Cuadernos de debate internacional

Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., Acosta, A. (2019). Pluriverse a Post-Development Dictionary. Columbia University Press.

Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and The Mastery of Nature. Routledge, New York and London.

Panagiota Kotsila is a post-doctoral researcher at the Barcelona Laboratory for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, ICTA, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Her work looks into political ecologies of health, the politics of urban sustainability and environmental justice from an intersectional and feminist perspective.

Salvatore Paolo De Rosa is a researcher at the Environmental Humanities Lab of KTH (Stockholm). His interests are in political ecology, geography and anthropology while his work focuses on environmental conflicts, socioecological metabolisms and grassroots eco-politics. Currently, he is investigating climate politics in Malmö.

Ilenia Iengo is a scholar activist PhD fellow in Feminist Political Ecology, member of the Marie Sklodowska Curie WEGO ITN at the Barcelona Laboratory for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, ICTA UAB. Her action research is situated in the Southern European city of Naples where she focuses on emancipatory urban politics and imaginaries sprouting at the intersection of transfeminism and environmental justice.