by Vijay Kolinjivadi

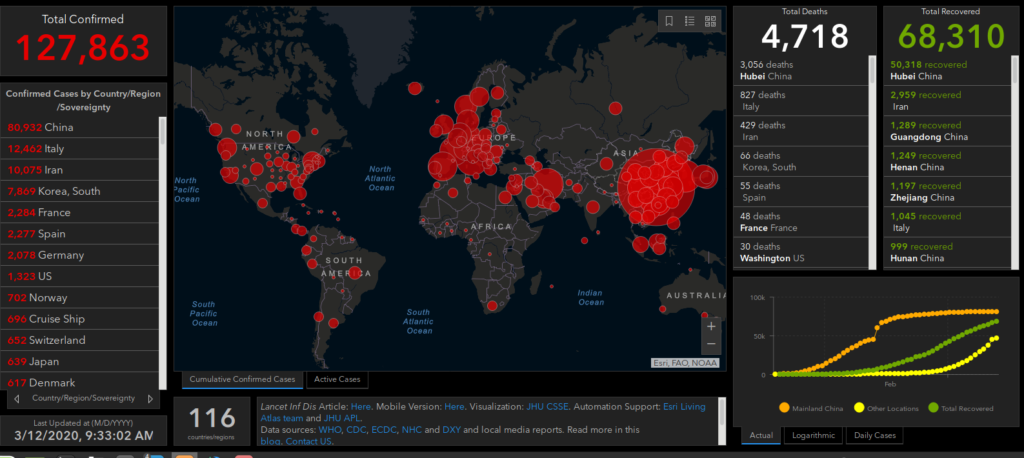

In late 2019, a novel coronavirus (SARS CoV-2) emerged from a wet market in Wuhan in the province of Hubei in China. At the time of writing, it has resulted in cases approaching 1 million and the deaths of over 42,000 people worldwide. Only a couple months ago, the world was taken aback by unprecedented bushfires in Australia, massive youth movements striking for stronger action to tackle climate change, and a groundswell of protests across the world demanding greater democracy, an end to state oppression, and against debilitating economic austerity in places ranging from Hong Kong, to India, to Chile, respectively.

In the midst of these events, COVID-19 felt like it came out of nowhere. The situation (and potentially the virus itself) is rapidly evolving, has taken world governments by surprise, and left the stock market reeling. Its emergence, however, makes self-evident the fault lines in global production systems and the ultra-connectivity of our globalized world. Like climate change, it affects everyone (ultimately), but unlike climate change, it occurs at a much faster rate and more severely impacts the most economically vulnerable, who cannot afford or have the possibility to engage in social distancing. Governments are walking on a tightrope, a balancing act between ensuring public safety and well-being and maintaining profit margins and growth targets. It’s the very same dilemma as climate change- just occurring at a faster rate, arising everywhere, and obliterating the possibility to ignore it and think about it later. In fact, one may argue that the pandemic is part of climate change and therefore, our response to it should not be limited to containing the spread of the virus. “Normal” was already a crisis and so returning to it cannot be an option.

The coronavirus pandemic is like a chunk of ice falling off of a melting glacier. You can see the ice falling, but you can’t see the melting of the whole glacier. Similarly, climate change will keep dropping chunks of ice at humanity well after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. Unless we prioritize a diversity of alternatives that put well-being over growth forecasts and profit, ecological breakdown will forever remind us that societal death is just hanging over our shoulders, always ready to scale down the arrogance of human exceptionalism a peg or two…or ten.

Different, but the same

The ease by which COVID-19 moves through human bodies, and the difficulty of containing it across any human-imposed border is a remarkable case of how humans are dependent on nature, and indeed are part of nature and cannot be separated from it. The study of world ecology for example sees the global and industrial production systems of capitalism as a very specific ecological relationship, without viewing humans as outside of nature. Industrial growth and production systems shape the ecological world and are in turn shaped by new and emerging ecological relations. Industrial production transforms relationships between people and their living and non-living world in ways that resemble a machine. The functioning of every machine requires resources (e.g. land, minerals, fossil fuels) and produces wastes (e.g. a car’s exhaust pipe, pollution, climate change). The consequences of these transformations result in all kinds of effects on life, mostly the loss of species, but also the emergence of new (unwanted) ones like viruses. COVID-19 emerged as a result of industrial production; the very same processes that global economic growth depends so crucially on. The massive-scale wildlife breeding of peacocks, pangolins, civet cats, wild geese, and boar among many others is a $74 billion-dollar industry and has been viewed as a get-rich quick scheme for China’s rural population. The emphasis here is not on the activity of wildlife trading itself (as distasteful as this may be). Rather, it is on capitalism’s relationship to life, which is to convert life into profit in the most efficient way possible, without thinking twice about the consequences, and irrespective of cultural and regional preferences. While out of immediate necessity, the public health focus is on managing the pandemic by flattening the curve of the virus’ propagation to save lives, it is ultimately necessary to understand how this happened and what can be done to prevent it from happening again. This latter question can be answered by seeing the coronavirus as a product of capitalism’s own making.

As socialist biologist Rob Wallace argues in his book Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on Infectious Disease, Agribusiness, and the Nature of Science, increasing land-grabs by agribusiness from industrialized countries has pushed deforestation and land conversion into overdrive for faster and cheaper food production. The transformation of vast areas of land into rationalized production factories provides ideal conditions for well-adapted pathogens to thrive. Any argument that claims pathogens and plagues have always existed across history will neutralize the globalized nature of current land degradation and hyper-connectivity, allowing diseases to spread faster and further than ever before.

The transformation of vast areas of land into rationalized production factories provides ideal conditions for well-adapted pathogens to thrive.

The result of this process, combined with access roads and faster harvesting of non-timber forest products, unleashes once contained pathogens into immediate contact with livestock and human communities. The recent outbreaks of Ebola and other coronaviruses such as MERS for instance were triggered by a jump from virus to human communities in disturbed habitats amplified through animal-based food systems, such as primates in the case of Ebola, or camels in the case of MERS.

The economic pressure under capitalism coerces farmers in any country to cut corners, to rush, take risks, and exploit vulnerable people and decimate non-humans. Any safeguard is considered an obstacle to profit. Yet, somehow like magic, with the COVID-19 pandemic, safeguards in the way of protection for health care professionals, grocery store workers, personal protective equipment, and investment in health research that was non-lucrative just 3 months ago, is suddenly a societal priority. That is, for now; once the pandemic ends, rest assured capitalism has no intentions of keeping at bay. Indeed, it will come roaring back in the form of the most punitive structural adjustment the world may see since the 1980s. For example, The World Bank Group has recently stated that structural adjustment reforms will need to be implemented to recover from COVID-19, including requirements for loans being tied to doing away with “excessive regulations, subsidies, licensing regimes, trade protection…to foster markets, choice, and faster growth prospects.” Doubling down on neoliberal policies which encourage the unrestrained abuse of resources at a time of unprecedented inequality and ecological degradation would be a catastrophic prospect in a post-COVID world. In the discipline of our global economy, “time is money” and any divergence to this discipline means lost profits. The suspension of environmental laws and regulations in the USA is already a frightening sign of what returning to “normal” means for the establishment.

The unrelenting pursuits of economic development are also contributing to 2 degrees or more of global warming. This amount of warming is causing Arctic ice to melt at a breakneck pace, leading to the acidification of oceans, to massive die-off of insects, extreme storms, and rising sea levels. Just as economic growth requires resource inputs and generates wastes like greenhouse gas emissions that have unintended impacts to climate-regulating and other life-support systems, so to does industrial-scale wildlife harvesting generate the conditions for novel and virulent viruses to emerge.

Put differently,COVID-19 is both one and the same as any other ecological crisis (such as climate change) because its emergence is rooted in the same mode of production that has generated all other ecological crises and social inequalities of our times. Climate change plays itself out in different countries based on geographic and socio-economic factors. Similarly, COVID-19 will unfold in ways that reflect the age of populations, the capacity to inform people about and test for the virus, and to have invested sufficiently in health care and protective equipment before and during the pandemic. Finally, while climate change has disproportionate impacts on the economically vulnerable, on food providers (largely women), and on people of the global South, the response strategies to COVID-19 similarly weave through relations of class (e.g. those who are not afforded sick leave), gender (women thrust into roles as care-providers), and race (e.g. scapegoating people from China).

A temporal disconnect

So, if COVID-19 and climate change are one and the same, how are they different? A major distinction has to do with how we perceive time and the temporal effects of both.

A recent study raised an important concern of attempting to respond to climate change on a time scale that is convenient to society (e.g. clocks and calendars) but has absolutely no relation to the time scales of changes we are actually witnessing with climate change. The fact that whole ice sheets melting, 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, and election years appear in unison as “daily news” stories illustrate the temporal disconnect with how society is responding to the changes occurring in our world. It is thoroughly arrogant to assume climate change, like COVID-19, is going to respond to our schedules.

The temporal disconnect of COVID-19 from society’s regularized temporal rhythms of work and leisure is becoming rapidly obvious, grinding the production of global society to a screeching halt within a matter of one week.

The fast progression and potential evolution of COVID-19 clearly defies all of society’s predictable and linear categories of time. Not only is the incubation period for infection hard to pin down, but so is the lag time between infection and when symptoms show up (if they do). Similarly, lockdowns will only manifest in reductions of cases weeks after they are implemented. This is because biological systems do not obey human-imposed rules. The temporal disconnect of COVID-19 from society’s regularized temporal rhythms of work and leisure is becoming rapidly obvious, grinding the production of global society to a screeching halt within a matter of one week. The same temporal disconnect of climate change impacts and its absolutely devastating consequences has not been similarly appreciated, and the consequences of failing to recognize just how fast impacts can take place is just beginning to be understood. For instance, ecologists have long claimed that ecological systems change in non-linear ways. There are thresholds of methane, insect loss, and permafrost melt that, once crossed, are irreversible.

Instead, society must reflect and react in time to the changes it is experiencing. To this extent, COVID-19 can serve as a lesson showing the interconnectedness of society’s impacts and actions on the planet and the immediacy of response required shift our relationships to the world. The lag time between when social distancing measures are put in place and impacts on the reduction of COVID-19 cases once again shows us that biological systems do not obey human-imposed rules. The rapid responses that some countries like South Korea have made to curb COVID-19 offer direction, but also others like Cuba that have developed an innovative biotech industry driven by public-demand rather than profit.

In recent days, comparisons have been made between the number of deaths and suffering that climate change is causing in relation to the current suffering from the coronavirus, and that societal response to the virus has much swifter than that of climate change. Such comparisons are not helpful because they view climate change and COVID-19 as somehow juxtaposed to be two separate “things.” What if both are instead interpreted as by-products of industrial production systems, a tightly interconnected globalized world, and the struggle of modern society to effectively respond to crises it is actually living and experiencing? As Jon Schwarz writes here in reference to society’s stock market love affair: “Think about what we could have done to prepare for this moment, if we’d been less mesmerized by little numbers on screens and paid more attention to the reality in front of us.”

The orchestrated response to COVID-19 around the world illustrates the remarkable capacity of society to put the emergency break on “business-as-usual” simply by acting in the moment. Some argue that the fallout of grinding the system to a halt will have deleterious impacts to billions of livelihoods that we can scarcely comprehend at this stage. This is indeed true. But it is also only true if we go on presuming that the sanctity of squeezing profits out of every ounce of the earth and its people is a harmless process that naturally creates wealth for all. With ecological breakdown and social inequality reaching heaving proportions, society has truly arrived at a crossroads. Time and temporality take on a totally different meaning; there is no longer an attempt to make the world accommodate our needs and wants, but we must immediately accommodate to the world. In contrast, achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, carbon offsetting schemes, incremental eco-efficiencies, vegan diets for the wealthy and similar tactics operate by integrating the “irrationalities” of the world into “business-as-usual.” This will never work. The rapid halt of flights around the world might reduce greenhouse gas emission reductions more than the Paris Agreement or any round of climate negotiations ever could! The fact that CO2 emissions have declined so drastically in concert with the reduced flight demand and manufacturing activity in China provides striking evidence of how economic growth is directly responsible for the existential impacts that 2 and 3 degrees of warming would cause to society.

Yet, despite this clear contradiction, powerful and irresponsible actors are still normalizing COVID-19 through a “keep calm, wash your hands, and get back to work” rhetoric. Indeed, as one market pundit claimed, the loss of stock values is more terrifying than millions of deaths and that maybe “we” would be better off just giving the virus to everybody. It is also important to note that self-isolation and “working from home” are recommended for some, while for billions of workers around the world, simply stocking-up and self-isolating are not options. Millions of migrant workers in India are at risk of starvation due to a 21-day lockdown that has provided no groundwork to account for the precarity of the country’s population.

A window of opportunity for a different kind of world?

Could response strategies to suppress COVID-19 be the impetus to actually respond to climate change, rather than as stop-gap measures to get back to “business-as-usual” as quickly as possible? The answer remains to be seen, but some measures have already been proposed that have been otherwise considered at worst anathema to capitalism, including the nationalization of private enterprise in France and a universal monthly income in the US. As some have argued, COVID-19 presents society with an opportunity to actually respond to climate change through “planned degrowth” that prioritizes the well-being of people over profit margins. This might occur by getting accustomed to lifestyles and work patterns that prioritize slowing down, commuting less, shorter work weeks, abolishing rents, income redistribution from the richest to the poorest, prioritizing workers health (especially for low-wage migrant workers who are substantially more vulnerable in the face of an economic downturn), and relying on more localized supply chains. Yet, the global slowdown caused by COVID-19 is not degrowth; it does not reflect the ethical and political commitment to development predicated on prioritizing well-being over profit. We need a just climate transition that ensures the protection of the poor and most vulnerable and which is integrated into our pandemic response. As warming temperatures continue to melt permafrost at alarming rates, the possibility for even more severe pandemics emerging from the melting ice is a very real risk. Acting on climate change is therefore itself a vital pandemic response.

It can also be facilitated by solidarity networks to support (especially elderly) neighbours in meeting their needs; a genuine “Love in the Time of Coronavirus” moment so to speak. Such groups have already spontaneously emerged in cities around the world, from Seattle, to Montreal, from Wuhan, to Gothenburg and London. In addition to this groundswell of support, now is the time to be bold and demand that our governments serve the interests of people and planetary survival. In our current capitalism-induced ecological and public health crises, this means freezing debt payments to the poorest and ensuring accessible and affordable health care for starters and not letting our governments bail out corporations , while letting everyone else fend for themselves. We’ve heard of “crony capitalism,” well now “corona capitalism” has become a thing. Obviously, the conditions surrounding COVID-19 are not ideal for the just climate transition that is so badly needed, but the rapid and urgent actions in response to the virus and the inspiring examples of mutual aid also illustrate that society is more than capable of acting collectively in time to what it is experiencing.

This piece is a long-form version of a piece that originally appeared in Al Jazeera.

Vijay Kolinjivadi is a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute of Development Policy at the University of Antwerp and a contributing editor of Uneven Earth.