by Veronica Gomes and Kimberley Thomas

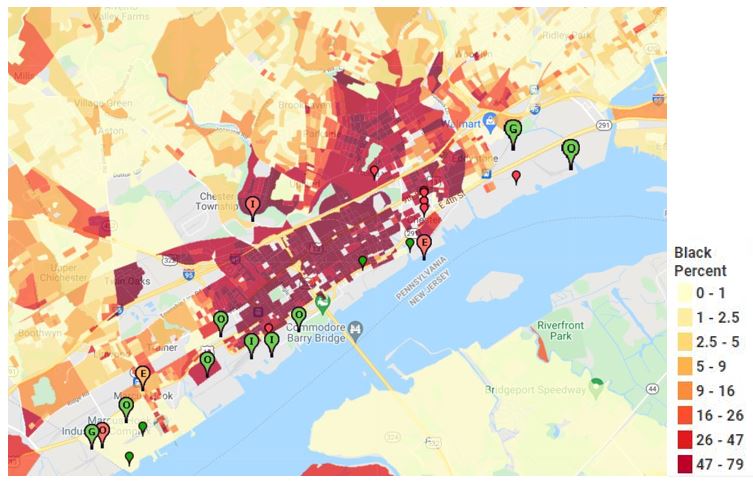

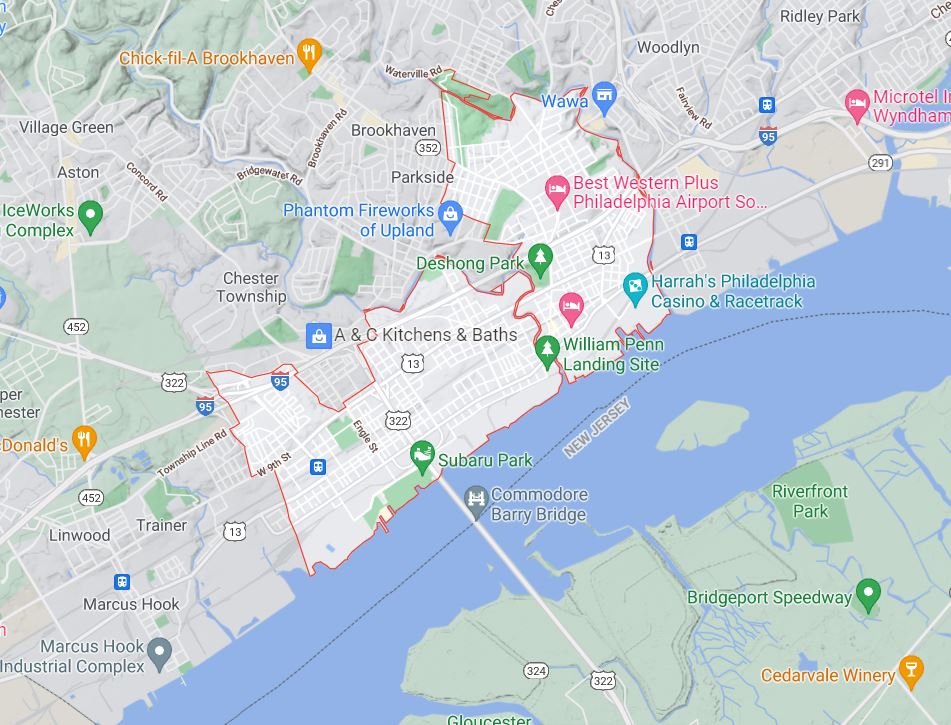

Waste trucks rumbling through the residential neighborhood have become a commonplace scene in Chester City, Pennsylvania. These trucks make their way to the Covanta incinerator carrying tons of garbage from Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and places as far as 115 miles away, like New York. It is the nation’s largest trash incinerator, has very few pollution controls, and has become infamous for burning an astonishing 3,510 tons of trash a day. Trucks disrupting the otherwise peaceful neighborhood have become an extension of the myriad ways in which Chester has been reduced to a burning furnace. The city’s 4.8 square miles are overburdened with trash incinerators, a medical trash burner, a sewage sludge incinerator, paper mills, and a multitude of chemical plants (Map 1). This hub of toxic facilities has disproportionately subjected the predominantly minority population, 70 percent of which is African American, to the perils of environmental pollution. Such environmental harm has been an unwelcome addition to the social ills and disinvestment that Chester residents continue to struggle with in their daily lives. The close proximity between the toxic facilities and neighborhoods with a high density of African Americans is unambiguous (Map1). Meanwhile, such facilities are notably absent from the areas that flank the core African American neighborhoods to the east and west.

Media coverage of the Chester case has uncovered the detrimental health consequences associated with residents’ prolonged exposure to pollution. While the sources of air pollution are varied and difficult to isolate, their attendant health problems have been very certain. Cases of asthma, lung cancer, stroke, and heart disease are rampant and exist alongside lead poisoning from deteriorated housing and air pollution. The pollution has reached the extent that even the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is aware that the facilities violate national air quality standards. While current news articles uncover ‘pollution’, ‘harmful air’, and ‘dirty air’ as the major concerns of Chester, most of the systemic racism ingrained in the continued pattern of toxic facility siting largely goes missing. Only by placing Chester in a historical context does the environmental racism of the toxic dump come into view.

Nations’ worst case of environmental racism

So, when did environmental racism start? What events positioned Chester as the ‘nations’ worst case of environmental racism?’

Chester was once a flourishing ‘boom town’, according to Dr. Marilyn Howarth of the Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology. During the 1960s, it was host to multiple manufacturing centers, namely Sun Ship, Scott paper, and Ford Motor Company. The site of the town along the Delaware River was attractive for industries that heralded the surge of the middle-class population. Chester boasted a good educational system, department stores and was a major music venue that hosted jazz concerts and live theatre. But the city’s heyday was short-lived.

A sign that has greeted people entering the city since the 1920s, ‘What Chester makes, makes Chester’ now serves as an apt parody for the flared pollution that characterizes the city today

A sign that has greeted people entering the city since the 1920s, ‘What Chester makes, makes Chester’ now serves as an apt parody for the flared pollution that characterizes the city today. Chester experienced economic and demographic restructuring after World War II due to technological advancements and competition from abroad that led to massive deindustrialization. The shift of the city’s core industries offshore follows the common trend of industries relocating for factors such as cheap labor and land values. Also typical of other cities in the American Rust Belt, the subsequent collapse of the economy and the deficit in manufacturing jobs led affluent residents to move to the suburbs, leaving behind the poor minorities.

The evacuation of manufacturing jobs led to the transformation of the demographic make-up and ‘white flight’ out of Chester. Coupling the concept of ‘white privilege’ to ‘white flight’ as geographer Laura Pulido has demonstrated expands conventional understandings of racism. Namely, white residents secure relatively cleaner neighborhoods, through processes of suburbanization and decentralization. White privilege, which is embedded in our social, economic, and political system, thus reinforces discrimination between ‘whites’ and ‘nonwhites’ in creating forms of racism that are geographically distinct. The resulting segregation between whites in suburbs and nonwhites in the city core contributes to environmental racism through the uneven distribution of and exposure to toxic air, polluted water, and other environmental hazards. This phenomenon, termed the ‘spatiality of racism’ applies to Chester’s process of deindustrialization, urban disinvestment, and demographic change that characterize its landscape of environmental racism.

Racism and its consequences occur across multiple scales – individual, institution, society, and global. The concept of ‘spatiality of racism’ challenges us to look beyond Chester’s polluting activities of a single facility and instead address the larger industrial zone in its relation to the suburbs and the inner city. Meanwhile, a historical perspective helps us recognize the racialized process of suburbanization that created these regions in the first place. The clarification of the relationship between industrial zones, suburbs, inner-city, and race then becomes primary to understanding contemporary patterns of environmental racism.

Attention to Chester’s broader history of class inequality and racial segregation implicates instead a suite of intersecting drivers of environmental racism

Most studies on Chester’s environmental racism till date have been conducted using inadequate scales of analysis – mainly by focusing on the polluting facilities and its immediate harm on the air quality. Accordingly, we encourage moving beyond those limited conceptions of scale and a narrow understanding of racism to identify linkages within the spatial units of Chester’s industrial zone, the suburbs, and the inner city that produce a toxic urban landscape. Where standard narratives blame the siting of toxic facilities as discreet acts of individual racism, this approach draws attention to Chester’s broader history of class inequality and racial segregation which implicates instead a suite of intersecting drivers of environmental racism.

Beyond environmental racism

Two dominant narratives have constrained the environmental racism discourse. As geographer Malini Ranganathan argues, environmental racism is often reduced to matters of individual intentional acts, in which a few ill-minded people misbehave in an otherwise race-neutral society, while race itself is assumed to be randomly correlated with the siting of toxic facilities. Both narratives constrain our thinking and treat racism as an unfortunate outcome of personal disposition. Accepting race as a random correlate of hazardous facility siting makes it difficult to raise questions about the broader structures that direct the siting process. Even when there is no intent to discriminate in the siting process, the market forces that trap ethnic minorities in such locations, for instance, should not be seen as ‘race-neutral’.

In the case of Chester, past policies of housing segregation remain intertwined with contemporary decisions about siting hazardous facilities. Zoning decisions made in the past to racially segregate residents and concentrate industries in African American communities have present-day effects. Even though the present decisions to place facilities in industrial zones may appear race-neutral, the outcomes discriminate against minority populations. This is so because polluting facilities end up in low-income African American communities due to the past discriminatory decisions to situate industrial zones around minority communities. The low-income, predominantly African American community in Chester is thus disproportionately subjected to industrial pollution and its attendant health impacts. This is an example of what Joe R. Feagin and Clairece Boojer Feagin term ‘side-effect discrimination’, where discrimination in one area reinforces discriminatory outcomes in another even while the siting decision itself has no discriminatory intent. Identifying the factors that create disparities in the distribution of polluting facilities is critical towards understanding who is responsible for environmental harms and what can be done to reduce them. Towards this end, more attention needs to be given to understand how housing market policies confines people of color to hazardous areas and if those actions qualify as racist or discriminatory.

The toxic pollution of Chester and its myriad bodily effects on poor and minority residents serve as a vivid example of Rob Nixon’s concept of ‘slow violence’. This idea captures the gradual environmental harm that affects marginalized residents, which, unlike spectacular disasters like Chernobyl or Hurricane Katrina, is usually difficult to witness and measure. Slow violence has both spatial and temporal components. While it welcomes attention to immediate destruction within a particular space, it also instigates us to delve into the past to uncover the structural processes that allow hazards to accumulate and defer their damage over time.

The Department of Environmental Protection continues to make siting decisions based on the demography of Chester, which it perceives to be politically incapable of mounting strong opposition

So, why do toxic facilities continue to flourish in Chester? The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) distributes permits based on a ‘decision analysis’ that largely denies the cumulative impacts of past emissions in Chester and the active permits that enable pollution today. Deindustrialization decimated land values, which made it attractive for toxic plants to assume permanency on cheap land. The DEP continues to make siting decisions based on the demography of Chester, which it perceives to be politically incapable of mounting strong opposition. Recent environmental justice campaigns move beyond race to engage with people affected by such encroachment due to lack of economic presence and political power. This encourages us to move past previous debates about whether race or class is a better predictor of where toxic facilities are designated. The case of Chester shows how historical, political, social, and economic specificities intersect to produce a toxic landscape. Future research on these components would not only enable us to understand how such factors influence facility siting but also their implications for collective struggle and resistance.

Making the gradual harm visible

What might make the gradual harm of residents more visible and thus more amenable to change?

The evident forms of ‘slow violence’ in Chester serve as a layered burden of poverty, environmental pollution, political repression, and inadequate education, which makes community activism and resistance challenging. While media narratives sensationalize Chester’s pollution and toxic air, it fails to initiate conversations about the structural discrimination inherent in the historical developments that Chester has witnessed. To grapple with a proper understanding of environmental racism we suggest moving past purely descriptive narratives and those that narrow the understanding of racism to individual acts. The recognition of the scale at which racism is prevalent and its interlinkages with the inner city, industrial zone, and suburbs then become instrumental for a broader conceptualization of racism.

While we attach importance to the historical developments that shaped much of Chester’s toxic urban landscape, we also recognize the influence of past discriminatory housing policies on present-day facility siting in Chester. Documenting and narrating communities’ toxic experiences also provides a defined shape to the otherwise formless and invisible threats to residents and thereby helps confront slow violence.

Towards this, Zulene Mayfield, a longtime resident of Chester, has been steadfast in her battle against the facility siting around minority neighborhoods. Active since 1992, her grass-roots organization, Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living (CRCQL) has made strides to fight against the issuance of new chemical permits to facilities with occasional successes. Additionally, Dr. Howarth and her colleagues are conducting a health study to investigate health outcomes among Chester residents. Besides the health study, they support community members in approaching the DEP to investigate the industries’ flawed practices. They also collaborate with the Chester Environmental Partnership to sustain community’s voice among regulatory agencies. According to Dr. Howarth, a monumental success for Chester would mean a fair regulatory process that decreases emissions and allows companies to operate in a manner that is not detrimental for its residents. Towards this, spreading awareness through public education, distribution of community resources, and monitoring indoor and outdoor air quality has been their other notable success to date.

A bigger question, however, remains – how can we interrupt the pattern of toxic harm done to African Americans in Chester? Thinking along the concepts of white privilege and slow violence – however, it makes sense for us to stop questioning why an incinerator was placed in an African American community but instead question why and how were the whites able to distance itself from the pollution in Chester? Moving forward, is it possible to correct the ‘flawed regulatory practices’ of the DEP in Pennsylvania which according to Dr. Howarth is an ‘extremely industry-friendly’ state? While temporary protective fixes of air filters and cautions about venturing outdoors are in place, when can we finally begin to think about institutional fixes that bring justice to residents who have aged breathing toxic air in the long-neglected city of Chester?

Veronica Gomes is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia. Her research focuses on the study of residential segregation and health outcomes of minority populations with a focus on understanding neighborhood-level exposures, community specific perceptions of health and the spatiality of deprivation.

Kimberley Thomas is an environmental social scientist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University. She takes a political ecology approach to questions about environmental justice, human vulnerability to hazards, and the multi-scalar politics of resource governance.