by Gwendolyn Hallsmith

Renewable energy, reparations to the descendants of former slaves and Native Americans, universal basic income, energy efficiency improvements, new transportation systems, job retraining for fossil fuel workers—the list of Green New Deal (GND) aspirations is long and expensive. Senator Bernie Sanders recently released a GND proposal estimated to cost $16 trillion. That’s 16 times the current annual U.S. defense budget, which is about $1 trillion. U.S. GDP was $20 trillion in 2018. How does the U.S. muster federal spending that requires a sum that’s 80 percent of our annual economic output? The Green New Deal requires a LOT of money, amounts that now look politically impossible. Why is money so scarce? Why is there never enough to meet our needs?

Some point to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as a path forward. MMT advocates say we need to stop worrying so much about deficits. The Treasury and the Federal Reserve can issue the money into existence to pay for it all. Inflation won’t be a problem because we can tax the money back out of existence if prices start to rise.

Unfortunately, for the system to work the way MMT imagines it does—that is, for the government to have the ability to simply print money into existence, for free—some critical legal changes are needed: 1) the prohibition Congress passed in 1935 ending the practice of the Treasury borrowing directly from the Fed without issuing bonds needs to be reversed, and 2) the legal requirement for money to be in the government’s account before they spend it needs to be eliminated. Otherwise the U.S. government would be required to borrow the money for the GND from the large, private banks and investors by selling government bonds, as they do now, pay the wealthiest class the added interest, and burden future generations with the astronomical costs of it all.

MMT overlooks the privileged role of the U.S. dollar in the current global economic paradigm. Recent changes in IMF reserve currency rules threaten this privilege, yet we still have monetary power that many nations do not. We could use our waning power in the world to spark a new wave of change in monetary systems and make a Global Green New Deal possible.

What monetary system changes are needed for a Green New Deal?

The monetary system conditions at the root of runaway inequality and environmental destruction are 1) private ownership, 2) debt-based issuance, 3) positive interest, 4) monoculture, and 5) monopoly. All these conditions need to change; the adverse impacts are an emergent property of a complex system, not a simple linear cause and effect relationship between one variable (like positive interest) and one impact (e.g. compulsory growth).

All the government icons and signatures on our dollar notes make us think that the U.S. government issues all the money, but this is not true.

Private Ownership. All the government icons and signatures on our dollar notes make us think that the U.S. government issues all the money, but this is not true. The Federal Reserve System is effectively owned and operated by the large private banks; the dividends they get paid for their capitalized ownership stake are guaranteed at 6% per year, right off the top of the bank’s earnings, tax free. On top of this, since the crash of 2008, the excess reserves the banks hold are also paid interest, decreasing their incentives to move that money into the normal economy with all its risks, shocks, booms, and busts.

We need to make money a public utility, not a private profit center. Strategies include the network of public banks at all levels of government outlined in the GND Congressional resolution introduced this year, and past efforts like the NEED Act and the Chicago Plan. If MMT worked as advertised, it might also be truly public money.

Debt Based Issuance. Between 90-95 percent of the money in circulation in the U.S. is issued by banks when they make loans. That’s right, private banks create money out of thin air as loans and reap the interest as profits. This means that virtually all the money we use is someone else’s debt and comes into existence with the built-in expectation that it will return a profit to its issuer in the form of positive interest. This is one of the reasons there is never enough money for all the things we need, because debt-based money tilts the scales so almost every aspect of human life must produce a return for the lenders, or it doesn’t get issued. If there were money enough to go around, no one would borrow it from the banks—they produce, control, and benefit from money’s artificial scarcity. The scarcity also comes from the fact that when all the money is debt, there is never enough to pay back all the interest.

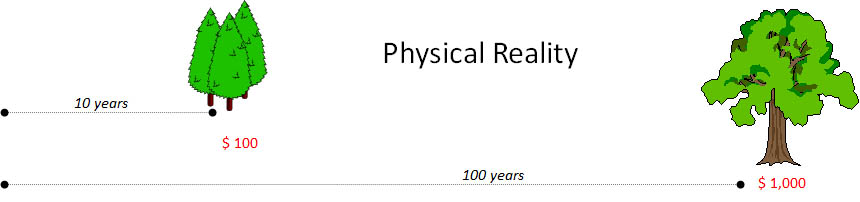

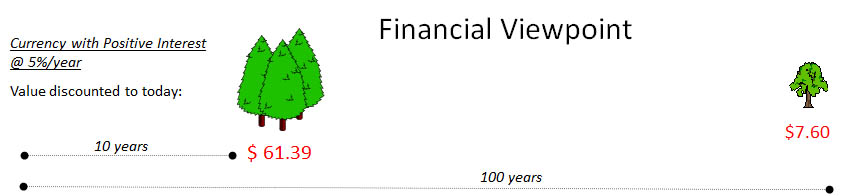

Positive Interest. Positive interest on all the debt-based money drives the discounting/net present value calculation large investors use when they evaluate the long-term value of investments. Discounting systematically devalues the future, which undermines all the efforts we make to leave a better world for our grandchildren. One way to envision the unfortunate effect of discounting is to picture something simple, like a tree, and look at what net present value calculations do to warp the way we value it with money.[1]

Here is the tree’s physical reality. The seedling is planted, and after 10 years, we’ll assume the tree’s value has increased to $100. After 100 years, at this rate of appreciation, the grown tree would be worth $1,000. Both values are in current dollars.

Here is the same tree when viewed through the lens of net present value. The net present value of the tree after 10 years is a lot less (discounting $100 over 10 years), and looking out 100 years, it’s worth almost nothing (discounting $1000 over 100 years).

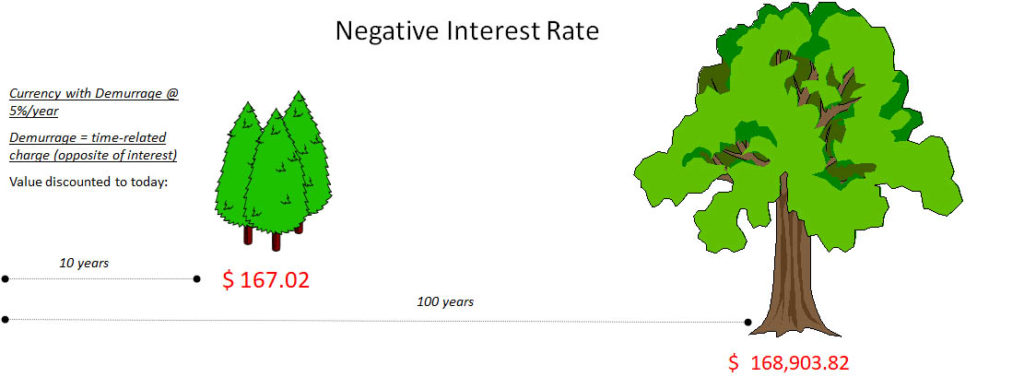

The following illustration shows how the assumed value of the tree would change dramatically if money did not come with inflationary added interest built in but rather had some kind of storage charge, or demurrage, for keeping the money idle (instead of the rewards we give the banks now for excess reserves).[2]

Money issuance needs to be a mix of debt and “grants” (for lack of a better word). Grants would not come with debt’s positive interest and could be used for public and private goods that do not promise a financial return. Education, health care, child and elder care, the arts, and democratic participation are all examples of human activity which cannot and should not be profit centers for either public or private banks.

Monoculture. Even though world currencies come in lots of flavors – Dollars, Euro, Yen, Pesos, Rubles, etc., the majority of them use the same bank debt issuance system. This creates a global monoculture of money in circulation. On a systemic level, this single type of money is as harmful as other monocultures. When the banks fail, the economy fails.

A key consideration for the Green New Deal is that creating different types of currencies could eliminate the artificial scarcity built into the money issued by banks.

Diversifying the types of money in circulation would mean adding public currencies and complementary currencies to the mix. A key consideration for the Green New Deal is that creating different types of currencies could eliminate the artificial scarcity built into the money issued by banks. We can have enough money for everything. We just need different kinds of money. There are already examples of complementary currencies which are used for food, time, care, carbon, data, and small businesses that don’t require bank money to provide a means of exchange to meet these needs. If every currency couldn’t be used to buy everything, this also reduces risks of inflation and accelerating overconsumption.

Monopoly. The laws that require all debts and taxes to be paid in a particular currency (like the Federal Reserve dollars in the U.S.) give the banks a monopoly on money issuance. We need to break the monopoly the private banks have on the money we use and accept public and complementary currencies for debts and taxes. Cryptocurrencies threaten banking monopolies but are still private currencies purchased with bank money. A truly public cryptocurrency accepted for taxes does not yet exist.

The systemic impacts of the current monetary regime have been well-documented in a report to the European Club of Rome by my late colleague, Bernard Lietaer, and others. In brief, these are 1) amplification of the boom and bust cycles, 2) short-term thinking, 3) compulsory growth, 4) concentration of wealth, and 5) devaluation of social capital. All of these exacerbate social and economic inequality, climate change, and other harmful environmental degradation. It is not sufficient to address these problems piecemeal, the solutions we propose must be socially and economically just as well as enabling a safe, healthy, and biodiverse environment. If we change the monetary system, we can transcend the values money has warped which now lead us to human extinction. We can change everything.

Gwendolyn Hallsmith is an author, musician, and activist who lives in an ecovillage she founded in Vermont. She writes and sings about sustainable communities and the new economy.

[1] This is not to say that valuing trees in money is even appropriate. They produce the air we breathe, they protect the water we drink, they offer shade and food and solace. To reduce them and the rest of nature to a dollar value is the main step that leads to economic exploitation, environmental degradation, climate change, and species extinction.

[2] Illustrations courtesy of Bernard Lietaer.