The Five Star Movement in Italy has been campaigning on a platform of direct democracy and environmentalism. This March, they won the largest percent of the vote and the most seats in Parliament. Sounds good, right?

Except that Beppe Grillo and Luigi Di Maio – the two foremost leaders of the party – have called for expelling all migrants from Italy and ending the flow of migrants to Europe. They entered into a coalition with the Lega Nord following the 2018 election, a party advocating full regional autonomy – and protecting the ‘Christian identity’ of Italy.

Direct democracy

Even as anti-authoritarian, anti-racist movements all over the world are working to take power where they live, self-described localist movements have also won elections with racist, and frankly fascist, platforms. New right movements like the Lega Nord have even adopted the more typically leftist, anti-authoritarian language of ‘autonomy’ and ‘direct democracy’.

Continuing our discussion of the potential pitfalls of radical municipalism, we want to address this toxic strain of localism – what we’ve termed dark municipalism – and why it is so dangerous.

If a diverse, egalitarian, and ecological local politics is to be successful, it must develop strategies for addressing and combating these tendencies.

Racism and Localism

The Nazis showed the world that it’s entirely possible to be both a back-to-the-lander and a genocidal racist. American militia movements have long fused struggle for local autonomy against the federal government with anti-immigrant hatred and white nationalism.

In the Pacific Northwest, fascist groups like the Northwest Front and the Wolves of Vinland have attempted to co-opt the vision of an independent Cascadia for the ends of white racial separatism.

Britta Lokting argues in The Baffler that there is a greater commonality between this white nationalist fringe and the other tendencies within Cascadian bioregionalism than we’d like to admit. “Ecologists, liberal hipsters, and the alt-right in the Pacific Northwest [all] resist some sort of outside taint.”

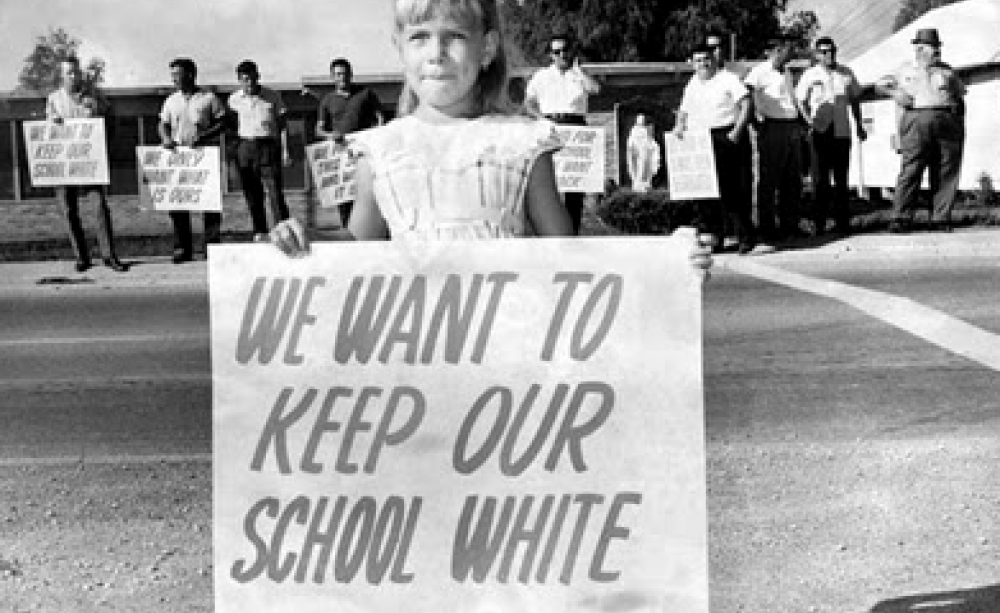

Movements for local control can easily slip towards racist and fascist politics by positioning a given community in opposition to outside threats. Oftentimes, savvy segregationists use the language of local control to mask the racial and class motivations behind their political projects.

Several European political parties like the Lega Nord have even begun to distort the term “direct democracy” to argue for “the people” (selectively defined) controlling national immigration policy as a means of achieving the authoritarian ethnonationalist system they envision.

Not all examples of reactionary localism are as extreme as Nazis and anti-government militias, however. It is also, for many people, very close to home, being central to the history of most American suburbs.

Suburban local control

When we think of racial segregation in the US, Jim Crow laws quickly come to mind. But localism—much of it in Northern cities—also played a big role in dividing US society along racial lines.

When urban rebellions rocked cities across the United States in the late sixties, millions of whites flocked to segregated suburbs. By forming new municipalities, sometimes across county lines, wealthy and middle-class whites were free to organise local policy around excluding people of color and the poor, while starving American cities of the tax revenue needed to sustain public services.

Suburban communities walled themselves off with more than gates. Local control over housing policy let them block the construction of affordable housing, to keep low-income people from ever moving in next door. By designing suburbs around cars rather than public transit, they ensured that no one without a car could even reach their communities.

Suburbanisation was both a social and ecological catastrophe. All across the US, urban areas were flattened outward into low-density, energy-intensive sprawl, swallowing up ecosystems and farmland. (To give a sense of how disastrous this has been for the climate: the average carbon footprint of suburban households is four times larger than the average household’s in dense cities.) Job centers were displaced and made harder to reach by transit, leaving many inner cities in a crisis of chronic unemployment.

Most importantly for this discussion, suburbanisation fortified racial segregation in the very political structure of many metro areas, with wealthy, mostly white suburbs governing themselves independently from and at the expense of communities of color.

This brought the gains of the civil rights movement to a halt, with incalculable human costs. Local political autonomy, as this example illustrates, can easily become a vehicle for segregation and defunding the public sphere, and has genuinely destructive potential.

Public education is another important terrain of reactionary localism.

Generally speaking, local funding for public schools has resulted in deeply unequal educational outcomes for non-white and poor children (which is why many states have taken over school funding from local property taxes, to be allocated more equitably).

Many school districts around the United States have taken educational inequality a step further, with segments breaking off to form wealthier, whiter districts, depriving less privileged children of essential public resources. Seventy-one communities have attempted to secede from their school districts since 2000, and forty-seven of them have succeeded. To quote one community member of a Chattanooga suburb advocating for this sort of entrenchment of school segregation: “Local control is power.”

From anti-immigrant movements to segregated schools, we’d do well to take these hard lessons to heart when rebuilding our society from the local level.

The language of “local control” is central to the political strategy of segregation and resegregation. It allows officials and advocates to apply a palatable, race-neutral framing to fundamentally racist policy. Power consolidated fully at the local level is potentially pernicious precisely because there is such deep inequality between local areas in our highly segregated society.

Local government is a terrain the right wing knows very well, and if empowered carelessly, one that can directly further reactionary agendas. The problem is deeper than an unfortunate correlation between localist movements and racism. Because suburban municipalities had political autonomy, they were able to realise and institutionalise this segregationist agenda.

So how should we deal with this?

We have some ideas: actively undoing bigotry through organising itself, building connections beyond the local into our political project, and developing a grassroots political system around the principles of democracy and interdependence over autonomy and local control.

Building Power, Bridging Divides

Building grassroots, democratic alliances to take back control over the places where we live is easier said than done. Organising with your neighbours can be rewarding, but also tiresome and depressing. In the little spare time each of us has, it often feels easier to talk to people we already know who share our own values.

The truth is that community organising is hard work. Organisers are confronted every day with resistance to their ideas, not only from political opponents but from other community members who have become resigned to the oppressive status quo as well.

Movement-building takes time, through years of real human connection. The simple fact is that there are no shortcuts to moving beyond bigotry either.

Community organising has traditionally aimed to overcome social divides—racial, sexual, cultural—through human relationships. Organising relies on building relationships to recognise common interests. These common interests let people identify the things they can organise around for their common good, and their relationships supply the power to actually win. Through recognising commonalities and taking collective action, bonds between people across difference are forged across differences, uprooting prejudices and fears.

Radical democracy is a framework for extending that process across all areas of life.

As we carve out space for participatory, collective decision-making, either in the workplace through cooperatives or where we live through neighborhood councils and tenant unions, we cultivate a more expansive understanding of shared interests across racial and sexual hierarchies, and of how those inequalities pose barriers to our own democratic struggle.

We can build a new commons together that meets the needs of everyone through this deep organising, a community interdependence held together by strong relationships.

Class conflict

But is stopping fascism as simple as making friends with your neighbours? We can’t lose sight of the fact that there are real, material, conflicts between people.

Friendship between a tenant and their landlord can’t erase the exploitative relationship between them. Only by pursuing an intersectional class politics can we piece apart the forces that divide us.

Hateful and discriminatory attitudes don’t operate in a vacuum. They have a history we can trace and material roots we can transform. Capitalists have spent centuries cultivating racist and nativist narratives to keep exploited people scapegoating each other.

The labour movement in the United States has historically hampered itself through its own racism. By refusing to fraternise with black, Latino, and Asian workers, white workers have undercut their potential power. We can’t afford to make these mistakes.

Visionary organisers need to make the case again and again, through their actions, words, and the resources they build, that ordinary people can only realize their deeper interests of freedom, a healthy life and planet, and real democracy by lifting up people at the margins.

Steps to expand participation—from translation to accessibility for disabled people to prioritizing childcare at meetings—can only make our movements more powerful. A socially transformative politics teaches more privileged people that their common cause lies with the oppressed, through democracy in everyday life.

Beyond building real relationships and making our movements more accessible, we need to make sure that we can create resources for everyone. Tenants rights action groups, community kitchens, and self-organized disaster response groups are all ways of offering people the things they need, all the while building alliances across race and class and addressing loneliness. Social isolation feeds a steady supply of alienated people to the far-right.

As we build a community economy beyond capitalism, we strike at the roots of all these things.

Beyond the Local

As we argued in our last column, radical municipalists must work to build power beyond the local in order to overcome capitalism and the state.

We have no hope of winning real power for our community without this wider network of popular struggle across municipal and national borders. This is also an important part of overcoming prejudices and inequalities between different communities.

Confederations of community councils and assemblies bring us into common cause with those we might otherwise consider outsiders. Even if your own neighborhood isn’t very diverse, scaling up the practice of radical democracy can have the same transformative impacts we discussed above on a much wider level.

Municipalism that is confederal is an antidote to xenophobic isolationism. It’s a localism which knows no national borders, yet retains the ability of citizens of every community to have a say in the affairs which affect them. The power of our strategy itself relies on building bridges rather than walls.

Building a New System

Lastly, as we develop new institutions of solidarity and democracy, we need to go beyond mere autonomy as an organisational principle. Autonomy is about securing freedom from an oppressive outside, but we’re not just trying to resist the system. We’re working to build a new system, a new society.

Anarchists and other anti-authoritarian leftists have long stressed the importance of autonomy. Bodily autonomy is a fundamental moral principle for a free, feminist society. Liberation struggles of all types have articulated their just vision in terms of autonomy.

Building autonomy for individuals and communities is clearly an essential aspect of resistance and dual power, but it is limiting as a framework for the reconstruction of a better world.

Autonomy is in essence a negative political value, being defined in terms of freedom from. It conveys nothing about the actual governance of an autonomous community, and defines its relations to other communities in exclusively negative terms. It amounts to non-interference by outsiders or outside sources of repression.

Given all the potential dangers of local political autonomy, we need to be intentional about the kind of democracy we are building from the ground up. This means thinking through how a future system would equitably solve specific problems beyond the local level.

In our previous columns, we’ve made the case for a system of directly democratic assemblies organised into confederations, which would come together through recallable delegates to coordinate activities regionally and beyond.

To prevent the rise of dark municipalism, however, confederations will have to be stronger than voluntary associations of autonomous communities.

We live in an unequal society, which we are trying to change by expanding the sphere of democracy. We undercut that goal if our conception of a truly democratic society is one where the wealthiest can wall themselves off without accountability to the wider human community.

Differing interests between particular neighborhoods, cities, and countries are inevitable on bigger questions—regional transit, watershed management, total decarbonisation of the economy, redistribution of wealth. None of these can be resolved through a confederation of fully autonomous communes where unanimous agreement is required for them to act together. We can theoretically educate away prejudice, but we can’t educate away conflicting economic interests. A deeper political relationship is necessary.

‘Confederation’ should be conceived as layers of democracy, from the neighborhood to the worldwide. The defining principle of a confederal system is not community autonomy, but interdependence. This is a much stronger basis for the protection of human rights and radical democracy.

Interdependence is what makes municipalism and democratic confederalism unique among locally oriented political ideas: they are not intended to be withdrawals from global affairs and obligations, but movements for radically restructuring the balance of power in how decisions are made towards ordinary people, be that locally, regionally, or globally.

Democracy All the Way Down

Many progressives see these forms of reactionary localism and conclude that we need a strong centralized government to better protect marginalised people. In particular, we as radical municipalists have to take seriously the history of federal power in securing greater freedoms for black people in America.

After the American Civil War, Reconstruction continued only as long as federal troops occupied the South. Desegregation and voting rights for African Americans were achieved through federal court cases and legislation. The very principle of “states’ rights” which helped uphold American apartheid and slavery is itself a form of more local autonomy.

But governments only gave in when forced by the power of popular movements. When the state is removed from the people it governs, through unaccountable bureaucracies, technocracies, or oligarchies, it gets a free pass for abuse, oppression, and exploitation. For instance, while suburbanisation in the United States was driven by racism, it was also a product of social engineering by federal policy, through redlining, freeway construction, and incentivizing industries to relocate from cities to suburbs. Many of the Trump administration’s ongoing crimes are only possible because the people do not exercise direct control over their government.

We can’t maintain an oligarchy in the hopes that the ruling class will force through needed changes with respect to racial and economic equality.

The consolidation of authority into a small ruling class necessarily tends toward more oppression. To keep this system of hierarchy in place, the powerful always seek to divide and control the less privileged.

Ordinary people are far from perfect. But it’s ordinary people, with all their differences and shortcomings, with whom we build a more perfect world.

It’s only through lived experience that any of us can learn that we share common ground with others. When we, as organisers, go to where people are, offer the resources they need, build bridges across racial and class differences, and make decisions together, we slowly build the foundations of a new society.

At the end of the day, it’s only democracy—all the way down—that can give us any hope of universal emancipation.

This article was originally published in The Ecologist.

The Symbiosis Research Collective is a network of organizers and activist-researchers across North America, assembling a confederation of community organizations that can build a democratic and ecological society from the ground up. We are fighting for a better world by creating institutions of participatory democracy and the solidarity economy through community organizing, neighborhood by neighborhood, city by city. Twitter: @SymbiosisRev. This article was written by Mason Herson-Hord (@mason_h2), Christian Bjornson (@VoxLibertate), Forrest Watkins (@360bybike), and Aaron Vansintjan (@a_vansi).