by Kendall Dix

Countries of the Global South are facing a modern form of economic domination from foreign interests. The story of Europeans plundering Black and brown nations to profit from their natural resources is probably a familiar one. But now that nature itself has become commodified through the tourist economy, environmentalism functions as a justification for replicating the same old colonial power dynamics.

Under the banner of conservation, green nonprofits in the United States have begun using the government debt of previously colonized nations as a bargaining chip to force governments to create new nature preserves. Just over two years ago, the U.S.’s richest environmental organization, The Nature Conservancy, partnered with big European banks to coerce Seychelles, a small island nation 1,000 miles east of Kenya in the Indian Ocean, to issue “blue bonds.” These bonds are a new debt instrument that are supposed to be good for the environment and attract investors who believe Wall Street can be a driver of public good.

Blue bonds are modelled on “green bonds,” another market-based climate solution that can enable companies to claim they are engaging in environmentally friendly solutions while actually achieving little positive environmental benefit.

On October 29, 2018, the World Bank and The Nature Conservancy announced that the government of Seychelles would issue $15 million of blue bonds, “a pioneering financial instrument designed to support sustainable marine and fisheries projects.” Blue bonds function just like regular bonds. If a government or company wants to borrow money, it issues bonds that are sold in bond markets. The government gets a lump payment upfront and then pays the money with interest over time to the holders of the bonds, which can then be bought and sold on markets just like stocks are. Bonds are considered safe investments because governments rarely default on their debts. What makes blue bonds “blue” is that the issuer of the bond is supposed to use the money on ocean conservation. In the case of Seychelles, the nation issued the bonds to pay off some of its national debt and turn 30 percent of its coral reefs into marine protected areas (MPAs).

The Nature Conservancy says blue bonds are “an audacious plan to save the world’s oceans” and “could unlock $1.6 billion for ocean conservation.” Blue bonds are modelled on “green bonds,” another market-based climate solution that can enable companies to claim they are engaging in environmentally friendly solutions while actually achieving little positive environmental benefit. For example, a Spanish oil and gas company sold green bonds to finance upgrades to their oil refineries, a project of dubious environmental benefit given that it facilitates continued greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the project was sold to investors as a “green” project because it promised to marginally reduce emissions within Spain’s existing oil industry.

While the bulk of media coverage about the blue bonds deal heralded it as a win-win for conservation and Seychelles, nobody seemed to notice that a U.S. nonprofit used a sovereign nation’s foreign debt to leverage the closing of a huge portion of its fishing grounds. We should call the move to deliver conditional aid to Seychelles premised upon reordering its economy what it is: “neocolonialism.” Neocolonialism is the extension of colonial practices through the exertion of economic, political, or cultural pressures to control or influence previously colonized nations.

No fishing

Fisherfolk tend to have mixed views on MPAs, and many are outright opposed. They argue that MPAs are overly restrictive and economically punish fisherfolk while showing limited conservation benefits. Fisherfolk argue that commercial fishing can be sustainable, and some would prefer limiting their days on the water or restricting certain types of destructive fishing practices.

In the United States, conservation initiatives have targeted small-boat seafood harvesters for decades now. Many of these small-scale harvesters are Indigenous peoples who have fished sustainably for centuries. For instance, in the 1960s, the Nisqually, Puyallup, and Muckleshoot nations had to fight the state of Washington for the right to catch salmon. Washington State’s salmon stocks had been declining since commercial fishing took off after World War II. Tribal communities had been partially blamed for the decline and were beaten and arrested by police for fishing that was guaranteed to them by treaties signed by the state. In the 1980s, environmental activist groups Greenpeace and Seashepherd targeted Indigenous tribes in Alaska and the Soviet Union for the legal harvesting of whales. When environmental groups are looking for easy victories to publicize, nonwhite people and developing nations such as Seychelles, with limited political power, seem to make for easy targets.

For Seychelles, where more than one in six people is employed in the fisheries sector, the potential hamstringing of the country’s second-most important industry could have lasting impacts on the autonomy of small-scale fisheries to determine their livelihoods and futures. It may be that Seychellian fisherfolk and the general public do prefer the creation of MPAs to limit commercial fishing, but there is nothing in the public record to indicate that they were even asked. If the people of Seychelles wanted to create MPAs, the nation already had democratic institutions to work through. Conditioning needed aid on the creation of nature preserves deprives them of their national sovereignty.

Up to its neck in debt

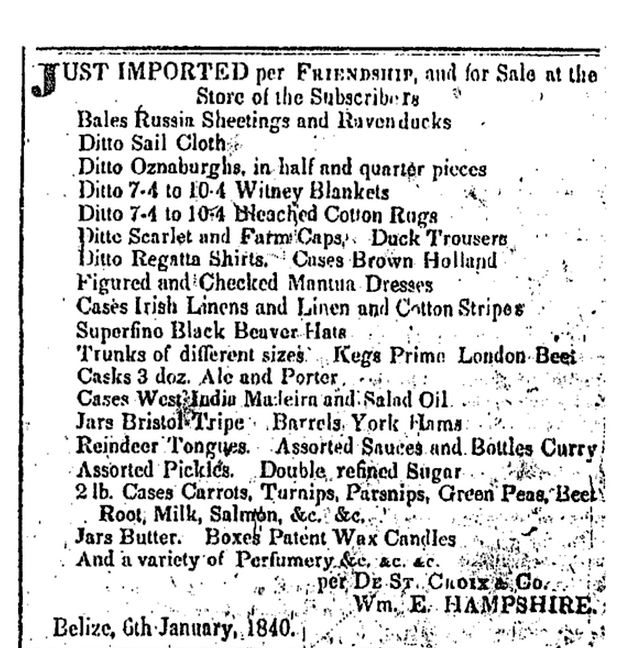

In 2008, Seychelles defaulted on its national debt to foreign banks. The nation owed significant amounts of money to banks in the European Union, largely to its former colonizers France and Britain. Seychelles’ debt had reached unsustainable levels due to two major factors. Firstly, the island nation has been on the losing end of uneven foreign trade in which it imports expensive goods such as oil and yachts while exporting relatively inexpensive natural resources such as tuna for canning. Secondly, Seychelles has been limited in its ability to generate revenue because of overly generous tax breaks offered to foreign investors during its transition to a tourism-based economy and a tax haven. When nations cannot generate revenue through taxation or exports but still must import expensive goods to finance economic development, their governments have little choice but to borrow money from foreign banks.

When the global economy collapsed in 2008, tourism to the Seychelles slowed down. At the same time, oil prices shot through the roof and further crippled a Seychellian economy reliant on oil imports.

From the EU’s economic perspective, Seychelles’ problems have resulted not from extractive global capitalism and coercive debt relationships but from overly generous domestic programs that support the second-longest living population in sub-Saharan Africa. This sentiment is illustrated by a statement from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that socialism had “eroded the work ethic” of the Seychelles, a statement that is shocking in its obfuscation of uneven debt relations, its McCarthyite redbaiting, and its placement of value on economic growth above the wellbeing of the people of Seychelles.

In 2010, France forgave about five percent of Seychelles’ total debt, but the IMF had other plans for the remainder. In a move straight out of a playbook from Naomi Klein’s “Shock Doctrine,” the IMF demanded that Seychelles further liberalize its economy and decrease welfare spending in exchange for restructuring its debt payments through 2017. Liberalization typically involves reducing trade barriers, rolling back financial and environmental regulations, slashing public benefits, and privatizing public resources. European countries and the United States have often strong armed developing nations to liberalize their economies in order to enable multi-national corporations to extract value from a nation’s natural resources.

As the debt restructuring deal expired, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) emerged from the nonprofit sector to leverage the debt to limit Seychelles’s fishing industry. TNC’s CEO at the time was Mark Tercek, a former managing director and partner at investment bank Goldman Sachs. Tercek wrote a book called “Nature’s Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature,” detailing how big business could profit off of environmental conservation. Blue bonds are one instance of the realization of Tercek’s vision of banks and environmental groups profiting off conservation.

The Nature Conservancy: A nonprofit with more money than some nations

TNC was founded in the United States in 1951 and is one of the largest environmental nonprofits in the world. TNC’s mission is to protect nature from human activity, an idea grounded in the belief that humans and nature cannot coexist. Its preferred tool for conservation is easements, which are restrictions on development that can attach to property through private sales contracts. These easements can provide big tax breaks for TNC’s wealthy donors and partners, which include oil companies, Dow chemical, and the charity arm of pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and Co. TNC has a presence in 79 countries and an endowment of $6 billion. In contrast, The entire GDP of the Seychelles is less than $1.7 billion. TNC is funded by grants from large foundations and membership dues, but it also generates revenue through investment income and land gifts.

In 2001, TNC expanded its focus to include “debt for nature” swaps, where it used a similar scheme in Southeast Asian and Central American forests as in the Seychelles to buy the debt of struggling nations in exchange for the creation of more nature preserves. In the Seychelles deal, TNC worked directly with the World Bank (the IMF’s sister organization) to buy some of the country’s debt in exchange for the creation of 13 new MPAs. TNC gets to claim credit for protecting coral reefs from fisherfolk, but it’s also receiving 3% interest payments on the debt from the Seychellian government.

The World Bank says it is backing the blue bonds because a healthier ocean will create a healthier economy. The stated commitment to a healthier ocean is admirable, but the World Bank’s implementation of the goal involves tactics that are paternalistic, coercive, and primarily benefit large corporations. Further, the economic value of MPAs is difficult to quantify. Some studies have found that MPAs don’t deliver environmental benefits, particularly when compared to conventional tools used for fishery management such as catch limits or gear restrictions.

So, if the environmental and economic benefits are dubious, then one has to wonder whether this deal is really supposed to benefit the Seychellian people. The Nature Conservancy and the big European banks holding their debt could simply have forgiven the Seychelles’ debt, but in the words of colonist Winston Churchill, that would have let a good crisis go to waste. With less debt pressure on its economy, Seychelles would have been more free to use its natural and financial resources how it sees fit.

As the largest environmental nonprofit in the United States, TNC controls large swaths of land and brings in revenue at levels comparable to small nations, in part thanks to interest payments by Seychelles and other nations in the Global South. TNC’s money and its influence give it considerably greater options than other environmental nonprofits to influence the direction of environmental protection. When TNC embraces “market-based solutions,” politicians and other environmental groups begin to see those tactics as appropriate and effective. In other words, TNC’s considerable political and economic clout increases the perceived legitimacy of market-based solutions and directs others to jump onto the bandwagon.

Again, the effectiveness of MPAs as environmentally beneficial is disputed. But even if MPAs offer the best protection from harms caused by fishing, MPAs still do nothing to protect marine areas from climate change or other environmental stressors on fisheries. MPAs don’t prevent damage to coral reefs caused by pollution that originates on land. Seychelles lost 90 percent of its coral reefs in 1998 not to overfishing but to coral bleaching, which is exacerbated by warming waters and climate change.

If MPAs don’t protect against climate change or development threats and may not even enhance fishery production, then blue bonds start to look a lot like coercive conservation designed to benefit wealthy outsiders. We also know that real estate development damages coral reefs, so it’s safe to assume that the hotels built during the tourism boom also played a role in the destruction of coral reefs that helped create the justification for issuing blue bonds. Ironically, one of the economic selling points of blue bonds is that protecting the reefs will keep the tourist economy afloat, which could create the demand for more hotels that would further damage the reefs. This creates a feedback loop where conservation may actually put more pressure on the environment, as documented in places such as Machu Picchu in Peru and in several U.S. national parks.

A history of extraction

The World Bank’s description of blue bonds as “pioneering” is telling. The word “pioneer” evokes a history of European colonial expansion, resource extraction, and domination of darker skinned people. For several centuries, Seychelles functioned as a European outpost that used the archipelago’s natural resources to benefit Europeans. It was supposedly uninhabited until it was colonized by the French in the 1700s. As first a French and later a British colony, Seychelles was primarily a source of spices, coconuts, and other agricultural products that were produced on plantations with slave labor. Today, most of its people are creole, or of mixed European and African descent.

The original colonization of Seychelles occurred during the heyday of triangular trade, which was an early economic model of globalization in the 17th and 18th centuries. European and North American slavers extracted people from Africa for the slave market and sent them to the colonies in the so-called New World. The colonists used this forced labor to process the vast natural resources of North America and send value-added products back to Europe where they would command a higher price. European slavers could then trade these manufactured products in Africa for more slaves. The entire system was financed by European banks. It was in this context that Seychelles was colonized. The same model of resource-based extraction and plunder of Africa continues to this day through coercive conservation.

In 1971, Seychelles was still under direct colonial control. The British constructed an international airport and tourism quickly replaced agriculture and fishing as the number one industry. Hotels sprouted all over the archipelago and soon dominated the local economy. In 1976, a socialist-led independence movement gained popular support, and (with the blessing of the United States government which was building a military base on one of the islands at the time), Seychelles finally broke free politically from the United Kingdom.

The economy, though, continued to depend on support from foreign tourists and investment. By 2019, services such as tourism and banking accounted for more than 72 percent of Seychelles’ GDP. However, very little of the money stayed in Seychelles. From the beginning of the boom, profits from the tourism sector were captured by foreign hotel companies and booking agencies.

The future of conservation?

The blue bonds model may not be limited to the Seychelles for long. TNC continues to tout the benefits of blue bonds and marine reserves, but blue bonds could also play an increasing role in the climate and oceans policy of the next President of the United States. Heather Zichal, who was the vice president of corporate affairs for The Nature Conservancy when the blue bonds were first issued, advised the Biden campaign on environmental policy. She was also briefly the executive director of Blue Prosperity Coalition, an organization dedicated to limiting fishing to 30 percent of the oceans.

The Nature Conservancy’s unholy alliance with fossil fuel companies and big banks represents everything that’s wrong with modern environmentalism.

Previously, Zichal said that she wanted to create an environmental policy that finds “middle ground” with oil and gas companies. It would seem incompatible for someone working on behalf of the ocean to find common cause with the businesses responsible for causing ocean acidification through the release of carbon emissions while actively preventing any meaningful climate action. However, Zichal also has financial connections to the oil and gas industry. She was paid more than $180,000 a year to serve on the board of Cheniere Energy, a natural gas company. She was appointed to Cheniere’s board shortly after leaving the Obama Administration where she served as Deputy Assistant to the President for Energy and Climate Change. Zichal had been identified as a top concern by progressive groups who don’t want Biden to involve her in the new administration.

Now that Biden is President, Zichal has been hired to head a new renewable energy lobbying firm that will seek to use her connections to the new administration to push for more support for wind and solar. Zichal’s career is a perfect example of the “revolving door” of politics, where high level government officials can leave administrative work for prominent positions in the corporate nonprofit/consulting world while also serving on the board of some of the world’s worst polluters.

The Nature Conservancy’s unholy alliance with fossil fuel companies and big banks represents everything that’s wrong with modern environmentalism. A corporate approach to environmentalism that perpetuates systems of domination is not just flawed; it is doomed to fail in the long term because it continues to empower the very forces that view “nature” as something that can be used up until it’s no longer profitable.

TNC is certainly not the only nonprofit that helps prop up a global economic system grounded in extraction, but it is one of the system’s largest nonprofit beneficiaries of money and land donations. And while a number of gifted scientists and advocates make up the rank and file of their 3,500 employees, the organization as a whole suffers from a lack of vision.

Unfortunately there are two major problems with TNC and a large portion of the environmental movement:

- Many people within it are unable or unwilling to recognize that unfettered extraction of environmental resources is intrinsic to capitalism.

- Many environmentalists still hold Malthusian notions that human beings are incapable of coexisting with nature.

TNC and similar groups’ missions to protect nature in its “wild” state is itself a problematic notion rooted in indigenous erasure. Prior to the rise of European colonization and triangular trade, hundreds of nations of people lived on the American continent. They lived, hunted, farmed, fished, and built things from the Arctic Circle to Patagonia.

When we set up a society that says some places are for people and some places are for “nature,” we reinforce the idea that it’s okay to trash the places that are for people. It also justifies the expulsion of the people from spaces set aside for “nature”, and the denial of relatedness and kinship between the two. Instead, we need to recognize that humans and our habitats are inherently a part of nature and rebuild our systems accordingly.

If the people at TNC and other environmental nonprofits are truly interested in living in harmony with nature, they would have to radically transform their own organizations to focus on disrupting an economic system that relies on exploiting natural resources. After all, it was the global imbalance of power and extractive model that originally generated Seychelles’ dependency on foreign tourists, foreign exports, and foreign fishing interests.

But until TNC and the World Bank reckon with capitalism itself, blue bonds will just help reinforce the unequal global order that makes Seychelles reliant on foreign aid and debt. Whether the bonds are blue or green, neocolonialism with an environmental justification is still just neocolonialism.

Kendall Dix works on climate policy and lives on a farm outside of Charlottesville, VA.