by Tim Crownshaw

Nothing happens without energy. Literally. Lacking energy, there can be no heat, food, motion, information, or life. Commonly defined as ‘the capacity to do work’, energy has always been central to human societies, whether derived mechanically from moving wind or water, chemically from wood, oil, coal or other combustible fuels, or thermally from the sun. This is more than an abstract footnote—there are deep links between available energy and the very structure of civilizations, including their types of social organization and levels of complexity, as noted by anthropologist Leslie White [1]. While this relationship is obviously not deterministic, there are social, technological, and economic arrangements, such those we enjoy in privileged parts of the global North today, which are likely unattainable at significantly lower levels of energy consumption.

Much discussion and research in recent years has focused on the prospects for a global transition to renewable energy, motivated by growing awareness of the existential threat posed by global climate change as well as localized environmental issues attributable to the production and consumption of fossil and nuclear energy. The Green New Deal (GND), the subject of this essay, is the latest in a long line of ambitious plans aimed at accelerating this process, in addition to its social and economic goals. However, many of these energy transition plans are conceived teleologically: they start with the outcomes they seek to achieve, then fill in the gaps with implied (but uncertain) socio-technological capabilities. In the process, they typically sidestep irreducible uncertainties and fail to properly engage with the considerable challenges involved in fundamentally transforming our energy system. It must be asked whether the GND commits these same errors. Avoiding them requires recognition that the transition to renewable energy is not simply the eventual outcome of the right set of policy settings, but what systems scientists would call a complex, path-dependent, socio-metabolic process. In other words, the transition will be far more constrained in terms of what we can achieve than we often like to think and will necessarily transform the basic configuration of our societies [2, 3].

Many of these energy transition plans are conceived teleologically: they start with the outcomes they seek to achieve, then fill in the gaps with implied (but uncertain) socio-technological capabilities.

That we must one day rely solely on renewable energy is true by definition. The fossil and nuclear fuels are depleting resources and their use entails ecological harm on an immense scale. Therefore, this use will eventually become infeasible, unacceptable, and uneconomic. But how we get from here to there is radically uncertain. There is no guarantee that we will complete the transition while maintaining an industrial socio-metabolic regime (our current pattern of material and energy use and associated societal configuration). In fact, this appears highly unlikely [2, 3].

Alternative narratives

For most people in the developed world, modern energy services are so ubiquitous and ingrained in our daily lives that they have been rendered largely invisible (at least until they are interrupted). Nevertheless, understanding energy is critical to accurately discerning where we are going as a society and what we can hope to achieve. This understanding suffers from what Mario Giampietro has called a “clash of reductionism against the complexity of energy transformations” [4].

Energy is typically understood in loose terms as something produced and transported by large and highly visible infrastructures (of which there are ‘good’ kinds and ‘bad’ kinds, defined by one’s perspective). It is generally perceived that energy is used for various crucial purposes, such as moving people and things around, heating and cooling homes and workplaces, powering appliances and devices, and producing consumer goods. Beyond this, various emotionally charged and frequently oversimplified narratives come into play, which inform expectations of what lifestyles and society at large ought to look like. While the range of perspectives and positions on energy is vast, they can be broadly grouped into two opposed narratives:

- Narrative one sees energy presenting an urgent moral duality: oil derricks, pipelines, smog-covered cityscapes, and corporate interests on one side and climate saving technologies, eco-friendly behaviours, and new political movements on the other. In this strain of thought, we already have the requisite technology to carry out the transition to renewable energy and the only serious barriers are political in nature. Nowhere is the first narrative more clearly depicted than in US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s recent ‘A Message From The Future’ video.

- Narrative two considers fossil fuels to be miraculous, prosperity-building, and geo-politically important resources, which should not be disregarded in favour of unproven, unreliable alternatives. As for climate change, positions can range from “the science in not settled” to “no problem, we’ll have the tech for that”. This narrative is captured in PR communications from major oil companies (and even more transparently depicted here), frequently loaded with promises of jobs, technological breakthroughs, and nostalgia for an era of pioneering industrial vitality.

Neither of these narratives is totally correct, but neither is totally wrong either. The first rightly highlights the social and ecological imperatives we face and how some forms of energy production are significantly less harmful than others, but tends to downplay the challenges and implications of transforming the entire energy basis of modern economies. Meanwhile, the second accurately identifies the unique qualities of fossil energy resources and their role in reaching our current level of development, but fails to identify that these have a limited lifespan, both in terms of their physical abundance and the extent to which we can use them without unacceptable consequences. It is on this fraught ideological landscape that the GND must vie for influence against competing visions of our energy future.

The Green New Deal

The GND (a clear allusion to Roosevelt’s depression-era New Deal) burst onto the US political scene in 2018, emerging from the youth-led ‘Sunrise Movement’ and subsequently championed by freshman congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and a growing list of progressive political figures. Its supporters now include Joseph Stiglitz, Ban Ki-Moon, Paul Krugman, US senators (Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, and Ed Markey), and numerous organizations (including Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, Sierra Club, 350.org, the New Economics Foundation, Extinction Rebellion, and the United Nations Environment Programme). The concept has quickly spread internationally to Canada, the UK, Australia, and the European Union due in large part to the advocacy of respective green parties in these places. A recent Yale survey found a strong majority in the US (81% of those surveyed and even 64% of republicans) ‘strongly support’ or ‘somewhat support’ the various proposals associated with the GND. With this impressive momentum, the time has come to translate zeal into workable policy.

In the US, the GND is often described with the tagline “decarbonization, jobs, and justice.” Policy proposals center around a green industrial revolution—a rapid, large-scale transition to renewable energy alongside vastly expanded public transportation and building retrofits for energy efficiency within a 10-year timeframe. The plan is to achieve near carbon-neutrality of the US economy and improved environmental quality through immense public spending initiatives, funded primarily via redistributive measures designed to tackle inequality. The draft text of the GND House Resolution includes the aim to “virtually eliminate poverty in the United States and to make prosperity, wealth and economic security available to everyone participating in the transformation.” Variations often include increased minimum wages, universal health care, improved access to education, shorter working hours, and democratized workplaces. For a more complete description of the origin story and details of the GND, see this article or this one.

As the GND ultimately hinges on energy transition, the feasibility of its assertions in this area are crucial.

Although it’s not hard to see the appeal, no one would deny that this is an immense task. In fact, there is already a chorus of critical voices from right across the political spectrum on questions of cost, timeframe, technical assumptions, and policy design. As the GND ultimately hinges on energy transition, the feasibility of its assertions in this area are crucial. To go any further, we need to cover some energy basics.

Energy primer

The global energy system is by far the largest, most technologically advanced collection of built capital, supporting infrastructure, expertise, and organizational capacity that has ever existed. Despite the hype around renewables, the global energy system is still 96% non-renewable, while solar and wind—the two renewable energy sources with the greatest growth potential—supplied just a little over 1% of total world energy in 2018 [5].

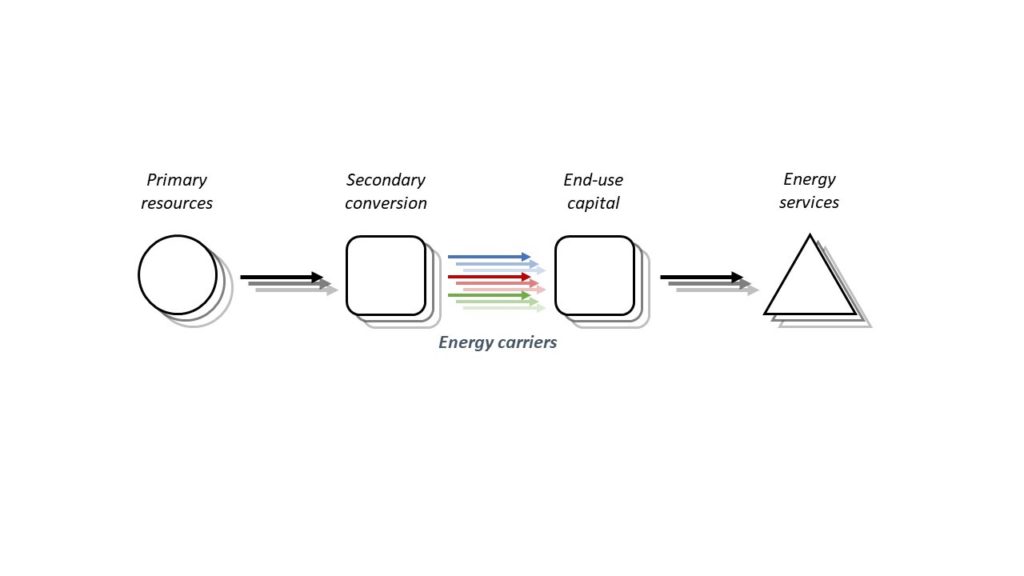

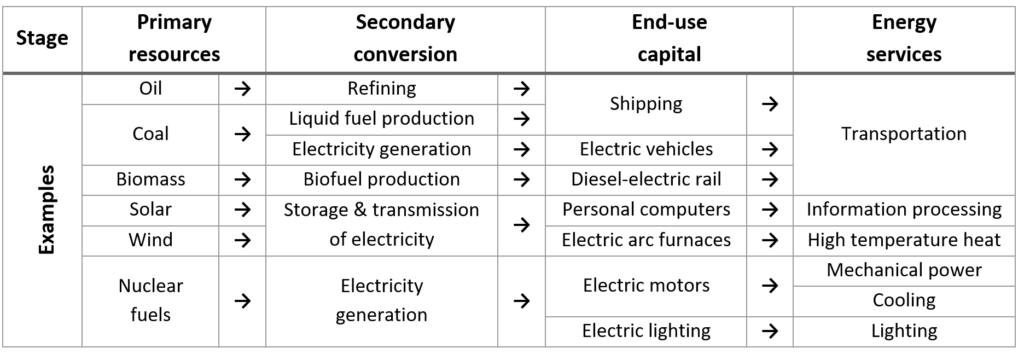

Firstly, it is important to understand that each type of energy production can satisfy only some types of energy demand: energy resources and the flows derived from them are not interchangeable. Instead, the energy system comprises a series of distinct flows spanning four basic stages, from primary resources through to delivered energy services:

To provide a bit more specificity to this picture, the table below shows common examples of each of the four stages and sequences of flows between them:

If fully enumerated, this would look more like a complex, multi-nodal network rather than a straight line, but this simplification serves to highlight some key features:

- Changes at one stage require corresponding changes at all other stages in order to avoid supply bottlenecks or unused excess capacity. Each new increment of supply (primary resources plus secondary conversion) must be met with a corresponding increment of demand (end-use capital plus energy service demand) and vice versa. This means that investments needed to change the system are often larger than they first appear—investments in one part of the system require corresponding investments in others—and the ways societies use energy must evolve as supply changes.

- The common lay concept of ‘energy’ as a homogeneous, aggregate quantity is a fiction. The various flows within the energy system are non-equivalent and non-substitutable (at least not directly). For example, gasoline is produced by a refinery and fuels your car, but this is not interchangeable with the electricity generated by a gas-fired turbine powering your laptop. In particular, the flows of ‘energy carriers’ between the second and third stages—consisting of electricity, liquid fuels, and heating fuels—must be considered separately, otherwise we risk overlooking constraints integral to the system.

The non-equivalence of energy carriers is an essential concept, analogous to the metabolism of living organisms requiring fats, proteins, and carbohydrates to survive. For most animals, diet can change with food availability, but there are limits to this. Humans can substitute one food group for another, at least for a period of time, but beyond certain boundaries severe physiological consequences begin to occur, including starvation and death. The energy system functions basically the same way. The composition of supply or demand can’t be changed arbitrarily and to the extent that it can be changed, this typically requires expensive and time-consuming adjustments at other stages in the energy system.

Energy for energy

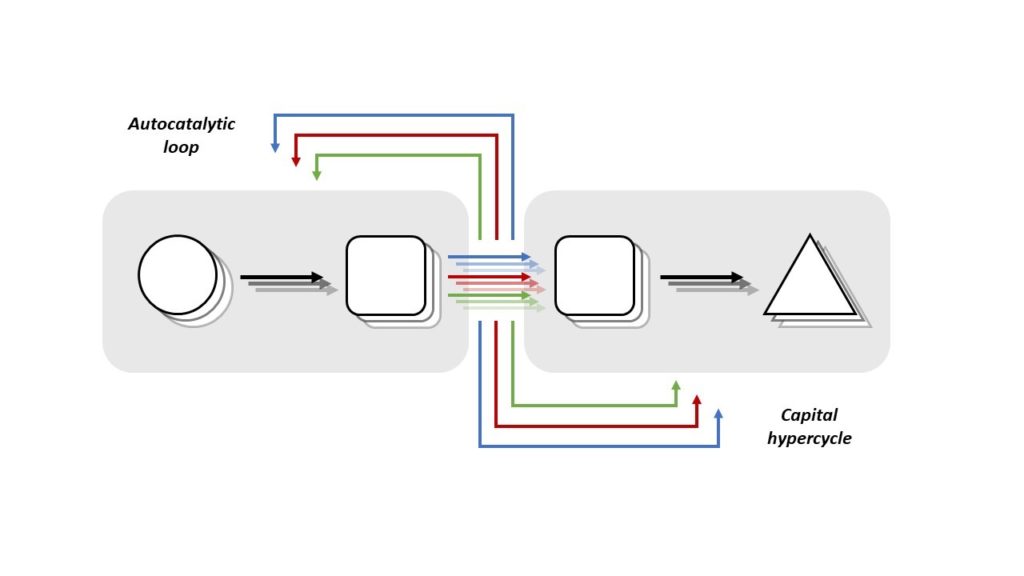

Aside from the flows ultimately ending up as final energy services (or waste), a large part of the output of the energy system must be directed back into its own construction, operation, and maintenance. These flows represent the metabolism of the global energy system. As shown in Figure 2, energy carriers are utilized in an ‘autocatalytic loop’ (energy invested to produce energy) and a ‘capital hypercycle’ (energy invested to maintain the means of turning energy into services).

Our current economic structure and resource dependencies ensure that we’ll burn a lot of fossil fuels to carry out a major shift towards renewable energy—a cost of the transition that we can’t afford to ignore. Among other things, this complicates discussions around the pace of the transition; it is not necessarily true that faster is better as large, short-term increases in fossil fuel demand for a renewable energy buildout may lead to significant excess capacity, wasting resources and frustrating the transition further down the line. Generally speaking, an ‘optimum’ timeframe in terms of what would limit greenhouse gas emissions or ecological impact will not likely align with the deadlines proposed to date by the advocates of rapid transition. Vaclav Smil notes that energy transitions on this scale typically occur over multiple decades or centuries, not years [6].

The manufacturing of silicon wafers in solar PV panels and advanced metal alloys in wind turbines requires a lot of high temperature heat, currently provided primarily by burning natural gas or coal.

Examining the energy system’s own metabolism also raises questions of residual non-renewable energy dependence that may be difficult to eliminate. The energy system’s autocatalytic loop and capital hypercycle are comprised of a mixture of energy carriers, meaning any attempt to shift the system towards a renewable basis will likely run into limits (due to energy carriers required to support the energy system not likely to be produced at scale via renewable means). For example, the manufacturing of silicon wafers in solar PV panels and advanced metal alloys in wind turbines requires a lot of high temperature heat, currently provided primarily by burning natural gas or coal. Will it be possible to run solar PV panel and wind turbine production lines using solar- and wind-generated electricity in the future? We don’t know, but there are reasons to be skeptical [7]. How about all of the remote access roads, transmission towers, substations, and supply depots required to create a renewable energy infrastructure? And the rare-earths, lithium, copper, iron, coltan, cadmium, and vast quantities of other minerals needed for the renewable energy buildout? It is hard to see how all of this can subsist on renewable energy flows alone.

Electricity

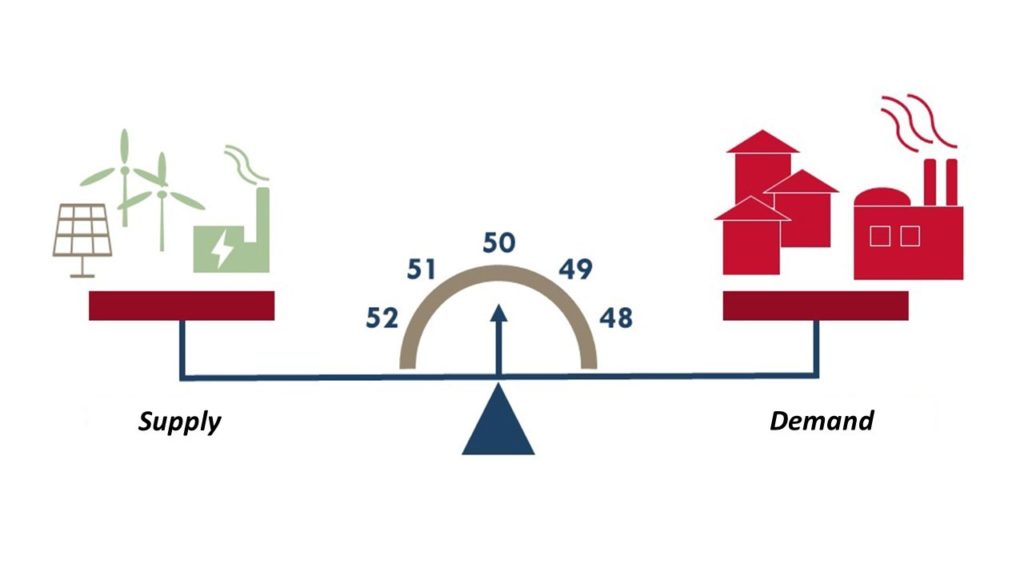

And then there’s electricity. Electricity is not like the other energy carriers in one critical sense: it is not a physical substance that can be produced and set aside for later use. In effect, this means supply must match demand at all times in order to maintain the stable, functioning electrical networks that distribute electricity to end users. Demand is stochastic—it changes as industrial production ramps up and down, and more erratically as households turn on or off light switches, run appliances, or do anything else that uses electricity. Consequently, supply must be ‘dispatched’ to meet demand on very short timescales as any temporary gap leads to changes in system frequency and large gaps can cause blackouts and damage vital electrical equipment (illustrated below).

The key problem with most renewable electricity production (including production from solar and wind) is that it is intermittent and can’t be counted on when it is required most. Electricity systems needs to retain the ability to meet demand when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. There are ways to maintain this ability as the share of renewables increases, such as building enough spare dispatchable generation capacity to act as a backup (often gas- and coal-fired) or building storage and additional transmission capacity. All have significant costs, in both energetic and monetary terms, and face their own social and technical limitations. For example, while there is much discussion around building better batteries to unlock renewables, this is still an exceedingly expensive option that is suitable only for shorter timescales, not the summer to winter supply-demand gaps creating most of the need for system flexibility [8]. Returning to our diet analogy, pinning all of our hopes on storage is a bit like asking a someone to put on 300 lbs every fall to survive the winter months with very little food. We wouldn’t expect a human being to be capable of this for very long and the odds of the energy system pulling off the equivalent feat are not much better.

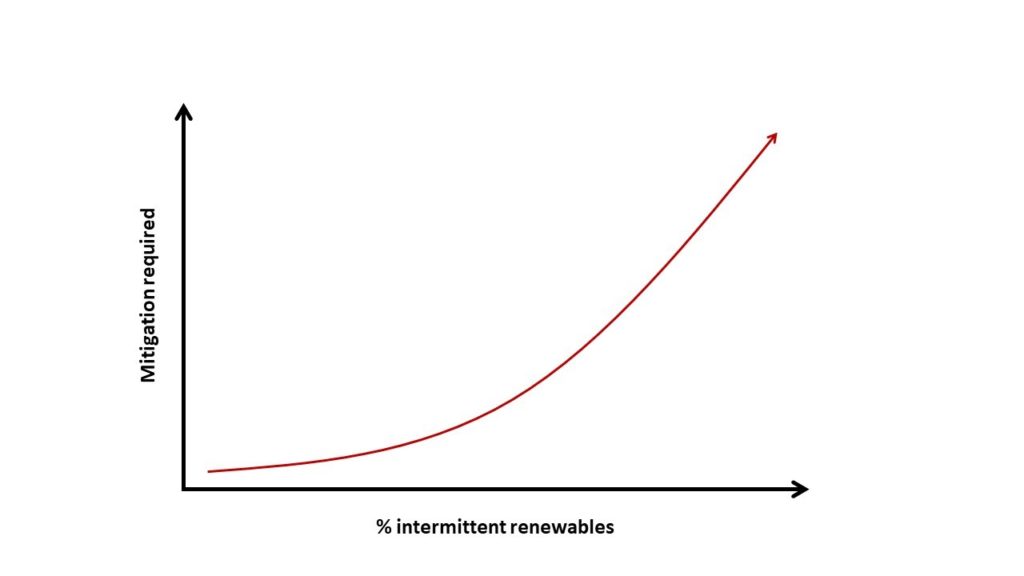

This difficulty only increases as renewables provide a larger share of total electricity. Figure 4 below shows how the mitigation investment required to maintain stable electricity grids increases non-linearly as the share of intermittent renewables grows [9, 10]. Technical and economic limitations in the electricity sector will manifest during any large-scale transition to renewable energy. Aside from a few fortunate regions with abundant dispatchable renewable energy resources (geothermal in Iceland, hydropower in Nicaragua, etc.), with current technology, this ceiling is far below the aspirational 100% renewable goal of the GND. The importance of these electricity system barriers is underscored by the fact that the provision of many of our energy services will need to be electrified in order to align with the growth of renewable energy.

Figure 4: The level of mitigation necessary to maintain stable electricity networks increases exponentially as intermittent generation rises

A story of limits

The crux of the problem is this: renewable energy typically produces forms of energy that are poor substitutes for the energy required to manufacture, transport, install, and operate renewable energy, at least without major investments into each stage of our energy system, significantly reducing or even erasing the net energy delivered. As such, these energy sources are dependent on the existing system and function less as a replacement for the fossil fuel economy and more as a temporary extension of it. The empirical evidence agrees—renewable energy investment does a poor job of displacing fossil fuels [11]. Of course, there are exceptions (such as traditionally produced biomass), but these have nowhere near the potential scale required to run today’s enormous globalized, industrialized economy.

Wherever the existing limit lies on the path to a 100% renewable energy system, we can and should push this limit through changes to consumption behaviours on the part of both industries and households, through things like shared utilization of end-use capital and energy services (think communal kitchens), a shift away from currently preferred but inefficient types of end-use capital (e.g. prioritizing public transit and micromobility over cars), greater alignment of demand to match intermittent supply, and overall demand reduction. However, it is precisely these kinds of changes which are more difficult to motivate, especially among those following the second narrative described above who may assume that high-energy, fossil-fuelled lifestyles represent ‘the good life’. Even at the extremes of practical behaviour change, the 100% target may still be unattainable.

Leaving aside the narrow concept of limits, a fundamental change in our energy basis and socio-metabolic regime would mean becoming a very different society from the one we know today. It is tempting to opine on our society’s wasteful habits and ask how much energy we really need, but the answer depends largely on the type of society we want to live in. Do we want to be able to build smartphones? How about MRI machines and water treatment plants? We may not be able to pick and choose what we want to keep from varying levels of socio-technical complexity (while it is certainly worth discussing what we might want to keep and what we can afford to lose). There is no demonstrated historical tendency for complex societies to voluntarily downshift their energy consumption on a large-scale [12].

When politicians and activists say “we have the technology” they vastly understate the challenges, potential barriers, and ultimate consequences involved in the transition.

The main point here is that the prospects and implications of shifting toward renewable energy extend far beyond present-day cost-benefit calculations, political maneuvering, or waging war on climate change. When politicians and activists say “we have the technology” they vastly understate the challenges, potential barriers, and ultimate consequences involved in the transition.

Raised stakes and political pushback

By forcing extensive change into an expedited timeframe, the GND raises the stakes and reduces the margin for error in the transition to renewable energy. If such a policy package were embraced, people everywhere would be subject to dramatically increased risks of misallocation of resources, misalignment of capacity between the various stages within the energy system, and of consequent economic and social fallout. The calls for radical action motivating the GND stem from a sense of desperation in the face of increasingly dire predictions regarding converging climate and ecological crises. That desperation is certainly justified, and yes, time is not on our side, but we must not dismiss the existential risks of a poorly executed GND.

The GND makes some very big promises and displays unmistakeable utopian elements. The problem is not so much the aspirational decarbonization goals, but the assurances of prodigious social benefits assumed to be attainable through or while pursuing them. Universal modern healthcare and higher education, job guarantees, raised minimum income, the elimination of poverty and inequality, significantly increased taxation of the wealthy—these goals proved elusive even during the period of greatest stability and economic surplus the world has ever seen. To achieve them during what will likely be a period of profound and growing ecological disruption, climate instability, and social unrest is rather optimistic to say the least. We will need to walk a long tightrope, balancing the pace of change, unforeseen challenges, impacts on communities, and necessary sacrifices. Perhaps the most dubious aspect is the overall ethical shift underscoring the kind of social cohesion necessary to achieve the GND in developed nations, from hyper-consumerism to environmental stewardship and the voluntary curtailment of discretionary consumption—essentially expecting everyone to spontaneously drop any differences of opinion and embrace the first narrative.

Owing to the existence of embedded conflicting perspectives, the GND will always have its opponents. Assuming we go ahead with it, any unintended consequence or local failure (of which there will be many) will be met with a backlash that risks eroding public confidence in the GND. This is a dynamic heightened in direct proportion to the level of ambition the GND embodies; the more utopian the stated goals, the starker the underwhelming reality, and the greater the negative reaction will be. How would we maintain broad political support for the GND, given the inevitability of broken promises? It may be that some of these promises need to be tempered against the requirement for achievable goals. A prime example can be seen in the German Energiewende, a planned national energy transition initiated in 2010 aimed at phasing out coal and nuclear energy. Promises of clean, renewable, reliable, and affordable energy clashed against the reality of Europe’s highest power prices and unconvincing progress on decarbonization [14]. This failure dampened public enthusiasm and made other countries hesitant to follow Germany’s example. The GND must learn this lesson—to promise more than you can deliver is to ensure failure.

There isn’t one unique, unambiguous end point to travel toward in response to the challenges we face.

One might reasonably ask whether too much ambition is really a weakness. Isn’t it better to have highly aspirational goals, even if they aren’t achieved, if only to carry us further than we would have gone otherwise? Well, not necessarily. It is important to note that there isn’t one unique, unambiguous end point to travel toward in response to the challenges we face. Time and our capacity for change are both limited. A last-ditch, herculean attempt to rebuild modernity anew would forestall the pursuit of other more credible and beneficial models of development.

First things first

So is the GND a good idea? Unfortunately, not in its present form. Given current levels of understanding of the complexities and trade-offs involved in a transition to renewable energy, and inflated expectations of future energy consumption, it would almost certainly result in a catastrophic failure. However, if guided by 1) an accurate and realistic understanding of the role of energy in society and 2) a willingness to honestly confront the profound socio-economic implications of a shift to a renewable energy basis, a reformulated GND might be able to point our global system toward a more sustainable paradigm.

Here are some additional principles for a truly transformative GND that I would propose:

- Energy literacy: energy transition is at the heart of the GND and its current assertions in this area are highly questionable. As such, there is a pronounced need for energy literacy, both in policy formulation and post-implementation general education. This energy literacy is needed to disarm simplistic narratives and enable transformative thinking.

- Demand side adaptation: to help bridge the gap between ambition and feasibility and unlock energy transition to the extent possible, the GND must embrace a radical rethinking of expectations for energy consumption. This must include overall demand reduction, but also greater demand flexibility, shared utilization of energy services, and shifting away from inefficient modes of energy service provision. Supply side interventions won’t cut it, we need to talk about the energy we use as a society.

- Evolving timeline: a complex, socio-metabolic process cannot be forced to conform to arbitrary deadlines and attempting to do so serves only to lock in unintended, suboptimal outcomes in terms of what we really want to achieve. The GND must abandon its stated 10-year timeframe and instead incorporate an informed, contingent, and evolving target for the pace of the transition.

- Political realism: assuming a forthcoming, sweeping alignment of perspectives on energy and social issues and subsequent unilateral action, as if in a political vacuum, is simply wishful thinking and must be rejected. The GND’s overall strategy must remain mindful of contrary narratives and the political pitfalls of excessive ambition. There should also be more discussion on who—from movements like Extinction Rebellion to environmental justice groups—can build the necessary political power for a truly transformative GND and how.

- Epistemic openness: new approaches are needed to navigate radical uncertainty and conflicting socio-technical narratives regarding energy transition. The GND must engage fields like Post-Normal Science—an approach to scientific decision-making for issues where “facts are uncertain, values in dispute, stakes high and decisions urgent” [15, 16]—as antidotes to reductionism and ideological echo chambers.

As a parting thought, ‘deal’ may not be the appropriate language given an overwhelming level of uncertainty. How can a deal be made and subsequently serve as the benchmark of success when the most relevant details are not yet known? In place of the GND, we might be better served by scaling back our ambition and embracing a Green New Direction. This alternative could preserve many of the same essential goals, but would need to forgo the use of enticing promises to motivate action and instead do the hard work of building solidarity and commitment to collectively face an energy future which will be more complex, more unpredictable, and more challenging than anything we’ve previously encountered.

References

- White, L.A., Energy and the evolution of culture. American Anthropologist, 1943. 45(3): p. 335-356.

- Krausmann, F., et al., The Global Sociometabolic Transition. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2008. 12(5-6): p. 637-656.

- Haberl, H., et al., A socio-metabolic transition towards sustainability? Challenges for another Great Transformation. Sustainable Development, 2011. 19(1): p. 1-14.

- Giampietro, M., K. Mayumi, and A.H. Sorman, Energy analysis for a sustainable future: multi-scale integrated analysis of societal and ecosystem metabolism. 2013, London, UK: Routledge.

- BP, BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019. 2019, BP. p. 64.

- Smil, V., Energy transitions : history, requirements, prospects. 2010, Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Moriarty, P. and D. Honnery, Can renewable energy power the future? Energy Policy, 2016. 93: p. 3-7.

- Carbajales-Dale, M., C.J. Barnhart, and S.M. Benson, Can we afford storage? A dynamic net energy analysis of renewable electricity generation supported by energy storage. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014. 7(5): p. 1538-1544.

- Heard, B.P., et al., Burden of proof: A comprehensive review of the feasibility of 100% renewable-electricity systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017. 76: p. 1122-1133.

- Trainer, T., Can renewables etc. solve the greenhouse problem? The negative case. Energy Policy, 2010. 38(8): p. 4107-4114.

- York, R., Do alternative energy sources displace fossil fuels? Nature Climate Change, 2012. 2(6): p. 441-443.

- Smil, V., Energy in world history. 1994, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Cai, T.T., T.W. Olsen, and D.E. Campbell, Maximum (em)power: a foundational principle linking man and nature. Ecological Modelling, 2004. 178(1): p. 115-119.

- Schiffer, H.-W. and J. Trüby, A review of the German energy transition: taking stock, looking ahead, and drawing conclusions for the Middle East and North Africa. Energy Transitions, 2018. 2(1): p. 1-14.

- Funtowicz, S.O. and J.R. Ravetz, Science for the post-normal age. Futures, 1993. 25(7): p. 739-755.

- Tainter, J.A., T. Allen, and T.W. Hoekstra, Energy transformations and post-normal science. Energy, 2006. 31(1): p. 44-58.

Tim Crownshaw is a PhD Candidate in the department of Natural Resource Sciences at McGill University in Canada and a student in the Economics for the Anthropocene (E4A) research partnership. He studies global dynamic transition pathways from non-renewable to renewable energy resources using quantitative, systems-based modelling approaches.