by Aaron Vansintjan

Recently there’s been a wave of arguments defending economic growth from a leftist perspective. People are increasingly reacting to the rise of ‘degrowth’: a diverse movement calling for, among other things, scaling back the total material and energy use of the global economy.

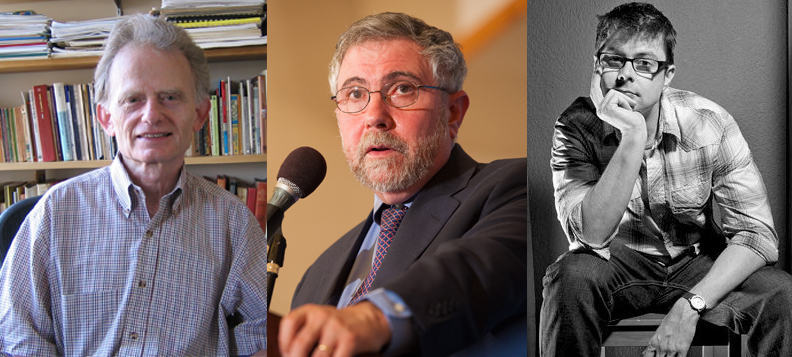

One particularly vigorous example is the work of Leigh Phillips, where he accuses degrowthers—who he claims have become “hegemonic” (file under: things I wish were true but aren’t)—of undermining classic leftist pursuits such as progress, well-being, and strengthening of social services. Similar arguments could be seen in a recent article that appeared in Jacobin Magazine, in which growth was posited as necessary for progress. And Keynesian economists like Paul Krugman have come out against degrowth, claiming that economic growth is actually necessary to address climate change, and lumping degrowthers together with the Koch Brothers, as they both seem to seek to dismantle the state.

When two sides of an argument have a totally different definition of the concept that’s being debated, and if one side even refuses to define it, constructive discussions tend to turn into uncompromising squabbles.

Many of their points have been valid and necessary—serving to complicate the simplistic ‘are-you-for-capitalism-or-a-Luddite?’ narrative. Preaching the benefits of technology and criticizing the current economic system are not mutually exclusive. But there are some recurring problems with these arguments that I want to highlight.

In this article, I argue that definitions of growth are either unclear or constantly shifting depending on the argument. The result is that authors often misunderstand and do not engage adequately with critiques of growth. When two sides of an argument have a totally different definition of the concept that’s being debated, and if one side even refuses to define it, constructive discussions tend to turn into uncompromising squabbles. In an effort to clear up some misunderstandings, I briefly explain what I see as some of the values of the degrowth position.

Growth is everything and nothing: long live growth!

Perhaps the most emblematic—and unfortunate—leftist (or leftish) challenge to degrowth came from Paul Krugman, all the way back in October 2014.

This was a significant occasion. For the most part, mainstream economics ignores ecological economics—a “rogue” field that harbors many of the growth dissenters. But with this article, Krugman brought the challenge out into the open. In his words, the criticism of growth is “a marginal position even on the left, but it’s widespread enough to call out nonetheless.”

Weirdly, Krugman spent most of the article explaining how shipping companies reduced their energy expenditure in 2008 by slowing down their ships. Using this example, his defense of ‘economic growth’ waffled between two very different arguments: that an increase in efficiency can lead to less energy being consumed, and that, theoretically, it is possible to increase the total economic transactions while decreasing total energy use.

With respect to efficiency, Krugman waded into a discussion in which he seems to be out of his depth—other ships have sailed these waters for a long time now. From 19th-century English economists concerned with the decline of available coal to scientists investigating the impact of washing machines, people have long wrestled with problems like the one he raised: how an improvement in efficiency might nevertheless lead to a total increase in energy use. So from the perspective of ecological economics—which has sought to understand how the human economy is embedded within the physical environment—it’s not that hard to sink Krugman’s flimsy argument that an increase in efficiency necessarily increases economic growth while decreasing total energy consumption.

Krugman waded into a discussion in which he seems to be out of his depth—other ships have sailed these waters for a long time now.

What’s curious though about his article is that he not once defined economic growth. This definition remained latent—one can only assume that, whenever he used the term economic growth, he meant the increase in the annual monetary value of economic transactions over time, calculated using the GDP. The article could’ve been a chance for him to show exactly why economic growth is desirable. Instead, he spent most of the article fumbling to find some example that shows that economic growth can theoretically be decoupled from oil consumption.

Granted, if that was the only goal of his article, it would’ve been a good point: a rise in GDP is not the same as a rise in energy use, economic transactions could still take place in a low-carbon economy. The problem is that his argument claimed to go beyond this—seeking to contradict the degrowth claim that, until now, economic growth has been strongly coupled with increasing material and energy use. But his evidence remained purely theoretical, and therefore failed to settle the debate.

This tendency isn’t unique to neoclassical Keynesians—I’ve seen Marxists who’ve suffered from the same inability to explain what, exactly, they mean by economic growth, thereby misunderstanding the call for degrowth.

In Jacobin Magazine, Samuel Farber argues that notions of progress are actually essential for any leftist project. Improvements in technology, infrastructure, and material well-being are crucial for addressing inequality and injustice globally. Fair enough. But then he also explicitly criticizes the degrowth stance:

Many progressive activists today are skeptical of material growth, for ecological reasons and a concern with consumerism. But this often confuses consumption for its own sake and as a status symbol with the legitimate popular desire to live a better material life, and wasteful and ecologically damaging economic growth with economic growth as such.

So here, like Krugman, Farber argues that economic growth is not the same as what he calls ‘material growth.’ And like Krugman, he argues that economic growth is not, in itself, environmentally destructive. But what, then, is economic growth to him? He notes in the following paragraph:

Environmental policies that would make a real difference would require large-scale investments, and thus selective economic growth. This would be the case, for example, with the reorganization of the individualized and wasteful system of surface and air transportation into a collective and rational plan…

It seems that for Farber, defending economic growth is necessary to fight for progressive changes to well-being. What is not clear is exactly why this should be called economic growth. From his examples, there is no quantitative growth—unless you start counting the growth of things like trams and hospitals.

Interestingly, like Farber, many degrowthers might also argue for “more of the Good Things”—for example, increasing health care services, supporting care labor, creating infrastructure for public transportation, and incentivizing renewable energy—but they wouldn’t call them economic growth. Instead, they might prefer to use terms like ‘flourishing’ or ‘sufficiency’ or just ‘more of that good stuff’. They wouldn’t assume that it is total economic growth that allows the good stuff to come into being. Instead, more of the good stuff requires redirecting economic activity to better suit the needs of society—for which the primary ingredient is democratic deliberation, not increased production (social metabolism), larger money supply, or an increase in the transactions taking place in the market economy (GDP growth).

It seems that for Farber, defending economic growth is necessary to fight for progressive changes to well-being. What is not clear is exactly why this should be called economic growth. From his examples, there is no quantitative growth—unless you start counting the growth of things like trams and hospitals.

So there are two problems: the misidentification of what degrowthers are calling for, and a poor definition of economic growth as such. Farber seems to think that degrowthers are claiming that preventing (or reversing) environmental destruction necessitates “less Good Things”. As a result, his argument against degrowth, and for growth, amounts to a bait-and-switch between two definitions of growth: growth of Good Stuff and growth of total economic activity. This failure to define his terms then allows him to mischaracterize the claims of the degrowth movement.

This tactic is heightened to an extreme degree in Leigh Phillips’ recent anti-degrowth polemic, Austerity Ecology & the Collapse-porn Addicts: A defence of growth, progress, industry and stuff. While reading his book I not once got an exact definition of what he meant by economic growth. Growth seemed to include a whole host of things, such as: growth = progress, growth = innovation, growth = increase in well-being, growth = increase in money supply, growth = increase in resource use. He tended to use these interchangeably.

In one instance, Phillips acknowledges this directly:

Of course, one might argue that I’m being far too loose with the terms growth, progress, and invention, which begin to blur here. But then, as well they should, as perhaps what it means to be human is to invent, to progress to grow. To constantly strive for an improvement in our condition. To overcome all barriers in our way.

As far as I could figure out, the logical reasoning here goes as follows:

Degrowthers argue that infinitely and exponentially increasing economic growth is bad for humans and the planet. But economic growth leads to Good Things as well. Therefore, degrowthers are against Good Things.

Phillips denies degrowthers the ability to realize the most basic fact: more good = good, more bad = bad. And if growth is simply Everything That Is Good In The World, it becomes a hard thing to argue against: we’ve reached a conversational impasse.

The problems with muddling the definition of growth come to the fore when Phillips tries to argue, in contrast to Naomi Klein’s recent book, that degrowth and anti-austerity are incompatible: “Austerity and ‘degrowth’ are mathematically and socially identical. They are the same thing.” To show this, he uses the example of the economic decline following a time of rapid growth immediately after the Second World War—which involved “high productivity, high wages, full employment, expanding social benefits…”. In contrast, he argues that after the 1970s, according to “whichever metrics we use”, there was a decline in prosperity for all Americans.

Phillips denies degrowthers the ability to realize the most basic fact: more good = good, more bad = bad. And if growth is simply Everything That Is Good In The World, it becomes a hard thing to argue against: we’ve reached a conversational impasse.

The implication is that economic growth is directly related to material and social well-being, and “degrowing” would limit that kind of progress. Actually, during this time, well-being decreased just as consumption and economic growth sky-rocketed—a fact which he conveniently doesn’t mention. To avoid this fact, he usefully switches from defining economic growth as increase in productivity and material use, to defining economic growth as decrease in inequality. But different kinds of things can grow or degrow at different rates—a decrease in consumption is not the same as a decrease in well-being. In fact, since the 1970s, the US has only increased its per capita material use, not decreased it. Austerity does not inherently lead to a decrease in total consumption, nor does a decrease in well-being inherently require a decrease in material consumption.

His argument reminds me of a recent New York Times article about degrowth. As fellow degrowth scholar Francois Schneider pointed out in an email, in this article, degrowth was defined simply as a reduction of income. Not only does this misinterpret what, exactly, needs to degrow (hint: not well-being), it also feeds into the tendency—symptomatic of the neoliberal era—to reduce all kinds of well-being to monetary indicators.

Phillips continuously makes the same error: conflating income with wealth, material production with material well-being. While this is standard practice in development circles—used to justify land-grabbing, exploitative industry, and privatizations—you would expect different discursive tactics from a staunch anti-capitalist austerity-basher. Part of the degrowth framework has been specifically to argue that well-being and income have been conflated for far too long, with very negative consequences (such as the wholesale destruction of indigenous livelihoods for the sake of development).

Finally, when trying to counter the degrowth position, you’re also going to have to deal with the now well-known catchphrase that “infinite growth is impossible on a finite planet”. To do this, Phillips calls upon a pretty quirky theoretical model:

Think of a single rubber ball. Like the Earth, it is bounded in the sense that very clearly there is an edge to the ball and there is only so much of it. It doesn’t go on forever. It is not boundless. And there is only one of them. But it is infinitely divisible in the sense that you can cut it in half, then cut that half in half again, then cut that quarter in half, then that eight in half, and so on. In principle, with this imaginary ball, you can keep cutting it up for as long as you like, infinitely extracting from this finite object.

Phillips counters the necessity to degrow with a variation of Zeno’s paradox, hoping to show that, theoretically, infinite growth is possible on a finite planet, as long as it decreases at a negative exponential rate. Basically, in a finite world, you can keep on growing infinitely as long as you grow less and less, all the way to infinity. But this also involves acknowledging that positive exponential growth (e.g. a 3-5% growth rate) is physically impossible. Funnily enough, in trying to prove the possibility of infinite growth on a finite planet, he trapped himself in an argument that looks very similar to that of the degrowthers.

Phillips argues that, since it’s possible to conceive of a socialist system where economic growth leads to a low-carbon economy, economic growth is inherently a Good Thing. It’s reminiscent of another classic sophist argument: since it’s possible to conceive of God, He therefore must exist.

Similarly, later in the book, he concedes that we do need to move toward a low-carbon economy and that, within capitalism, this is impossible. But, rather than conceding that economic growth within capitalism is undesirable, he argues that, since it’s possible to conceive of a socialist system where economic growth leads to a low-carbon economy, economic growth (largely defined in capitalist terms, even as he rejects GDP elsewhere) is inherently a Good Thing. It’s reminiscent of another classic sophist argument: since it’s possible to conceive of God, He therefore must exist.

So what needs to degrow?

Let’s be clear, even if defenders of economic growth rarely are. Historically, economic growth (defined as total increase in measured economic transactions, or GDP) has risen along with social metabolism: the total consumption of materials and energy of an economy. Increased material-energy throughput is what makes climate change and environmental destruction happen, and engenders environmental conflicts around the world. Therefore we have to downscale our total material-energy throughput to address environmental and social injustice. Most available evidence points to the fact that decreasing total economic activity is the best way to do this, while still being able to provide adequate social safety nets.

Critics of degrowth spend most of their time trying to convince readers that decoupling economic growth from “the Bad Things” is theoretically possible, even as they rarely define what they mean by economic growth.

Degrowth, then, is about challenging the idea that infinite and positive exponential growth in monetary transactions (GDP) is the main tool for achieving well-being, today and for future generations. Further, degrowth is about acknowledging that exponential GDP growth has been, and will likely be for the foreseeable future, linked with rising material and energy throughput, and that this increase in total consumption has disastrous effects on the earth and its people. This comes along with a critique of GDP: many argue that it is a terrible indicator for well-being in the first place. It also comes along with criticizing the neoliberal demand to increase economic growth at all costs, even if this means subjugating an entire population to decades of debt (more on this in another piece).

There are many definitions of degrowth out there, but a commonly cited one is “an equitable downscaling of production and consumption that increases human well-being and enhances ecological conditions”. Under most definitions, degrowth is about maximizing well-being while minimizing energy and resource consumption (particularly in the rich nations) which may be mutually beneficial, and can address climate change to boot.

So degrowth is not about decreasing the Good Things. Nor is its main thrust that decrease in total consumption is the only thing that must be done. And all degrowthers I know would happily concede Phillips’ point that a change in the mode of production—involving a critique of capitalism, better use of technology, and better democratic planning—is necessary to avoid environmental and social Bad Things.

But they would disagree that the prerequisite for more Good Things is increasing total economic activity. In fact, the ideology of economic growth actually waylaid struggles for better welfare, helping to shut down the political action necessary to provide more Good Things.

Now, it is theoretically possible to decouple exponential economic growth (be it positive or negative) from exponentially increasing metabolic rates, even if no such thing has, as far as is known, been successfully implemented. Arguments for decoupling, including those in Phillips’ book, fail to take into account the embedded material and energy consumption of economies that have, so far, ‘dematerialized’ while GDP has gone up.

Krugman’s proposal for how to decouple remains in the neoclassical camp: toggling consumer preferences—demand, and regulating undesirable economic activity—supply, while continuing to increase economic activity on the whole. Farber and Phillips’ approaches are in the Marxist camp: radically shift the mode of production to rationally plan an economy, limiting the Bads and upping the Goods, while (presumably) continuing to increase economic activity on the whole.

To make their case, these authors have conjured up magical scenarios involving a slow ship economy and a post-capitalist socialist world order. Neither economies exist today. To really support their points, they would need to point to extensive research and probably some robust models, rather than possible worlds.

Take the case of Austerity Ecology: Phillips argues that socialist economic growth has the potential to save us, even as he does not draw on any examples of situations where this has occurred. It’s a cheap argumentative trick to defend economic growth today just on the basis that it could theoretically work under socialism.

So if they really wanted to defend economic growth as it exists today, this would be where the conversation would need to go: determining whether, and how, economic growth could keep going without exponentially increasing material and energy use. Bonus points: showing exactly why economic growth—defined as the exponential increase in monetary transactions at 3-5% per year—is desirable in itself.

But it is exactly at these points that the defenders of growth remain obscure. Rarely do they explicitly concede that, in fact, current rates of economic growth have been historically tied to increasing environmental degradation. Rather, they spend most of their time trying to convince readers that decoupling economic growth from “the Bad Things” is theoretically possible, even as they don’t define what they mean by economic growth.

And yet this approach actually suggests that they are already on the defensive: they are trying to save economic growth from the accusation that it inevitably leads to more “bad stuff”. Without proper evidence, and by shifting the definition of growth constantly to suit the needs of their arguments, the positions of growth-defenders start looking more like denial than reasoned debate.

In contrast, degrowth starts from the reality of the current economy. In this economic system, decoupling is very difficult, if not impossible. Therefore, because climate change is now and a global socialist economic order is not yet in sight, a realistic short-term strategy is to limit exponential growth in metabolic rates, most easily achieved by limiting exponential economic growth. This should be paired by a long-term shift to a more equitable, democratic economic system. Then, theoretically, a new economic system could be constructed where equitable economic growth does not lead to more fossil fuel consumption.

Whether we should focus on creating a global socialist system instead of shifting to a low-impact economy is debatable, but perhaps, just to be on the safe side, we could give both a try.

Thanks to Sam Bliss, Ky Brooks, Adrian Turcato, and Giorgos Kallis for their comments and feedback.

Aaron Vansintjan studies ecological economics, food politics, and urban development. He is an editor at Uneven Earth and enjoys journalism, wild fermentations, decolonization, degrowth, and long bicycle rides.