by James Banks

I remember when I was young, I wanted to go on a road trip real bad. My mom said, “Maybe next summer”. But I wanted to go that summer. So she said, “We can’t go on a road trip, but we can pretend.” I was six years old, so I was okay with that. My sister was nine years old and she knew better. But what was she going to do? And my dad got into it.

They got us sitting in chairs next to each other. And Dad started out driving, and he described us driving down Chase toward Avocado, and then getting on the 94. We were taking the scenic route. There were giant metal dinosaurs. I knew which kind of dinosaurs they were. And then we caught up to the 8 and drove down the twists into the Imperial Valley.

It was beautiful there, hot, humid, and beautiful, everything irrigated. There were giant date groves, and fields full of alfalfa. We stopped in El Centro to get some ice cream, my Dad pulling over and all of us unbuckling and getting out and walking over to the refrigerator.

We got back in the car. Mom was driving. She was the only one who could take over because me and my sister weren’t old enough to drive.

We wanted to play music, so Mom pulled over and Dad hopped out of the passenger seat and got the boombox from the garage and dusted it off and we listened to the radio and Dad’s old CDs.

It was a pretty good trip. We went for four hours and then we got off at our motel room in Tucson.

—

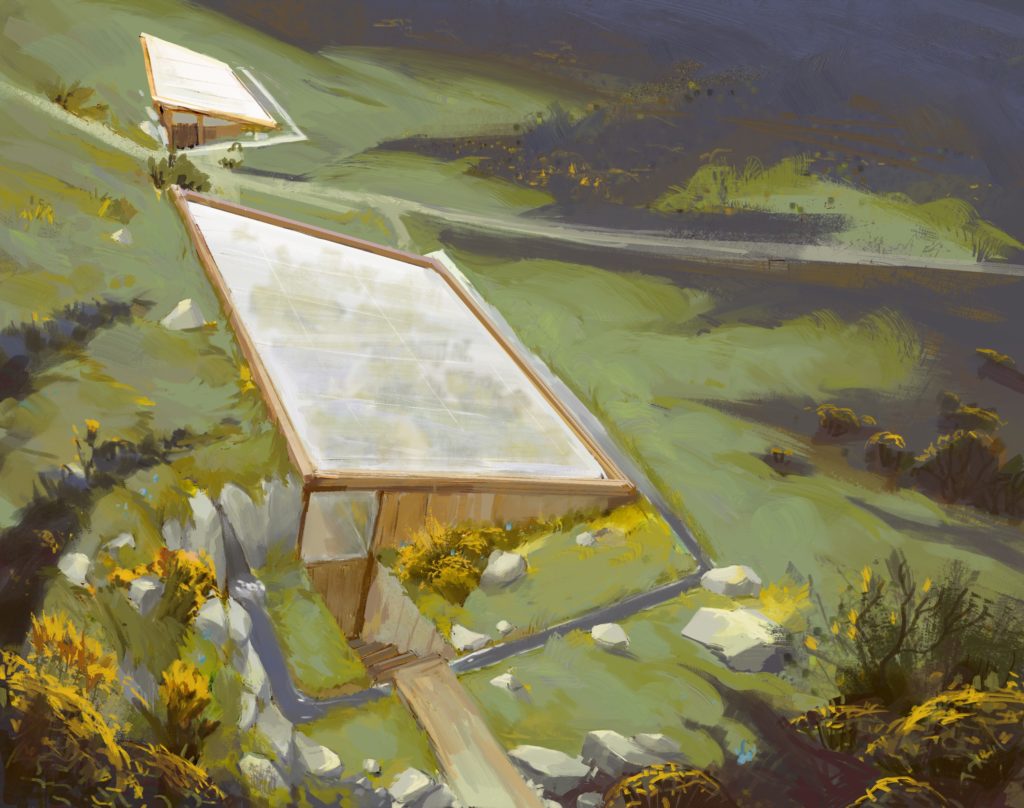

I remember when I was in college. We lived in the old house in El Cajon. I walked to the El Cajon Transit Center to take a trolley to SDSU. It was about a mile or a mile and a quarter walk. I remember during that time my mom invited a mother and her son to live with us. The mother lived in my sister’s room, and the son slept in mine. They were from the Imperial Valley. There used to be a big salt lake in the Imperial Valley called the Salton Sea, but it dried up for the most part and there were terrible dust storms from the exposed lake bed, and most people left around the time I was in college.

I remember the son being a bully, and I remember how finally I couldn’t take it anymore. I couldn’t get any sleep with him around. I think he thought that since he and his mom didn’t have any place to go, and we were good people, that we would have to help them, but finally we confronted them. He talked his mom into leaving instead of him changing. I heard she got a job at the Viejas Solar Farm, and he started school at the community college out there. I remember one day she came back to visit and she was talking about her son. She was really worried because he had a gambling problem. All his money went to the casino.

It’s a sad story. Some years later they shut down the casino and remodeled it, and they use it for different things now.

—

I remember one time there was a big protest. “No More Ecosocialist Nightmare!” said one sign. Another said “War is Peace. Slavery is Freedom. Poverty is Wealth.” They were protesting in favor of personal liberty. They said that climate change might be bad, but so would an “Orwellian sustainability”.

The political science professors had theories of how to not have Orwellian sustainabilities, but I only had one political science class, so I wasn’t taught them. One of my friends was a poli sci major. He wanted to go into politics. I asked him about it and he said “Basically, it comes down to whether people who end up in power are the kind of people who don’t want there to be Orwellian sustainability. And, whether they’re the kind of people who can carry through that commitment.” I thought there should have been a better answer.

—

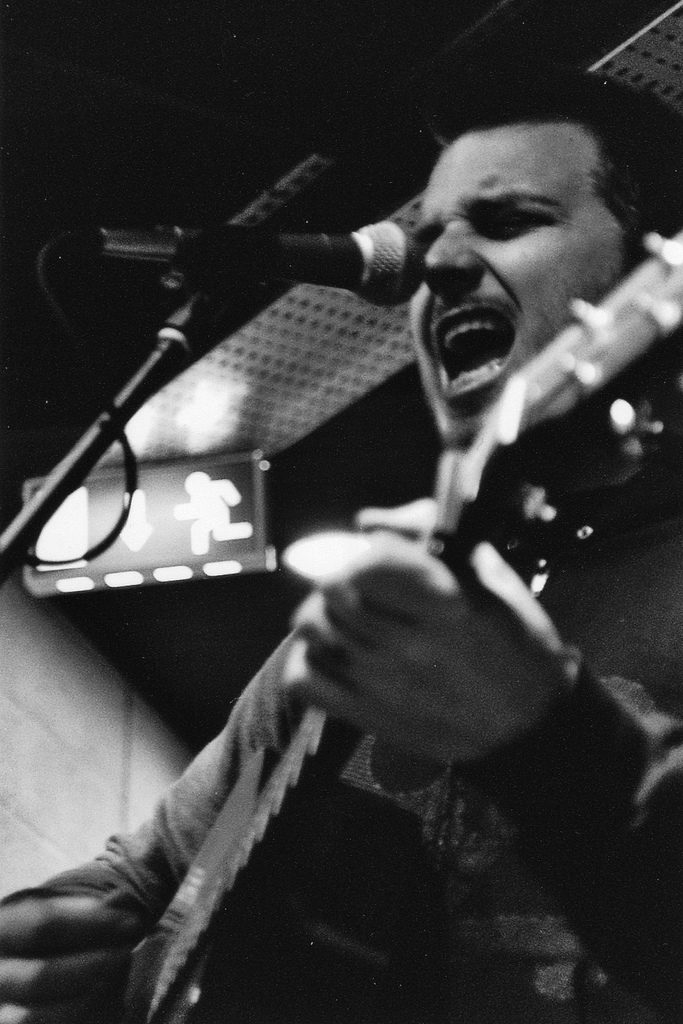

I remember rations. I went to a hardcore concert with my friend once. The singer was screaming about rations, complaining because they didn’t think they needed to be so tight. I also used to go to stand up comedy back then and everyone talked about rations. I think people still complain about rations.

We used to have FFDs (“fasting and frugality days”) where we tried to consume as little as possible. Usually on a day we all had off. We got out the CD player and put on some Indian music and we would sit there with our stomachs digesting themselves (or at least that’s what it felt like). We would groan and make jokes about being hungry.

—

I remember my sister moving out to get married to her boyfriend. First they moved into the master bedroom of a house in Rancho Peñasquitos, where the widower moved to the downstairs bedroom. They had to work some shifts as caregivers to lower the rent. Then after he passed on, they moved into a house with another couple they were close to, and the two couples started to have kids, and the kids grew up in one little mob.

—

I remember trying to find people to fit in our house. We needed people we could really trust. It took a few years, but I finally felt like one of my friends could share my room. We adopted him into our family, but not legally. My sister’s room was free by then so we invited some older people from church to stay there. They were okay for me and my friend. But then they had to move to a nursing home after about five years, and we had to find someone new. Mom and Dad were also getting older, so they called up some old friends in another state, people they “never got to see enough these days”. And they agreed to move in. So my parents and their friends were having a good time all the time, but it was too much for me and my friend, so we started going out more.

—

There were a lot of people who didn’t work, or didn’t work much. I remember spending whole days walking through El Cajon, looking at the people walking around. There were some days I got real bored, and there were two days to get through before my next shift at my job. I remember some people getting into mischief because they were bored, and that bothered me, so I decided to try to talk to those people. I would tell them about imaginary places, and if they were bored enough, they would listen.

—

I remember one time we did take a road trip through Imperial Valley. There were big signs that said “Dust storms likely next 45 miles.” We saw an old house and wondered if anyone lived in it.

—

I remember rent being low. But water was expensive. A lot of electricity went into the desalination plants.

When I was in college, some friends and I went out trespassing one night and ended up in the salt ponds at the end of San Diego Bay. We walked along the paths at the edges of the pond. Then we saw something lit up a little in the dark, a huge building. “Is that the desalination plant?” we wondered. When we got close enough to read the sign, we were close enough to be seen by the guard who ran us off the property and warned us harshly to never do that again.

—

I remember when some people set fire to someone’s mansion. They said it was for crimes against the environment, for hoarding resources. The conservatives said, “I don’t know why you would burn down a house to protest resource waste.”

Looking back, I think the people who burned down the house had a point, and the conservatives had a point. How can you stop someone without hurting them? And how can you hurt people without destroying something good? I can’t think of how to get some people out of their mansions, but maybe we can prevent people from becoming the kind of people who live in them, without burning anything down.

—

Our neighbors never took anyone in. After the son left it was just the mom and dad. “We’re fine the way things are”, they said. They were nice neighbors, always brought us something good at Christmas-time.

Eventually my friend and I started sleeping in tents in the backyard and my parents let a couple of my cousins have our room. When it rained, a few times a year, we slept inside in the living room.

I think I’m okay with my neighbors not taking anyone in. Some people can do some things, other people other things.

—

I remember when the last homeless person got a place to stay. It was on the news. I heard that some of them messed up the places they moved into, because they weren’t used to having their own property. I guess some of them had personality issues too. The city of San Diego had a call for volunteers to be their friends, although they called it something other than “friends”. You can’t hire people or force people to be friends, was their thinking.

—

I remember one night my friend was making too much noise getting into his bed and I said vicious things. I needed my sleep and I had been around him too much anyway. So my parents sent us out to have vacations at separate hotels. We each had our own room in the hotels we stayed in. We came back and found out from each other that both the hotels were on the beach and had amazing views. They were both in Mission Beach. We laughed when we realized that it wouldn’t have been hard for us to have run into each other by mistake, down there on the boardwalk. He said “That would be a terrible mistake, to see someone when you shouldn’t”.

—

I remember when my father died, and then a few years later, my mother. My sister and I sold the old house in El Cajon, and I left San Diego County for good. I left everyone behind. Time to try something new, I thought. My friend waved goodbye to me.

I took a train to Chicago and then one to New York City and then one up to Maine. On the opposite end of the country, I got my own place to stay. But there didn’t seem to be enough people inside my house, and I didn’t know anybody to live with me. My friend had to stay in San Diego. But I met a nice woman and we settled down, so that’s what kept me up there, for many years.

—

These are all some things I remember. And what will you be remembering, as you live the life ahead of you?

—

James Banks lives in San Diego, CA and has written fiction and non-fiction about the sustainable future, being lost, development, trust, and (anti)romance. Website: 10v24.net

Photo credits:

Photo one: Calexico New River Committee / public domain / https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nrborderborderentrythreecolorsmay05-1-.JPG

Photo two: by Dave Shearn / CC BY 2.0 / https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dustin_Kensrue.jpg

Photo three: by Pacific Southwest Region USFWS / CC BY 2.0 / https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Panoramic_aerial_of_completed_Western_Salt_Pond_Restoration_Project!_(6967928908).jpg