by shrese

Since the 17th of November 2018, a very intriguing movement started in France: The Gilets Jaunes (GJ, or yellow vests, after the high visibility vests that participants have been wearing). Much has already been written about this uprising. I am French, but live abroad, and many friends have asked me for my take on it. This is an expanded version of what I have been sending them.

This is not a “history of the movement”, relating its inception and different stages. That can be found elsewhere (although mostly in French). I just want to list some ideas that I have found interesting along the way. You will probably find that some ideas are in contradiction with others. That’s ok. It’s mostly because I am still unsure what to think of this movement. I have not been part of the movement although I have paid a couple of visits to a small group of GJ on a roundabout in a French village I passed through in late December 2018. This was mainly written mid January 2019.

The demography of the movement and its consequences

I am aware of two studies (one by Centre Emile-Durkheim and the other by Collectif Quantité Critique, also see this interview by sociologist Yann Le Lann) on the GJ movement trying to understand who the GJ are and what they want. One of them has been strongly criticised for its methodology and biases. The other one seems more solid statistically but I haven’t come across reviews of it.

However, both of the studies agree that the main demographic component of the GJ are people constituting the “first layer of included”, that is to say, not the poorest in society, but the layer above: workers and employees. Somewhere between the lower middle class and the working class (classes populaires in French sociological jargon). It is notable that for a large number of people (50% according to one study), this is the first social movement they have participated in.

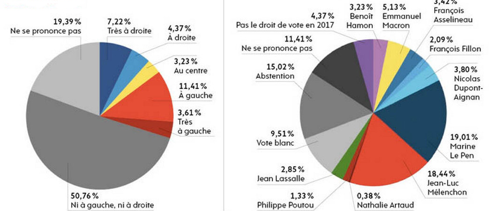

The other main interesting point from these studies is that all political sides are represented in the GJ movement. This seems to be quite a unique feature compared to past movements. The two studies disagree in the numbers, but the most solid one shows (see below): 15% of the participants identify to the Left (shades of red on the left hand side), 11.5% to the Right (blue), 3% in the centre (yellow) and 51% are a-political (neither Left nor Right, dark grey). On the right hand side is shown who the respondents voted for in the first round of the last presidential election. There has been much debate around the influence/role of the far right in the movement. My take on it is that (1) the Far-right (or at least people identifying with the Far-right) has been instrumental in getting the mobilisation off the ground, at least in some regions (2) there are indeed local groups of GJ that are explicitly far right, (3) the National Front (now Rassemblement National) was and still is very strongly supportive of the movement and (4) opinions on migrants usually associated with the far right seem to be widespread in the GJ1. For all these reasons, many who identify as left-wing were quite reluctant to join the GJ on the blockades (at least at the start). I will mention here (as people specifically asked me this question) that there were racialised people on the roundabout I went to visit, as well as in the demo I witnessed in another city. There was also a very interesting call from a decolonial group to join the GJ movement in Paris. So, as far as my experience is concerned, this did not seem to me to be a white-only movement ripe with racism.

What it says about the outdated rhetoric/practices of the Left

I will summarize here (or just plainly translate) one main argument developed in an article especially helpful to decrypt this movement.

The GJ movement, rather than being based on ready-made ideas, or on a shared class consciousness, depends above all on local socialisations, historical or present day, in cafés, associations, sports clubs, housing blocks, the neighbourhood… There are no certainties nor ready-made interpretations of the world, it is constantly on the verge of explosion or dissolution, fluid and adapting, free from the Left’s pathological intellectualism and idealism, and their fantasies of proletariat, historic subject and universal class.

In the same way that the election of Macron was another signal of the crumbling of social-democracy, the GJ movement shows the crumbling of the “communistes, (in)soumis, gauchistes, anarchistes, membres de l’« ultra-gauche » et autres professionnels de la lutte de classes ou porte-paroles radicaux chic” (I wanted to leave the French version here, it reads better. It’s essentially a sarcastic list of the different sections of “the Left”). The tenacity and early victories of the movement reveal the ongoing decomposition of the leftist movements and their obsession and rigidity with their own heritage/practices/language/posture.

Far from being an obstacle, it is precisely the ideological impurity of the mobilisation (which has been decried so much) that has, until now, allowed its extension and rendered obsolete the calls to convergence and unification coming from specialised activists and organisations. To the professionals of the leftist order and of the insurrectionist disorder, the GJ movement simply answers with an invitation to a journey. An invitation to a free participation as whoever one may be, disentangled from the material heaviness and past ideologies of instituted collectives.

On a separate note, it is worth mentioning that this article also suggests a central theme to the movement, mobility. The GJ movement is the first mass politicisation of the ecological question in France. This is why “labor” should not be thought as being at the centre of the situation (as the outdated left keeps on trying to). It reveals the ecological injustices (the rich are way more responsible of the environmental catastrophe than the poor) but mostly, it reveals major differences in relation to mobilité (as in, mobility, circulation, flow or movement, it is a difficult term to translate): “Rather than expressing a social position, it brings up mobility (and its different regimes, constrained or chosen, spread or concentrated) as the principal aim of the mobilisation, and, in blocking it, as the principal instrument of the conflict.”

Gilets Jaunes, a right wing movement?

Drawing on this last point of “ideological impurity”, some interesting arguments coming from the Left have been made in fierce criticism of the movement. I have found these analyses useful, but I am actually not sure I agree with them.

In essence, the idea goes like this:

-

This movement shows a strong rejection of political parties, unions and “the system” in general,

-

In the polls, as well as reclaimed by numerous GL themselves, the category defined as “a-political” (neither Right nor Left) has strongly emerged,

These two characteristics reproduce, or are reminiscent of, the neoliberal project, a project that:

-

Aims at delegitimising (and destroying) the institutions of regulations of the economy, the unions, the social security and the welfare state in general

-

Is hammering in our consciousness that politics is dead, ideologies are useless, there are no limits to anything (“nothing is real!” as the parody of postmodernism goes).

Another way to put it is that the GJ is the mirror response to Macron who, during his election campaign, presented himself as the theoretician of the “en même temps” (“at the same time”), as in: I am on the Left and on the Right at the same time, implying that these are old and useless categories, the “Old World” as he put it.

“When there is no -ism, we adopt colours”: the yellow vests, the red hats (another past struggle in France), the Orange revolutions in Eastern Europe, the red scarves (the recent counter-GJ mobilisation in Paris)… This absence of political tradition could also explain why so much of the imaginary of the French revolution is called upon during the movement: a return to basics (ie, to the official history learnt at school).

A further interpretation is to find similarities between the GJ and what is now deemed as “populist” (commentators tend to put all sorts in this populist bag: “illiberal” democracies, Brexit, Trump, Orbán, Putin, Mélenchon, Podemos etc.). The similarity lies here in this shared narrative of the “good” people set against the corrupt elite/cast, the rejection of the “system”. What some see as problematic is that, here, the “people” is seen as some sort of a homogeneous group, and the main confrontation in society is between the people and this “elite”. The other lines of potential conflict (class, sex, race…) are not considered, hidden or consciously put to the side.

This is more or less what I was told on the roundabout: “We do not talk about the sensitive stuff”. In contradiction to that, I did witness discussions on “hot topics” (sexism for example) in that same group, and even though there were some quite contradictory points of views expressed, there was an amount of care, ability to listen, non-judgement and non-resentment that exceeded a lot of the activism-related spaces I have been into. The people I talked to said that they wanted to avoid arguing because they want to be as open as possible, and they do not want to be divided. As if the fact of being together on the roundabout meant much more than the political identity of the group and/or its demands.

These three aspects (the vision of the people as a homogeneous group where the only line of contradiction is with the “elite”, the self-identification as “a-political”, and the rejection of ideologies) is also problematic for another researcher, Samuel Hayat. For him, it is an imaginary where politics is replaced by a series of policies, the neoliberal dream. Both the GJ and neoliberalism are telling us that we should rid ourselves of ideologies, and that politics should be seen as a list of problems to solve, separated questions to answer, boxes to tick. Another problematic aspect of this is the denial of the positive role of conflicts and contradictions within a movement and for “democracy”. However, Hayat is on the whole very supportive of the movement and hopes it will find a way to use its internal contradictions to build power.

Some on the Left push this interpretation to the extreme, for example the Collectif Athéné Nyctalope. They see the GJ movement as essentially reactionary. They interpret the original impetus of the movement, and most of its demands (including the now most visible one: the inscription of a kind of Citizens’ referendum in the French constitution), as owing to the Far-right. Because portions of the Left are supporting/taking part in the movement, this would be tantamount to making alliances with the Far right and fascists, basically using the principle that “the end justifies the means”. As a support to this view, this collective draws extensive comparisons between the GJ movement and the M5S in Italy.

In this vein, the following point is also interesting. To increase one’s available income, there are two main options: increase your pay, or decrease your tax. The GJ have mostly focused on decreasing taxes, which could be argued is a typical right-wing demand, facilitating the kind of disturbing alliances seen on the ground (with shop owners, heads of small companies, local right-wing politicians, far-right…).

Its tactics, practices and “victories”

The blockades

As far as I know, these were used on the roads/highways, at tolls and, most famously, at roundabouts (which are very numerous in France). This tactic of blocking the fluxes (transport of goods, people, money, information…) was particularly pushed by the Invisible Committee (see The coming insurrection and the Chapter “Power is Logistic. Block Everything!” in To our friends), and it is now particularly interesting to see it taken up so “naturally”. So you could say: “the Invisible Committee was right!” or “the GJ are highly politically conscious of the situation and know what to do to influence it”.

Decentralisation

This has been the practice as much during the big national days of action in Paris (every Saturday since the start of the movement), as well as at the national scale. In Paris, as far as I could gather, there was no real central banner, no head of the demo, no core group, no stewards (this has actually changed recently, with main banners and some sort of stewarding in places, but the last Saturday in Paris still saw five independent demos). The level of militancy reached very high levels, including in previously untouched areas of Paris (even in the protests of 1968, the rich quarters of Paris stayed intact). But Paris has not been the centre of the movement by any stretch. All regions, cities and towns of France had their group of GJ, strongly anchored in their territory. It has so far been impossible to establish some kind of physical, organisational or even symbolic centre to this movement.

Refusal of representation

A reflection of this decentralisation is the knee-jerk reaction of hatred by the GJ for any attempts at representation (no legitimate representatives, no official spokespersons etc.). Despite many efforts, self-proclaimed leaders have so far been quickly de-legitimised and even threatened, unions and political parties very much pushed to the side. Some interesting calls for coordination (as in, not convergence nor unity nor centralisation) were proposed, but I don’t know how much they were followed and how big the risk of institutionalisation/recuperation would be if they were2.

Victories

Because of all this, the media don’t doesn’t know how to report on all this. Most of the GJ are not the usual suspects of social movements/unrests (lefty activists, students, trade unions, the youth of the banlieues etc.), so journalists are lost and cannot use their usual clichés. They don’t know what to say, nor how to understand it. The movement is really popular and enjoy large support (even after the very riotous Saturdays) so it’s difficult for them to completely bash it. As there is no central organisation or official spokespersons, the media need to go to random people to know what’s happening. So you end up hearing voices, accents, seeing bodies that you never find in the media. This is the case in terms of class, but also of gender. Indeed, official representatives of social movements tend to be mostly men, therefore women are more visible now than in previous movements. The previously cited studies show that there are as many women as men involved in this movement, there has even been a Women’s GJ demo on Sunday 7th January.

I have never seen a government showing so much fear. They talked about insurrection, an unprecedented crisis, a toppling of the republic, about risks of death during demos, they warned and even threatened people not to go to the national days of action in Paris. Of course, the rhetoric of fear could also just be an act, but it’s the first time I have witnessed this. The repression is extremely violent, fierce (many documented severe injuries due to shots of rubber bullets to the face, for example) and orwellian (thousands of pre-emptive arrests on charges such as “gathering with the intent of committing violence”), this could also be a sign of fear. The government also seems totally lost with the decentralised aspect of the movement: They tried to get delegates to come and negotiate with them. So some self-proclaimed people went, but were immediately repudiated online by other GJ. However, interesting to note, when these self-proclaimed spokespersons had their meetings with ministers and others, they filmed and livestreamed it, which was a first.

To stay on the subject of the repression, there is something with the GJ movement and its relation to the police that seems quite interesting to me. As already mentioned, the movement shows a wide diversity of political opinions, including far-right people. Therefore, a lot of people on the blockades do not necessarily share this natural hatred of the police, they may see them as their “comrades”, talk to them, feel connected to them (although I’m not sure how widespread this still is after the violent police repression). On top of that, as the GJ can hardly be perceived as the usual suspects of social movements, it must be confusing for some police to bash at people they would never expect to face (including other fascists). Is it possible that at some point some police will refuse to keep on gassing and beating them up?3 It is also interesting to hear police unions saying that they are at breaking point, exhausted etc. (they even threatened to start their own movement in December and got immediate pay rises).

Conclusions

To conclude, it could be argued that the GJ have a very acute strategic sense of the political situation. A first sign of this are the actual victories/retreats from Macron that the movement achieved. These are more impressive than most of the concessions secured by the social movements I can think of in the last three decades (even though, given what is at stake, they are of course pretty insignificant).

This is without mentioning the other kind of victories: the level of militancy and confrontational practices, the obvious fear instilled in the government and the state (hard to measure how much businesses and neoliberal proponents were scared), the social question put at the forefront of the ecological question (i.e., the ecological transition has to include the social question, not just increase tax on fuel that will mostly impact on the poorest without any systemic change), the significant and meaningful human relations (and “political consciousness” for lack of a better word) created during the movement.

Let’s focus a bit more on this latter point. This was very much confirmed by my visit to the roundabout. Not only were the local groups of GJ based on already existing relations (neighbourhood, village, social or sport clubs, families…), but what seemed to be essential to the people there was to finally get to talk to new people around them, break the isolation, discover each other: “I don’t know them but we talk to each other”. Anything that helps us filling the emotional desert we find ourselves in everyday… even better when it’s in confrontation with a system, or rather, a mode of life. One GJ said on a TV debate: “Mais tout est scandaleux ! – But everything is outrageous!” when asked what kind of reform the government should make to appease the movement. I loved this. It’s about everything, the way we live, the way we relate to others and the world around us… (I realise that I am here suggesting what could be “the” central question of the GJ movement, but actually I’m struggling to find the usefulness of debating this central question. Everything has already been said and proposed anyway: mobility, recognition of work, arrogance of the elite, feeling of not being listened to and humiliated, living in regions abandoned by the state, contraction of wages and “spending power”, populist/far right agenda…).

Following from this, a useful text argues that, because the spirit of a movement sits more in its tactics/practices than in its demands/ideas, the GJ movement has brought to the forefront the political potency of the localité (locality in English, the text also uses the term commune). As already mentioned, the localité is where the movement started, but the movement also “made it the central point of emancipatory politics again”. It is the “potential nucleus of a coming political subjectification, antagonist to the present and future spheres of representation”.

Shrese is from France, has lived abroad the last decade and is sometimes involved in the housing movement, amongst other things. He likes the Invisible Committee a lot and tries really hard to not treat their books as the bible.

1. This is based on a general impression and on one of the questions asked in the study of the Collectif Quantité Critique: 48% of respondents think that, when it comes to employment, priority should be given to a French person over a legal migrant. So all in all, my point (4) may not be so strong.

2. As an update, as of the 29th January 2019, it seems that this initiative was a success, at least in terms of number of collective present (75), but from the sound of it, the discussions sounded complicated.

3. There has already been signs of solidarity to the GJ by the police. Eric Hazan says that the successful uprisings are the ones where, at one point, some police/army forces have flipped in favour of the movement.