by Leah Temper

This speech was presented at the United Nations General Assembly on 23 April, 2018, as part of the Eighth Interactive Dialogue of the General Assembly on Harmony with Nature.

Sea levels are rising, fish stocks are depleted, temperatures may climb by 6% this decade. Inequality between us is growing, with the richest 1% owning half of global wealth.

We all know this so I won’t repeat it. Instead I would like to propose a collective thought experiment. Let us imagine that in this assembly that unites delegates from all the human nations of the world, delegates from the non-human world were also here with us. Let us welcome the delegates from the Animal nations, the Plant nations and the Rock nations. While we may not understand their language, let us try to listen to their claims and to hear their interests.

In this task we have of course much to learn from Indigenous communities in Turtle Island and elsewhere who have maintained such relationships with other life-forms for millennia. Nishnabeg scholar Leanne Simpson writes about how twice yearly “the fish nations and the fish clans gathered to talk, to tend to their treaty relationships and to renew life”. Their treaty included principles such as: take only what you need, waste nothing, respect cycles and seasons, and return fertility to the soil. These relations are founded on responsibility and reciprocity and ensure the health and flourishing of both parties.

We are here today in commemoration of Earth Day to discuss how we can rebuild these relationships with the community of life. How can we transform our systems of production and consumption in harmony with nature and other humans? How can we move from extraction to restoration? From overconsumption to reproduction? From domination to care? What would an Earth Jurisprudence economy look like?

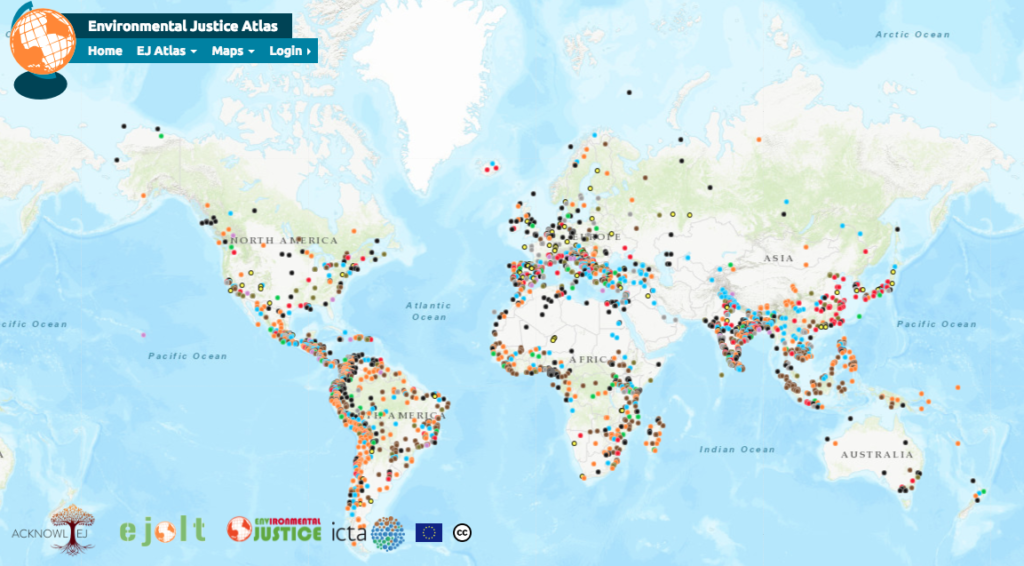

Over the past 10 years my work has entailed examining these questions through the experiences of those defending the environment and their health and livelihoods. We have been collecting these stories in the Global Atlas of Environmental Justice (http://www.ejatlas.org), a participatory project which maps protests and mobilizations against life threatening extractive activities around the world. To date we have documented 2400 such ecological conflicts. Environmental justice includes the right not to be polluted, to have a safe environment to live, work, and play. It also includes justice for the greater web of life, acknowledging the inseparability between justice for nature and justice for humans.

This work has brought me to some of the most polluted and to some of the most pristine places on the planet, to the barricades with communities blocking pipelines, Indigenous groups defending sacred mountains against mining, pastoralists opposing land-grabbing, and recyclers fighting incinerators that would burn the waste they depend on. While some dismiss these communities on the frontlines as anti-development, they are stepping in and resisting because they feel their leaders are not taking the necessary actions. They often can’t be bought off, but are putting forward a vision for a radical transformation of our societies and economic system while engaging in experiments in diverse ways of living and new forms of collective organization.

Their call for systemic and structural change is not addressed in the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, which fall short in arresting the driving forces that cause poverty, such as wealth concentration, corporate control and impunity, and ongoing racism and colonialism.

We know that the current economic paradigm constrains our ability to tackle these forces. Economic growth, resource efficiency, and the green economy cannot address the poverty caused by environmental damage and the commodification of life. Ecological economics, which is an economics grounded in biophysical reality that respects the laws of thermo-dynamics, rejects the possibility of limitless economic growth on a finite planet. We must acknowledge that the economy is embedded in nature and its expansion will always require fresh resources and new sinks for wastes. Thus the need to continually colonize new areas for extraction and waste disposal, leading to conflicts, environmental degradation and increased inequality. We must abandon growth because pursuing it mindlessly instead of focusing on equality, distribution and justice is a driving cause of poverty, not a corrective to it.

The good news is that a new paradigm is already emerging and citizen movements, North and South, as well as governments are already thinking beyond growth.

The good news is that a new paradigm is already emerging and citizen movements, North and South, as well as governments are already thinking beyond growth. There is a growing international movement for de-growth which argues that those countries who are occupying more than their fair share of environmental space must downscale production and consumption but that they can still increase human flourishing while devoting more time to nature, culture, and community.

Above you can see the Global Atlas of Environmental Justice. Each dot represents one case where the community has risen up to say we refuse to be polluted, we don’t want that mine, that highway, that nuclear power plant in our community. I invite the reader to go to the atlas and to see what is happening in your countries. The data is not complete, but it gives us a broad picture of who suffers the impacts stemming from the underside of economic growth. And it is primarily women, Indigenous communities, peasants, fishers and other marginalized people who are being polluted and dispossessed. While sometimes referred to as minorities, they represent the majority of the world’s and your countries’ populations. They do not all want to follow a single path to development. Together they constitute a global environmental justice movement.

The atlas also shows that it is possible to stop these life-threatening activities. That it is possible to find billions of barrels of oil in the ground and leave them there. There is the case of the Te Urewa Park in New Zealand. El Salvador, in consultation with the rock and water nations, has put in place a ban on metal mining under the world’s first such moratorium. Costa Rica, in defense of the plant and animal nations in that mega-biodiverse country, has decided that fossil fuel extraction is too great risk for their collective health and put in place a moratorium. France, Quebec, and Tunisia and some other territories have banned fracking.

What if instead of economically recoverable reserves of minerals we talked about ethically recoverable reserves? To reduce the risk of catastrophic climate change most fossil fuels reserves have to be kept underground. These unburnable fuels include 80% of coal, 50% of gas and 30% of oil. An Earth jurisprudence economy would include policies and laws to halt extraction of these reserves for both local and global well-being. An Earth jurisprudence economy would accept that there are places on Earth that should not be ripped open by mines or bulldozed for highways no matter the potential profits.

One path to restructuring our economy in harmony with nature is to shift the emphasis from production of things to the reproduction of life. A central element of this transformation is recognition of what has previously been considered free of charge and available for exploitation—the reproductive and care labour undertaken primarily by women, and nature’s gifts including air, water and soil fertility.

Reproductive labour includes work in the home, child-care but also the work of peasants, fishers and Indigenous peoples who work directly with nature to meet the everyday needs for the majority of people on Earth. This work, done mostly by women, is integral to the functioning of our economies and yet it is primarily unpaid and unrecognized. A new report estimates the value of unpaid childcare to Australia’s economy at $345 billion making it the single biggest sector. As the mother of a 5-month old newborn I can assure you that breastfeeding is a full time job on its own.

An Earth jurisprudence economy, instead of producing more consumer goods, would invest more resources in teachers, nurses, mothers and other care-workers.

An Earth jurisprudence economy, instead of producing more consumer goods, would invest more resources in teachers, nurses, mothers and other care-workers. Farmers would not be pushed off their lands to make way for industrial plantations. They would be supported to continue working alongside the Plant nations, Insect nations and the Soil microbe nations to feed 70% of the global human population while increasing seed and agro-biodiversity, and cooling the planet.

Yet it’s true, in an economy with less extraction and less consumption, there would be less jobs in some sectors. This is a concern. Yet instead of more consumption to remedy this, what if we began rethinking work? This would include diverse initiatives. Pilot studies such as one in Iran show that when guaranteed an unconditional basic income, workers don’t work less, instead they explore work that they want to do and is in line with their values and goals. They seek work which allows them to be creative, to improve their communities, to problem solve collectively. These are the jobs of an Earth jurisprudence economy.

I began this essay asking us to acknowledge the presence of the Animal, Plant and Rock nations with us in this room. My hope would be that henceforth politicians continue to include these nations in their thoughts and deliberations. But let’s remember that since these nations cannot speak, we must listen to the human voices who speak on their behalf. In closing I would therefore like to acknowledge those who dare to speak out for our more-than-human nations. Above you will see some of their faces. These are all environmental defenders killed in the last year murdered for their defense of the planet. According to Global Witness, four environmental defenders were killed per week in 2017.

I would like to applaud the recent regional Latin American and Caribbean Escazu accord which guarantees the right of environmental human rights defenders to carry out their activities without fear, restrictions or danger. This agreement will be open for signatures here at UN headquarters in September. I would urge world leaders to put forward such an initiative for all members and to ensure compliance. We are here to talk about living in Harmony with Nature but the reality is that we are murdering those who aim to defend life.

The journey towards an Earth jurisprudence economy, rather than being seen as an insurmountable challenge, can serve as a uniting force in our defense of the global commons. It can reawaken an ethic of care, reinforce livelihoods and create meaningful work. In these times of great divisions, the protection of our shared home can serve as a convergence issue where we can jointly challenge multiple forms of oppression, including racism, sexism, speciesism and violence and where new solidarities and new worlds can be born.

Leah Temper is a trans-disciplinary scholar-activist based at the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology (ICTA) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. She is the founder and co-director of the Global Atlas of Environmental Justice (www.ejatlas.org) and is currently the principal investigator of ACKnowl-EJ (Activist-academic Co-production of Knowledge for Environmental Justice, www.acknowlej.org) a project looking at how transformative alternatives are born from resistance against extractivism.