by Andrew Ahern

It is fair to say that most environmental books and political attention are centered on the climate crisis. And for good reason: for the vast majority of the world, a planet burning past 1.5℃ is existential. But for every article or text written about simply reducing CO2, audiences and the public are left thinking that if we just switch from fossil fuels to renewable energy it is enough to avert catastrophe. As the authors Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettesse of the new book Half-Earth Socialism argue, we have much more work to do than simply reducing carbon pollution.

Instead, the authors claim we need a holistic ecological program that puts the economy back into balance with the living world by respecting limits, nonhuman nature, and thinking at a planetary scale. Half-Earth Socialism seeks to do just that through a political program consisting of a variety of policies in the realm of worldwide conservation, vegan diets, and sufficient provisioning to the world’s population.

Where the book thrives in its utopian imagination, its originality in synthesizing disparate thinkers and traditions, and its criticisms of “prometheanism”, it also lacks a strong analysis of democracy, a more thorough argument against some its targets, and at times, can be found to concede to anticipated criticism regarding its more provocative ideas, especially as it concerns veganism.

An original synthesis

As a general summary of the book, the authors begin by describing a dystopian scenario where a solar radiation management (SMR) scheme fails, leading to species loss, acid rain, and reversing the environmental wins from the previous century. Following the introduction, the authors critique the promethean worldview that seeks to dominate nature, essentially making the nonhuman world a machine of inputs and outputs.

The authors then draw from biologist E.O. Wilson’s idea of conserving half the earth for wildlife and nonhuman nature as a counter to this promethean program. This means protecting large areas of the earth for wildlife to thrive, where Wilson identified thirty biomes across the globe that could largely contribute to this conservation effort. To achieve this rewilding, the authors suggest universal veganism is required due to the vast amount of land animal agriculture uses.

Unlike Wilson, who the authors describe as center-left, Half-Earth Socialism compliments worldwide conservation with socialist central planning. Here they engage with the work of theorists like Otto Neurath and the Soviet mathematician Leonid Kantorovich to explain how utopian socialist planning would work in a Half-Earth economy. The author’s vision for central planning is inspired by the socialist and designer William Morris who was interested in how socialism could offer fulfilling work by integrating labor with arts, nature, and leisure. They end the book describing a future of organic veggie farms, communal living, and life under a centrally planned economy. Half-Earth Socialism’s originality in synthesizing such disparate thinkers is laudable in and of itself.

The author’s vision for central planning is inspired by the socialist and designer William Morris who was interested in how socialism could offer fulfilling work by integrating labor with arts, nature, and leisure

Dominating the non-human

There are many things worth praising in the book. First, their critique of prometheans and ecomoderns who seek to subdue and dominate the natural world is arguably their strongest chapter. In “Binding Prometheus”, the authors take issue with this bipartisan worldview of convserative billionaires, centrist political parties, and sects of Marxism. Vettese and Pendergrass largely blame Hegel’s concept of “humanizing nature” for this ideology. Showing how Hegel’s concept was influenced by Christian theology, the authors describe this “humanizing” as “the process by which humanity overcomes its alienation from nature by instilling the latter with human consciousness through the process of labor.”

In other words, our relationship with nature is only good for what humans can put it to use for: nature becomes nothing more than an instrument, ignoring all the ways not putting nature “to use” is vital for our own species survival. Since the nonhuman world must be instilled with human consciousness (rather than species having their own), this is used as a justification to plunder and even exterminate the nonhuman world.

In this way, the authors tell us, the neoliberals and many Marxists aren’t so different in their attitude towards nonhuman nature. Each agrees nature is to be controlled, dominated, and capitalized: one just believes markets are the best mechanism, the other believes it is nation states. Both free marketers and state socialists fail to account for the agency of nonhuman nature, and they lack critical reflection on the ways this worldview has culminated in our present environmental crises and ultimately promote a secularized religiosity that believes humanity can take a god’s eye-view of nature. “Marxism”, the authors write, “cannot simply be greened by reading Capital with viridian-tinted glasses.” If religion is the opiate of the masses, as Marx said, then prometheanism is the opiate of Marxists.

“Marxism”, the authors write, “cannot simply be greened by reading Capital with viridian-tinted glasses.” If religion is the opiate of the masses, as Marx said, then prometheanism is the opiate of Marxists

Utopianism is good, actually

Another strong point of the text is its unabashed embrace of utopian socialism. Utopian socialism — used as a pejorative by Marxists (who are themselves called utopians by anyone not on the radical left) — has been defined as an early form of socialist thought that seeks to build socialism in the name of it being more desirable than capitalism, rather than as an inevitability, as Marx predicted.

Utopian socialists typically start from a place of what they would like the world to be and experiment in bringing about this better, more ideal society. It is no coincidence then that the authors end their book with a utopian future set in Massachusetts, itself a place of previous utopian socialist experiments.

The authors argue at length about utopian socialism being more than just idealistic dreamers wishing on a star for a better society. Instead, they advocate for a “scientific utopianism” as “blueprints for the future” that they believe can remedy many problems for both environmentalists and economic planners. For environmentalists, the utopian tradition allows the movement to project forward what kind of world we want to build in the ashes of capitalist ruins with a critically anticapitalist edge. Here, the authors tell us, is where we need to contemplate our blueprints for the future that help inspire and mobilize people.

For planners, and the socialist tradition more generally, the authors point out that centrally planned economies like the Soviet Union suffered from an immense lack of imagination and participation outside of the party line, resulting in the lifeless and bureaucratic state that it ultimately became. Utopian socialism in this way allows us to imagine and fight for a world not yet built with the flexibility and experimentation the utopian socialist tradition advocated for.

Given utopian socialism has been condemned by most Marxists, Vettesse and Pendergrass’ attempt to revive a tradition during troubling times is certainly welcomed. Marxism might have many answers, but the socialist tradition has too many layers to simply be narrowed to just what Marx, Engels, and their followers said over a hundred years ago. As a final note, the utopian socialist tradition, like many anarchists and libertarian socialists, has long championed an ecological sensibility and often much more than most Marxists. We can and should explore other options and schools of thought in times of ecological collapse.

A blueprint for utopia

Finally, the author’s exploration of socialist central planning history is fascinating, as well. Here, their planning philosophy is largely influenced by Soviet mathematician Leonid Kantorovich and linear programming (which itself was developed by the utopian theorist Charles Fourier). As the authors explain, the social engineers of “Gosplant” — a play on words the authors develop based off of the original Soviet state planning commission “Gosplan” — would receive information about the local conditions of the social and natural world in order to devise models about what kind of future could be planned. These planners might ask themselves what societal outcomes could be maximized while limiting ecological damage, such as the amount of land that can be used while delivering the necessary energy requirements for individuals and industry. This chapter is the author’s technical “blueprint” for utopia.

To complement what can often be abstract and technical planning language, the authors help manifest what planning in practice is like through their own computer game. And beyond its originality, it is also fun! Half.earth helps the reader experience — from the position of the planner’s seat — what kind of impact certain policies, technologies, and forms of organization have on the climate, biodiversity, and social prosperity. It serves as an especially nice complement to the third chapter in order to help readers better understand programming, planning, and decision making.

Central planning or participatory planning?

Half-Earth Socialism makes many good arguments and interventions to expand the horizons of ecosocialism. With that said, it also suffers, at different points, from a lack of follow-through on some of their more ambitious plans. While the authors repeatedly emphasize the importance of democratic values, they fail to explore, on both a practical and conceptual level, what democracy would be in a centrally planned economy. Because the authors rely so heavily on Soviet thinkers, this oversight is hardly acceptable. Soviet society suffered from an extensive amount of technocracy, bureaucracy, and ultimately, autocracy due to a lack of democratic decision making. It would be wise of Vettese and Pendergrass to look at other utopian thinkers and their emphasis, not on central planning, but participatory planning. One of those utopians is Murray Bookchin.

Bookchin might be the thinker most responsible for making utopia an endearing term during the late 20th century and into today. But Bookchin’s utopian social ecology was predicated on a system of deep and direct democracy. Bookchin looked at Ancient Greece, despite its commitment to patriarchy and slavery, as an example of what democratic structures looked like. The ekklesia, or citizen assembly, was a major institution within Greek society where everyday men would directly contribute and decide the direction of the polis. Greek culture was also imbued with a democratic ethos in the sense that there were dedicated gathering places — the agora — for instilling democratic values in Athenian citizens.

Likewise, a contemporary example of this form of direct democracy comes in the New England Town Meeting. The Town Meeting is still practiced by a number of New England municipalities where at least once a year, town members come to debate and vote on things such as changes to the town charter, the municipal budget, and are able to offer up policies and proposals to be taken up by the town.

Such examples provide a counterweight to the lack of democracy prevalent in centrally planned economies. Contemporary citizens’ assemblies and participatory budgeting are other examples of direct and deep democratic systems being flirted with today and all over the world. Despite Marxists and democratic socialists saying they are committed to democracy, often their horizons end at representative government and unions. Here Bookchin’s distinction between administration—the technical and coordinating work planners would do, and policy-making, where people make decisions through democratic structures like popular assemblies or councils for the planners to enact—is helpful. With this in mind, it can feel like Vettese and Pendergrass view planning as an end in and of itself, rather than a deliberative outcome of democratic politics. Like too many Marxists, their political imaginations are stifled by ruminations about a benevolent Soviet State commanding and controlling from on high.

It can feel like Vettese and Pendergrass view planning as an end in and of itself, rather than a deliberative outcome of democratic politics

The issues with universal veganism

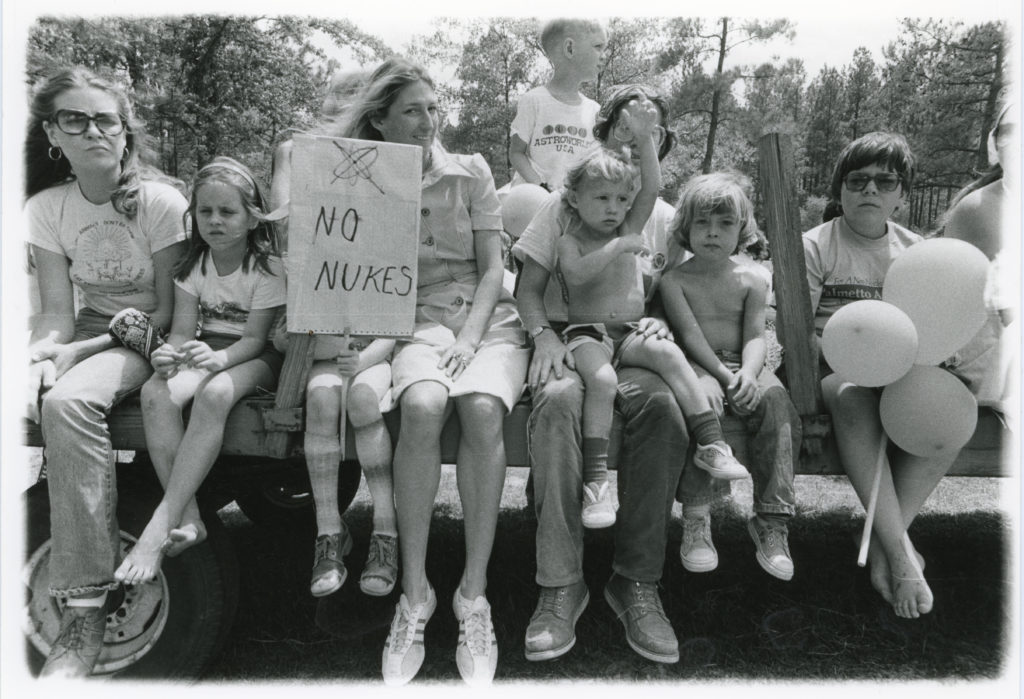

Readers might be turned off by some of the more upending policies Pendergrass and Vettesse propose like universal veganism. One of the book’s strongest arguments for veganism is the large-scale “humanization” of animals for food. The authors point out that, in the context of the 300,000 years humans have existed, zoonoses have only emerged within the last 10,000 years or so — the time period in which humans domesticated animals. With the Covid-19 pandemic originating in a meat market and, by at least one study’s account, at least 60% of infectious and 75% of “emerging” diseases originating from animals, there is more and more evidence pointing out that the “humanization of nature” is actually quite deadly.

While it’s increasingly clear that meat-heavy diets are not only morally problematic but also irrational, the prospects for universal veganism are slim, even in a world with improved plant-based “meats.” This presents a real political problem the authors don’t really address. Yes, we need to reduce meat consumption, but in order to build a coalition powerful enough to reduce current consumption rates, many will be turned off if the “planners’” demands are universal veganism. I respect and appreciate the principles of vegans, but this must be balanced with a proper political analysis that examines a more astute point regarding the unsustainability of Western diets: industrial farming and capitalism.

In this vein, the authors confusingly propose universal veganism but ask animal rights activists to temper their criticisms of Indigenous hunting practices, given that many Indigenous tribes have more sustainable and reciprocal relationships with the animals they eat. This seems to be a concession that there are at least some forms of sustainable animal consumption and that, on both a practical and political level, Indigenous people are vital to preserving the nonhuman world. Furthermore, Indigenous people are often viewed as relevant to protecting nature rather than as direct political participants in how decisions are made about nature—further relegating them to the colonial divide that subjects them to an “outside nature.” While the authors acknowledge that Indigenous people have a deeper relationship with the nonhuman world than western conservationists, a program in the name of “Half-Earth Socialism” is still in reference to one of the West’s most famous conservationists who has influenced the United Nations and other international conservation programs (like the 30×30 program), often at the expense of Indigenous perspectives, sovereignty, and stewardship.

With the lack of attention on democracy in the book and emphasis on top-down central planning, it is more than reasonable to expect already vulnerable Indigenous people to be victims of such a Half-Earth plan. Just because your Half-Earth is socialist, does not necessarily make it equitable, just, anti-racist or democratic given, by the authors’ own admissions, many centrally planned socialist societies were deeply undemocratic. It would be wise of the authors to tackle both the Indigenous and democracy problem together. The authors are correct that we need to vastly expand conservation efforts. It might just not be in the name of “Half Earth” or Western conceptions of centrally planned socialist economies.

With the lack of attention on democracy in the book and emphasis on top-down central planning, it is more than reasonable to expect already vulnerable Indigenous people to be victims of such a Half-Earth plan

Complicating nuclear

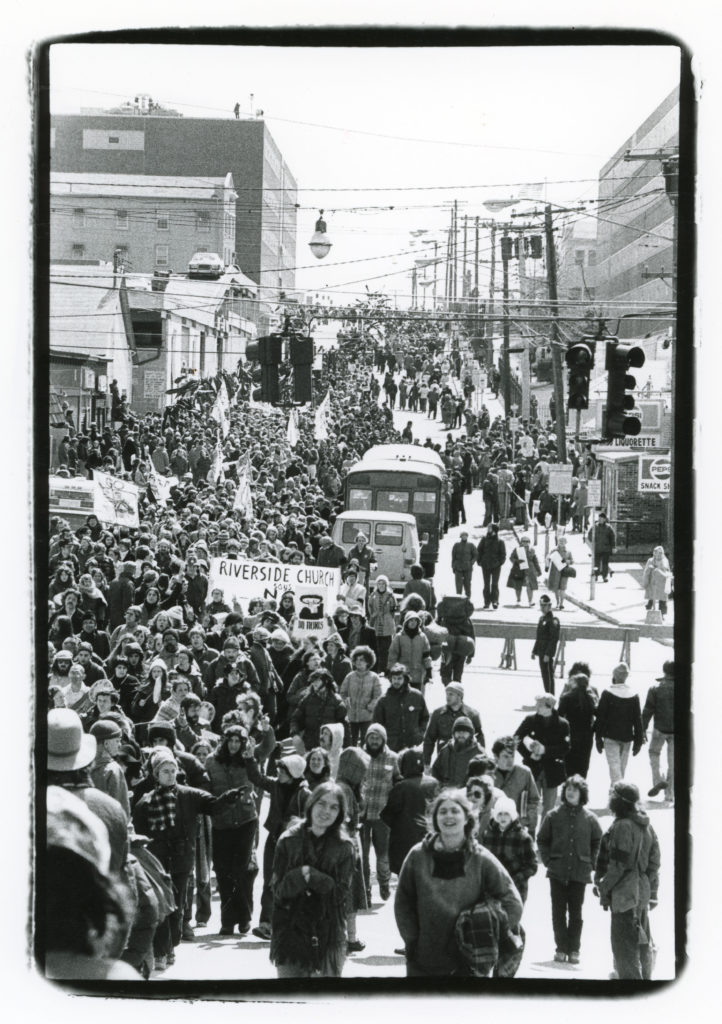

Another issue is the author’s swift explanation for why nuclear energy does not belong within the environmental movement. While I share the author’s criticisms of nuclear energy being an unstable technology given an increasingly unstable climate, the author’s argument hinges on the practicality of not isolating environmentalists who previously formed the anti-nuclear movement. Here, they reveal themselves to be political strategists while the rest of the book is provocative and visionary.

With that said, I do not think ecologists should spend time or resources trying to shut down currently operating nuclear plants. For anyone familiar with the energy debate, you quickly learn how much nuclear advocates suffer from a sort of dogmatism and zealotry when it comes to nuclear power — believing it can power the majority of the world’s electricity needs despite few studies or institutions saying so. This archetype has been referred to as “Nuke-bros” due to their arrogance and chauvinism, oftening exhibiting authoritarian character traits as well (which shouldn’t be a surprise, as nuclear energy requires an authoritarian military). Nevertheless, decarbonization will largely fall on the shoulders of renewable energy, with or without an anti-nuclear movement, in my opinion. But because they move so quickly through their critiques of nuclear power, this, among other points (like the land sparing of nuclear power), is hardly addressed in any detail.

Following the example in arguably their strongest chapter, prometheanism should be critiqued and destroyed from leftist thought all together. And with that philosophy in retreat, we might expect a retreat of nuclear energy, geoengineering, and the senseless killing of animals as well.

Conclusion

Half-Earth Socialism sees the ecological landscape and makes its own unique intervention. Their critique and commitment to a Half-Earth economy is admirable and provocative, even if at times unclear and lacking details on how to form the political coalition powerful enough to bring about their vision.

Unlike many on the Left, Pendergrass and Vettese do not suffer from either carbon or Marxist-tunnel vision, offering their own synthesis and analysis of ideas and thinkers across ecological and leftist thought. Half-Earth Socialism is thinking at a planetary scale. Now we need to think about bringing these ideas to everyday people. To borrow and reword a phrase from the French students of the 1960’s: “Do the impossible! Plan utopia!”

Andrew Ahern is an ecological activist and freelance writer based in Massachusetts. You can follow him on Twitter @PoliticOfNature. Full disclosure: Andrew is a member of Boston DSA alongside author Drew Pendergrass.