Sergio Ruiz Cayuela

I will tell you something about stories,

[he said]

They aren’t just entertainment.

Don’t be fooled.

They are all we have, you see,

All we have to fight off

illness and death.

Leslie Silko, Ceremony (1977)

Developing a subaltern consciousness

The hazard does not disappear by sweeping the dust from their balconies and shutting the windows.

For the Can Sant Joan neighbors pollution is not anymore imagined as a visible dust cloud with clearly defined boundaries from which you can escape. The hazard does not disappear by sweeping the dust from their balconies and shutting the windows. The community perceives pollution as scattered around the neighborhood in multiple and mostly invisible forms. From the thick smoke clouds that are still released from the chimneys of the LafargeHolcim cement plant to the invisible dioxins and furans. From the rain that pours loaded with heavy metals to the tomatoes that were once grown in chemically contaminated soil. Pollution is not discrete anymore, but a continuous entity that not only impregnates everything but trespasses macroscopic physical boundaries. People in Can Sant Joan have developed a consciousness of their bodies’ constant interchange with their environments. Thus, the very place where they live their everyday lives—an environment that has been infected with hazardous toxic pollution for decades—has become a threat for the community members.

During years of tireless struggle against the cement plant—and other sources of pollution—Can Sant Joan neighbors have realized that they are fighting a very unbalanced battle. It is not just a factory that they are opposing, but a whole economic system that fosters inequalities and prioritizes growth before well-being. Political and economic elites dispose of the most marginal, powerless communities in order to increase profit and reinforce their social dominance. The Can Sant Joan community has become aware of this dynamics through first-hand experience. As a neighbor puts it: “they thought it was going to be very easy to pollute and kill a community of poor working-class people, but we fought back and won’t stop until the cement plant is shut”. By recognizing their marginal position—in economic, political, and social terms—and acknowledging lack of autonomy and political representation as the main shortages in to order leave marginality, the community has developed what is called a subaltern identity.

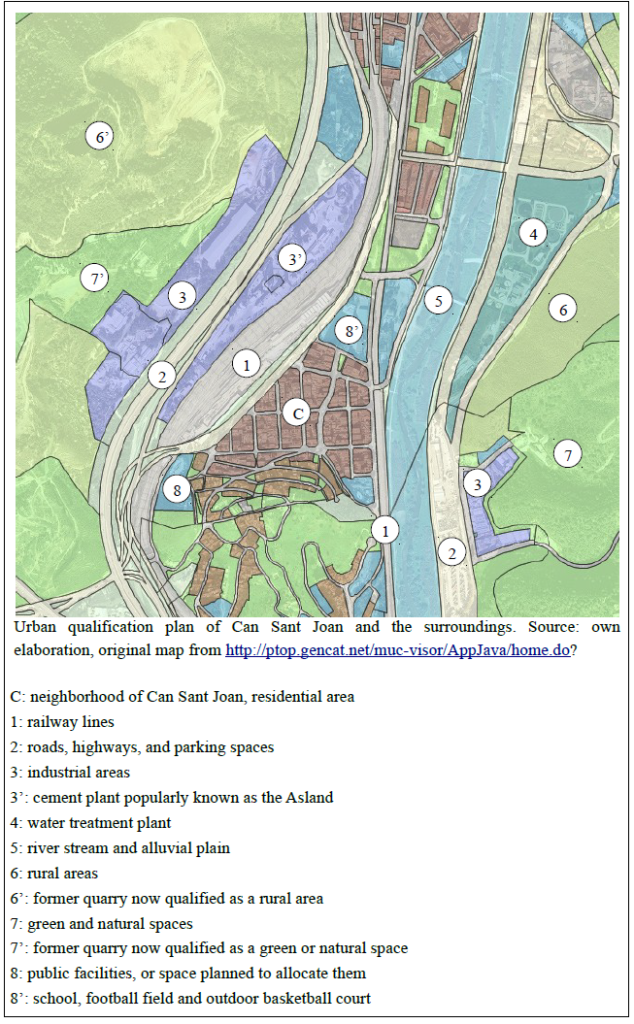

Can Sant Joan has been deliberately burdened with abnormally high environmental impacts.

The leakage in 1984 of the Cerrell Report, commissioned by the California Waste Management Board to a consulting firm, shed light on the relationship between subalternity and environmental health. The report sought to define the type of communities that were less likely to resist the siting of locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) in terms of race, income, class, gender, or religion. It proves that many times the placing of LULUs is deliberately based on political criteria. Since its creation, Can Sant Joan—a neighborhood that was born as a settlement for mainly unskilled migrant workers at the cement plant and the railroad track—has been incrementally burdened with polluting industries and infrastructures. This reinforcing pattern has created a vicious circle: the more LULUs were placed in the neighborhood, the less desirable it was to live in it. As a neighbor described: “people didn’t come to live here because we chose so, but because housing was cheap. Where else could we go?” Thus, Can Sant Joan has been deliberately burdened with abnormally high environmental impacts that pollute the environment, threaten the health of the community and, in short, make the area a sacrifice zone.

The subaltern in Can Sant Joan are contesting this image of the passive and defeated subaltern through their resistance.

The situation for communities inhabiting sacrifice zones is often represented as hopeless. But the subaltern in Can Sant Joan are contesting this image of the passive and defeated subaltern through their resistance. The best way to understand why and to learn about the community and its struggle against waste incineration in the cement plant is, in the fashion of what the Toxic Bios project proposes, through the personal story of a neighbor who has been deeply affected by living in such a polluted environment. It’s time for the subaltern to speak!

Toxic storytelling: Manolo Gómez “el zapatero” (“the cobbler”)

I am 74, I was born on January 24th 1943 in a little village in Granada called Benalúa. All my family members were republicans. Two of my uncles were distinguished soldiers during the Spanish Civil War and they went to France into exile, but Franco’s regime had a deal with Gestapo and they were still prosecuted during those years. My family was part of the lowest class. I saw a man starve to death at my doorway, I will never forget that. He came begging for some food while my mom was cooking a stew. But the moment he took the first bite, his body had a bad reaction and it was as if he had been struck by lightning. I came to Can Sant Joan when I was 16 because my family was being punished extremely hard by Francoist local authorities in Benalúa. They were making our lives impossible and we had no possibilities to survive there. I didn’t come to Catalonia voluntarily, I was expelled from my land. I went to the school of Franco until I was 16, ruled by the Catholic church, very Catholic. When I was 9 years old I started working and I combined it with school. I was working at a projection booth in a cinema, because I am a qualified projectionist. Then I also started working as a cobbler. So, during the daytime I supplied footwear to my neighbors and during the nighttime I entertained them. Since I arrived in Can Sant Joan I joined the neighborhood association and I was involved in the struggles. I was also member of a revolutionary left political group during 15 years, in the 1960s and 1970s. We fought the regime and our main goal was to kill Franco. I don’t know if I would call myself an environmentalist… definitely not an “abstract” one, but maybe I could be called a radical environmentalist.

I don’t know if I would call myself an environmentalist… definitely not an “abstract” one, but maybe I could be called a radical environmentalist.

The current Can Sant Joan neighborhood was born in the 1960s migration boom. We all came from different places, we didn’t know each other, but there were a core of people who started bringing the neighborhood together and convincing ourselves that we shouldn’t accept our living conditions. We were always the most working-class, leftist, united and open neighborhood. We never had problems with anyone, even now that people from abroad keep coming here. We are an open neighborhood. The most tenacious neighborhood has always been Can Sant Joan, and it’s not me saying that, but all the other neighborhoods in Montcada. The neighborhood has been changing for the better during the years by dint of all the struggles that the community has carried out. But nobody ever gave us anything for free in this neighborhood, everything we have achieved has been through constant struggle. The Can Sant Joan neighborhood is everything to me, it has given me everything that was denied to me in other places. I always said that the day that I retire I will keep working for the neighborhood. And after 60 years working, fixing shoes for three generations and screening movies at the Kursaal (the former cinema of the neighborhood, that was abandoned for 26 years and then turned into a popular auditorium after a strong mobilization, author’s note), here I am. I am very grateful to the neighborhood. Then we started to build a real community and today this is not just a neighborhood but a close community. We have a theater association, a poetry group… we were even able to bring the Basque poet Silvia Delgado to the Kursaal. I put a lot of effort into it, because I love poetry. Even if most people work in the city, there is a core group that always organizes public events. Especially around the school and the parents’ association, but also the storekeepers’ association organizes a handicraft fair, we also have a group of gegants i capgrossos, the castellers… (groups that perform different acts related to Catalan culture, a.n.), everyone is involved!

I usually feel a very unpleasant smell from the cement plant and from the sewage treatment plant that is across the river. It is terrible, it is massive, the smell that we feel from time to time is suffocating. In Can Sant Joan there are many people with respiratory problems, especially cancer. This is our biggest problem right now in the neighborhood. And all these sick and deceased people are a consequence of the toxic environment we live in. It’s not just me saying that, it’s everyone here. I have a chronic disease—asthma—because of the cement plant. I have claimed that on TV, on the radio, and wherever I can. I will repeat it 30,000 times if needed: living under that chimney for 74 years is terrible. I don’t even know how I’m still alive.

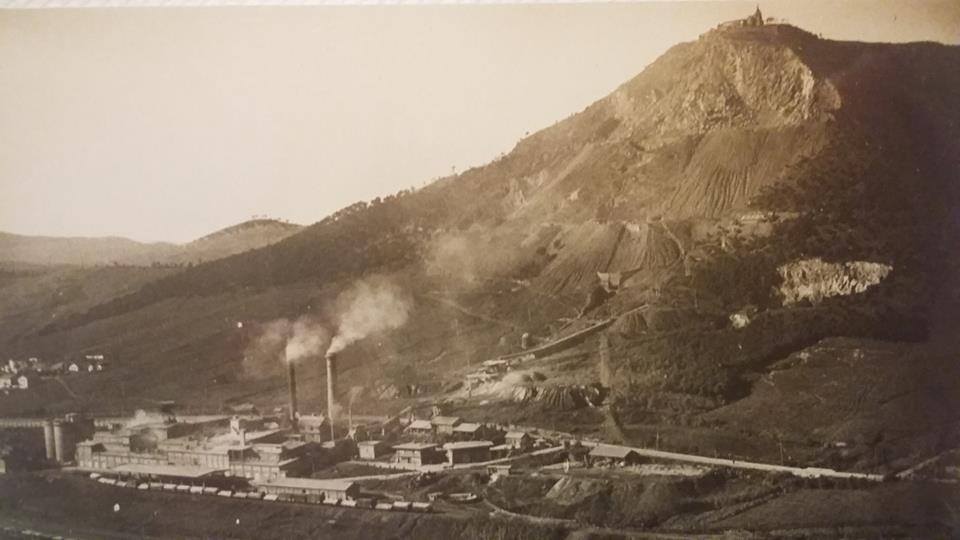

The cement plant, which is about to turn 100 years old, was first owned by the Asland company. It was ruled by the Catalan bourgeoisie, who started the company in Castellar de N’Hug, but they didn’t find enough raw material there so they came here. Another reason was the railroad, because they built a branch that connected the cement plant with the main railroad line and they were able to transport their products more efficiently. I still remember years ago that every noon there were terrible explosions in the quarry. Every day at noon a siren would sound off and then a huge blast would follow. Enormous dust clouds would come off the hill, that once was about double the current height. We had to hold the windows with our hands or otherwise they would just blow up. That was every day at 12 a.m. during the 1960s… Moreover, there was a small chapel on top of the hill, owned by the clergy, who made a pontifical Bull and gave the chapel for free to the Catalan bourgeoisie. They just tore it down in order to extract more material. Later on the multinational company came and bought the business, and they still own it. There used to be 40 or 50 regular Asland workers at the neighborhood, and a lot of indirect workers as well. Most of the people at the neighborhood used to work either for the Asland or the Renfe (the railroad company, a.n.). A few years ago we went through all the people we knew from Can Sant Joan who used to work at the Asland and we found out that all of them are already dead, from cancer. There’s nobody left. Currently there are barely 30 or 40 workers at the cement plant. They have a terrible technology, they don’t need people anymore. Trucks get loaded and unloaded automatically. The plant only needs a cheap labor force when they do maintenance tasks, but those people are only employed a few days. The company does whatever is needed in order to avoid paying wages.

We know very well that we are getting into the heart of capitalism, but we are not scared.

The Asland (the cement plant is still nowadays popularly known as Asland, in reference to the former owner, a.n.) has a strong presence in the neighborhood, very strong. These splendid factories know how to buy people, and some people like being sold. The managers even tried to bribe us (us refers to the neighborhood association, a.n.) when we started to say that they shouldn’t start burning waste, that we’d had enough. After 30 years suffering a waste incinerator (the first urban waste incinerator of the Spanish state started to operate in Can Sant Joan in 1974. See next paragraph for further clarification, a.n.) we already knew what was going to happen. They called me and my mate (both members of the direction board of the neighborhood association, a.n.) to the manager’s office, and he asked us what were our demands to stop saying that what they were going to do was dangerous to the people. It was just before they started burning waste. And the Asland also used to have a terrific relationship with the municipality. For example, when the Socialists (in reference to the Catalan Socialist Party, a.n.) were in power they used to organize fireworks contests during the town festival. That costed a fortune, but it was all paid by the cement plant. They even paid the municipal newspaper, which is called La Veu. It used to be financed by Lafarge, you can still see many Lafarge adverts in it. The cement plant also finances all the football teams in Montcada, the chess club, and whoever goes asking for money. The company used to donate 3,000€ every year to our neighborhood association for the annual neighborhood festival. Now the relationship with the municipality seems very different, but we’ll see what happens… Because politicians fear these big companies. We don’t fear them, but politicians are scared because these companies have huge economic power and can buy everything. We know very well that we are getting into the heart of capitalism, but we are not scared.

We already suffered a waste incinerator here, and many people got sick and died because of it. We succeeded in closing that incinerator after a long-time struggle. After that, local politicians assured that waste was never again going to be incinerated in our town. A motion was even signed in 1999 by all the political parties banning waste incineration in the Montcada i Reixac municipality. And when 10 years ago we learned that they were going to start that atrocity again in the neighborhood, we sounded the alarm. I had already been involved in the struggle against the waste incinerator, which was the first one in the whole Spanish state—like a pilot project. We organized a huge demonstration when there were no highways getting into Barcelona yet, and we blocked the only Northern access to the city. We were a buttload of people from the neighborhood, we walked from here to the cement plant and we came back. It was a great day! We also mobilized against the big chimney at the cement plant, which was releasing huge dust clouds 24 hours per day. We forced the Asland to install the first cement filters and the amount of dust decreased. And from those past struggles comes my current involvement.

We are realizing that this is a common problem, and that everywhere they tell the same lies.

Now I am at the direction board of the neighborhood association, I attend all the mobilizations, I am the secretary of the neighborhood association, and especially, I am just one more in the movement. We have organized demonstrations with up to 3,000 people but there is something even more important. We have been able to raise awareness among the community so when someone gets cancer, and everyday there are more people—especially young—getting sick, they point out to the cement plant and the environment. This is very important. We thought that we were alone in this, but now we are realizing that in the Spanish state there are 36 cement plants and the same thing is happening everywhere. And not only in the Spanish state but also in Europe, in America… They are perpetrating atrocities. They are ruining our lives, poisoning our water and air… and nobody can live without water and air! It is terrible and they are perfectly conscious of what they’re doing. They are criminals. And we are realizing that this is a common problem, and that everywhere they tell the same lies. The politicians, the cement companies… they say the same thing everywhere! They are scoundrels, criminals. We are ruled by criminals. We have had some problems with the local authorities. Not with the new mayor, but with Socialists and Convergents (referring to politicians from the Socialist Catalan Party and from the nationalist electoral alliance Convergence and Union; a.n.) we had some problems. I was prosecuted by the local police. We were calling the neighbors with a megaphone for an assembly, when the mayor sent the police to frisk me. The officer, who was a good person and a casual acquaintance of mine, told me: “look, I’m sorry, but I was ordered to frisk you and ask for your documentation”. But they could not find anything against me.

There are experts of many kinds in this country! I call some of them mercenaries for hire. There are also very honest and professional people, practitioners and scientists who have dared and still dare to talk against this scum. But others… there are some mercenaries for hire and those are horrible. There is a mercenary called Domingo, from the Rovira i Virgili university who says that it is more dangerous living beside a highway than under a waste incinerator. And these mercenaries are those who are hired by the public administration and they make their reports to measure. But we have also been helped by many experts, I could tell you a long list of names. I think they also take something positive from the experience, and they are being very helpful for our movement. Nobody dares to contradict them. And they collaborate in a completely unselfish way, they just fight for the health of the community. There was one, though, whose name I prefer not to reveal, who got scared and gave up. He helped us a lot, but there was a huge dispute with the cement companies and he got scared.

Subaltern voices and resistance in guerilla narratives

Manolo’s story shows that sacrifice zones are not only geographical places, but also subaltern human—and non-human—bodies. The toxicity concentrated in these sacrifice zones—whether geographical or organic—is not only embodied in the obvious ecological way, but it is spread beyond. Toxic stories that deliberately distort reality develop in order to boost ignorance about the real environmental health impacts, in a process that constitutes narrative violence. Sacrifice zones thus carry a double burden: they are subjected to accumulative environmental impacts that harm humans and non-humans, and they are usually invisibilized in official narratives. Concerns about narrative violence are easily found in Can Sant Joan, where the neighbors bitterly complain about the wide presence that the cement plant has historically had in local press and municipal leaflets, and where the Asland is portrayed as a valuable contributor to the Can Sant Joan community.

Storytelling can become a powerful weapon to sabotage the mainstream toxic narrative and occupy it with counter-hegemonic knowledge.

But above all, Manolo’s autobiography shows how storytelling can become a powerful weapon to sabotage the mainstream toxic narrative and occupy it with counter-hegemonic knowledge based on physical and cultural experiences of everyday life. It can be compared to such an iconic image of sabotage and resistance as the monkey wrench in its twofold purpose: on the one hand it can be used to undermine the mainstream narrative, and on the other hand it can be used in a constructive way in order to build autonomous spaces where the subalterns take back control of their stories and their bodies. The very action of the subaltern telling their own stories of toxicity—described by Armiero and Iengo as “guerrilla narrative”—is loaded with political meaning, as they decide to reject the passive role that they have been given in the mainstream narrative. This kind of toxic storytelling has the power to bring together subaltern communities trapped beyond mainstream concern and redefine environmentalism towards a broader and more inclusive movement that eventually influences political agendas.

Sergio Ruiz Cayuela is a Catalan scholar-activist and Marie Skłodowska Curie PhD fellow at the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Coventry University. His research interests include alternative environmental movements and the political potential of the commons for empowering subaltern communities.