by Lauren Collee

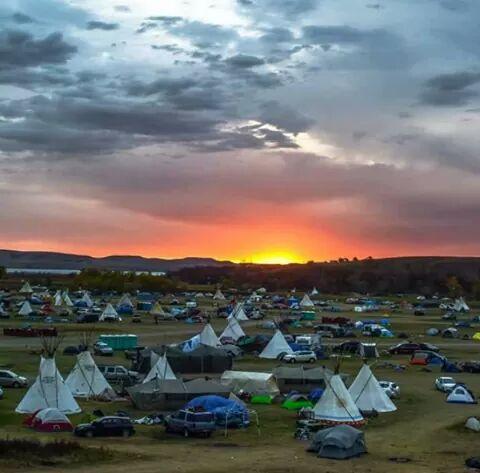

Hirta lies approximately 44 miles from the island of Leverburgh. On the clearest of days, it is visible as a dark smudge on the horizon. If you are a passenger aboard one of the several large cruise ships that stop over each year and deposit up to three hundred bodies on its shores, then you’ll be lucky enough to experience a seamless and convenient visit to one of the most mythologized islands of the Scottish Outer Hebrides.

For everyone else, the journey requires determination—and money. Boats leave from Leverburgh or Skye daily, but book up months in advance, and fifty percent of journeys are cancelled on the day due to unfavourable weather conditions. Overnight visitors must take all their own supplies. There is no shop, no phone reception, no wifi.

The common characteristic of those who end up on Hirta—the largest island in the St. Kilda archipelago, and the only one that permits human visitors—is that they really want to be there. Everyone has their own reasons for visiting: a fascination with remote islands, a desire to witness the one million migratory seabirds that stop by during breeding season, or a drive to master Conachair—the highest peak—and gaze over the precipice of the tallest sea-cliff in Britain. But for most, the allure of St. Kilda lies in that strange thing known as ‘disaster tourism’: the drive to visit sites that still bear the scars of past tragedies, preserved as a testament to their historic importance.

In its simplest form, the story goes like this:

A human population lives for one thousand years, perhaps longer, in complete isolation on a remote island. Their sustenance comes almost entirely from the seabirds, which they catch in great numbers from the cliffs, and store in small stone buildings called cleits.

Then in 1697, an ‘explorer’ called Martin Martin visits, and writes about a forgotten isle that perfectly embodies the Victorian obsession with the Romantic Sublime: the kind of simultaneous awe and fear reserved for thirteen-hundred-foot cliffs, great expanses of water, and mist-filled bowls of land unbroken by even a single tree. Over the course of the following centuries, the Victorians start to come to St. Kilda, in larger and larger numbers.

A priest visits, and preaches the islanders out of their heathen ways. He preaches them out of their windowless stone houses, insulated with lichen and low-lying to escape the worst of the wind, and into new square buildings with real glass. Several winters pass and all the glass is broken. The islanders grow sick. They catch diseases. They are almost entirely wiped out. But they hang on. They keep hanging on for several centuries, until 1930, when the last poverty-stricken survivors are evacuated.

Humans never again return to live permanently on St. Kilda. And so, history stops.

The story is tragic. But the exact nature of the tragedy remains intentionally obscure. Is it the tragedy of globalization? Of tourism? Of the fact that people lived here for so long with so little? The question of whether or not the islanders wanted to evacuate in 1930 is cautiously circumnavigated. The last of the native St. Kildans, Rachel Johnson, passed away last year after having spent most of her life on the mainland. The underlying sentiment in her obituaries is that the secrets of St. Kilda died with her.

The NTS are well aware of the potency of this: a story in which the protagonists are forever lost, set against the backdrop of a desolate landscape peppered with ruined cleits and winged shapes flying in circles against the white sky. The tourist experience is carefully shaped to play off its atmospheric mournfulness. One of the panels in the St. Kilda museum, entitled ‘deserted island’, describes the scene of Village Bay, the small cove where boats pull in and from which the large majority of tourists do not stray:

This row of houses with ruined buildings and storehouses is part of a cultural landscape which evokes the lives of the isolated community that lived here.

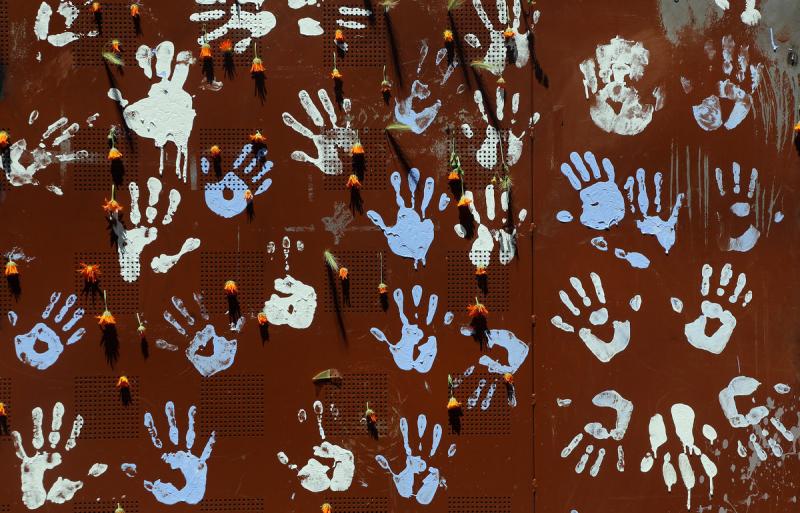

These ‘evoked’ lives can never be anything other than past tense and ghostly. Like the white chalk outline of a body on the pavement, the physical landscape of St. Kilda becomes a space defined by loss. And in the same way that a pedestrian would not simply walk over such a chalk outline, the landscape is governed by rules and boundary-lines. The expected reverence is formalized. Tourists are given a ‘dos and don’ts’ talk by the island warden upon arrival. They are forbidden from walking over the ruins, and if so much as a stone falls out of place, its position must be photographed and logged before the island’s resident archaeologist or NTS volunteer can put it back into its place.

The story that drew me to St. Kilda was not that of the demise of the islanders—at least not entirely. But I was by no means immune to the pull of disaster. It was the final term of my Masters degree in Science and Technology Studies, and I had grown a little restless reading about wilderness from a desk in the British Library. I came across an article on the catastrophic decline of the kittiwakes on St. Kilda, a type of seabird so-named for its characteristic call [kitti-WAKE, kitti-WAKE]. The most recent NTS seabird report reveals that kittiwake productivity has declined by 99.2% since 1994. Last year, a single chick hatched, and subsequently died. The current consensus is that this is due to a combination of overfishing and the global rise of sea-temperatures, which is forcing sandeels—the main food-source of many St. Kilda’s seabird species—to seek cooler waters.

Having no formal scientific training or any experience with quantitative data, I decided that my Masters dissertation would look at perceptions of seabird disappearance. I packed a bag full of ‘survival’ gear (waterproof matches, voice recorder, whisky, chocolate), booked my spot on the boat, sent a few over-enthusiastic emails to NTS staff members, and set off. I received a text from my housemate as I boarded the train to Glasgow: ‘Good luck saving the seabirds. Don’t fall off any cliffs’.

As I dozed my way through the four-legged trip (train, plane, bus, boat) from London to St. Kilda, I tried to convince myself that ‘saving the seabirds’ was at least in part what I was going to do. As a kid I had been adamant that I’d be a ‘nature conservationist’ when I grew up. I don’t think I knew exactly what this meant, and always pronounced it wrong. It was one of those things that I picked up and latched on to because it sounded unquestionably fulfilling.

Disappearance-in-progress isn’t just a matter of erasure and absence. It is bodily. It is complicated. It lacks the soft and elegant tragedy that comes with historical distance. It is messy and off-putting.

But as I grew older, the word became murky and slightly meaningless to me. Interchanged frequently with ‘preservation’, it seemed to suggest that only ‘original’ (pre-industrial) nature was ‘real’ nature. What, then, were the parks and beaches where I spent many happy days during my childhood, those semi-wild places where toilet blocks accumulated new graffiti each year, where shark-nets were put up and taken down, where bushfires burnt through entire stretches of forest that grew back in strange new tufts that looked extra-terrestrial?

The concept of change occupies a strange place in nature conservation discourses. The idea of flux and variation has always been central to ecological sciences, but the need to counteract claims that violent human-induced changes to environments over short periods of time are ‘only natural’ has meant that true ‘wilderness’ has come to be associated with values of stability and a-historicity. As the number of areas that occupy this definition dwindles rapidly, ‘wilderness’ becomes increasingly inaccessible and illusory.

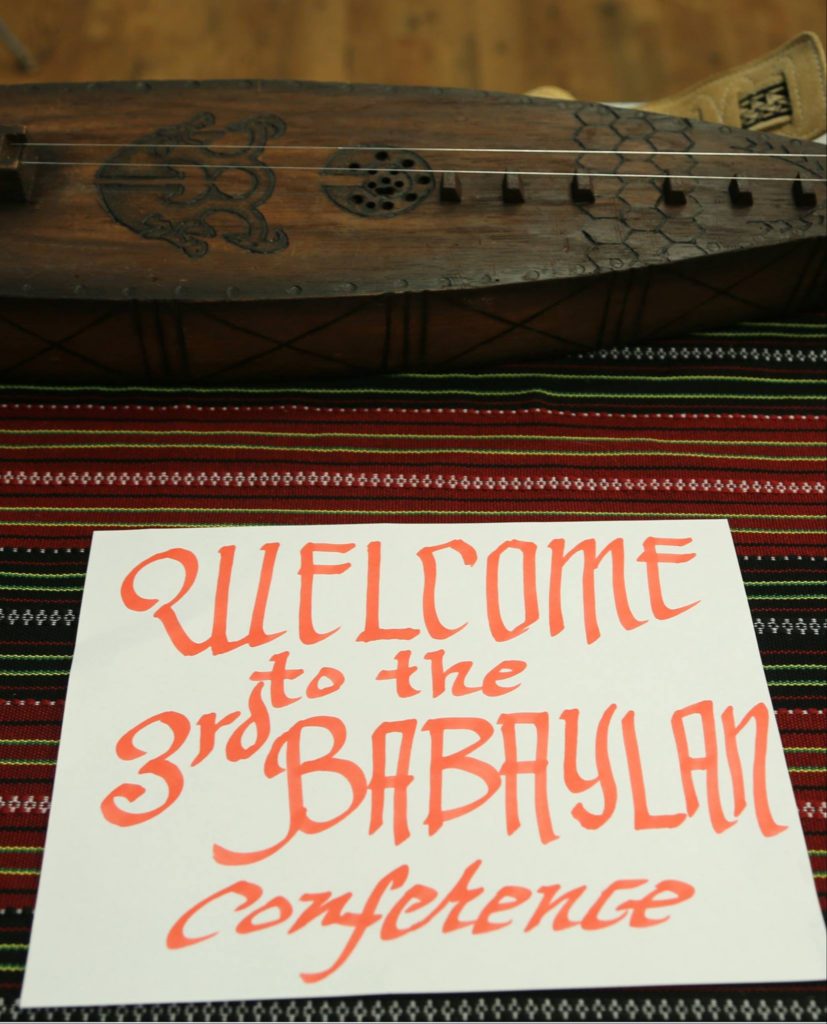

As a Unesco world heritage site with dual (natural and cultural) listing, St. Kilda is a bit of a showroom for definitions of conservation. The division is geographical as well as semantic. Archaeological conservation efforts focus on the ruined village in Village Bay, the sheltered cove where boats pull in. Natural conservation happens ‘out there’, on the rocky outcrops and steep edges of hills that fall upwards in every direction.

Just like the idea of ‘wilderness’ itself, the slow extinction of kittiwakes and other seabirds that come to St. Kilda to breed becomes a ghostly half-reality. But unlike the disappearance-in-history preserved by archaeological remains, disappearance-in-progress isn’t just a matter of erasure and absence. It is bodily. It is complicated. It lacks the soft and elegant tragedy that comes with historical distance. It is messy and off-putting.

The first days I spent walking around Hirta, I saw death everywhere. I found shattered eggshells on rocks. I found the skeleton of a gull picked clean by a larger bird, its wings splayed out on the grass on either side of its exposed breastbone. I walked along the beach and found the deflated body of a seal, and that of a gannet, a splash of white feathers against the rock, intact apart from its missing eye. These dead things did not trouble me. I remembered collecting starfish and seahorses from the beach when I was a child, and leaving them in the sun until all the liquid had dried out of them and they smelled only very faintly. I regarded them with fascination—they were signs of life as much as they were of death.

And then, on the second day into my visit, I hiked up to the top of Conachair and came unexpectedly across a propeller protruding from the hillside, an uncomfortable contortion of scrap metal flecked with an angry rash of rust. I’d heard this story: in 1943, twelve men from New Zealand flew out at night and didn’t expect to find a four-hundred-and-thirty metre mountain in the middle of the Atlantic. The differences between human and animal death and extinction suddenly appeared to me deeply questionable. It seemed strange to me that animal death could be so bodily, so a-temporal and a-historic, and human death so shrouded in the unsayable, the unseeable, so immaterial and yet so steeped in history.

It is easier for humans to understand expanses of time and space when they are packaged up into a story with a beginning, middle, and an end. Museums serve the purpose of drawing up these boundaries, identifying cut-off points and sealing the past in a hermetic bubble that can be carefully curated and preserved. I do not question that this is valuable work, but when a museum is also a living, breathing island, the semantics of ‘preservation’ seem misguided. The conversations around species decline need less emphasis on endings, and more emphasis on the messy present.

On the third day of my stay on St. Kilda, the weather took a turn for the worse and the tourist boats stopped coming. I had presumed that this would be the point at which the real sense of loneliness and melancholy would set in. Now, undisturbed by the bright colours of weatherproof jackets on the hillside, I figured I’d be able to take in the grey-blues and greens of the treeless landscape in all its dreary, ghostly glory.

But the dreariness never came. Life continued. The local boat operators radioed in weather reports, the military helicopter flew in periodically, looking a little like a seabird when its black shape first appeared in the distance, the volunteers carried on documenting misplaced stones, and the wild sheep carried on knocking them off again.

As if time had been turned inside out, my sense of neatly demarcated historical disaster gave way to a kind of joy that was intensely confusing. Walls literally chirped at me as I walked past—I began to see seabirds nesting in the storehouses of their former predators, making their houses in the quarry in the hillside. Slowly, the central absence of the St. Kildans—that chalk line on the pavement—was starting to fade. It became instead a kind of presence, one of the many voices in an impossibly complex orchestra in which things did not displace one another, but instead flowed into the same big mess.

As if performing their unwillingness to conform to human narrative structures (beginnings, middles, endings), the seabirds continued to remind me that an island is never really an island.

One practicality of choosing an island for a museum is that the spatial boundaries seem to reinforce the idea of temporal boundaries. As if performing their unwillingness to conform to human narrative structures (beginnings, middles, endings), the seabirds continued to remind me that an island is never really an island. They did this not only through their vertiginous flight in and out of my field of vision, but also through their response as a population to things that do not—as I was reminded by several staff—fit into the remit of the NTS: climate change, overfishing. One day, two gannets, entangled in a bit of plastic—like a bad omen from a distant land in a fairytale—drifted into the bay and were saved. The outside world seeped into the island-sphere, just as history seeped into the present. The archipelago was doing its best to shake off the impact of the world ‘out there’—the messy present—but of course, no such distinction had really ever existed. The real tragedy of St. Kilda is in its connectedness. But this is also cause for celebration.

St. Kilda is a vitally important asset to the Outer Hebrides, which struggle under the growing trend of depopulation and rely heavily on tourism during the summer months. Tourism to St. Kilda is the NTS’ single biggest source of income. But the old trick of disaster tourism which, in this case, puts the place to death rather than bringing the past to life—does nothing to counteract the story of Hebridean communities collapsing one by one.

The ‘real’ St. Kilda, the one in which tour-operators, military staff, researchers and tourists share space with a whole array of species whose numbers are continuously fluctuating in response to a huge variety of factors, was more interesting to me than the uninhabited island that speaks only of what has been lost. The problem with the word ‘conservation’ is that it implies endings and permanence. This kind of framing is actively misleading in a place where stories of depopulation and species decline are unfolding now, in the unstable present.

But if not ‘conservation’, then what? Perhaps the most useful substitute is simply this: attention. Attention means immersion, responsiveness, sticking with the ebbs and flows. It is what is required of any good reader or listener of stories. It is also what is required of a good tourist.

All photos by Lauren Collee

Lauren Collee is a free-lance writer and researcher based in London. She is interested in social imaginings of the natural world, and ways in which they are shaped by language.