by Mel Evans

The Government has concluded that it does not see a strategic case to bring forward a tidal energy scheme in the Severn estuary at this time, but wishes to keep the option open for future consideration

– British government, 2010

The project anticipates that the Bristol area will likely experience a sea level rise of 7m by the year 2275

– Alfie Hope, Sea Rise City art project in collaboration with the UN department of Water and Climate Change, 2015

One of the most urgent tasks that we mortal critters have is making kin, not babies

– Donna Haraway, 2016

Were I a man, or had I a woman as partner, I might have made very different choices about marriage and children

– Rebecca Solnit, 2016

The rain was light, but effective in its endeavour. The unwaxed fabric of the marquee roof was starting to give in to the pressure above, and beads of liquid formed and dropped on the sombre faces of the huddled gathering like teardrops. Oh well, thought Esta. Water is a core element of the ceremony.

Esta loosed her attention from the preparatory notes that Mera, the officiant, was delivering to her friends, family and colleagues. Although attentive, they were more focused on playing their parts in this just-familiar ritual than they were on what this might mean for Esta herself, the initiate. Had her mother been honest when she described this as a happy day for all the family, or was she merely playing a new role? Esta wondered if her choice was really worthy of this hub of support and celebration.

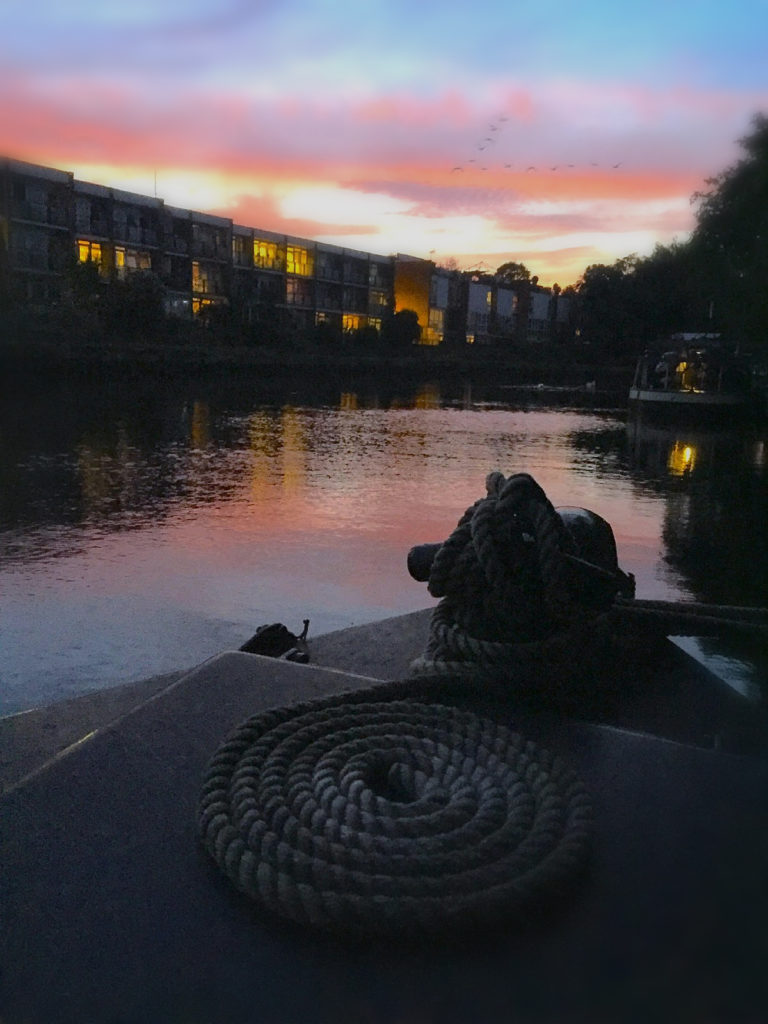

She looked over the valley at Avon, both town and river of the same name. For half the year the town was the river and the river was the town, for the bounds of the waters surged dramatically from the dry to wet seasons. With the season of Iver finally drawing to a close, the waters were due to subside, and Esta had hoped today might offer the first signs of Estate, the season for which she was named, and with it, some sun. But no, hopefulness and horizons were not to be hers today it seemed. Instead a weary grief flowed from the clouds.

Where Avon’s waters brought power and plenty, they also continually took more land and homes.

In the years since the Division, Esta found hope and loss to be increasingly contingent: avenues explored and dead-ended. Possibilities denied and resolve found only in their void. Where Avon’s waters brought power and plenty, they also continually took more land and homes, making stilt-house residents keen to reach ever-higher ground, and making all citizens cautious of the transient valley. Her own boat-home sufficed whatever the shoreline level, but the waters calmed the lower they flowed.

Mera now stepped closer, drawing Esta’s gaze away from the skyline of boat-decks and rooftops above the waters and back to the fountain at the centre of the marquee.

“It is now. The moon has come through. The meeting of light and dark begins.”

Mera offered Esta and the others glasses of the red wine that poured from the fountain, imported from the neighbouring country of Greater Thames no doubt. It was meant to signify the last blood tasted and lost. Esta’s parents were given chocolates, a condolence of sorts, for where the ceremony was meant to be celebratory for her and the many other women who underwent the Commitment, there was no forced suppression of the grief at the loss of a matrilineage that is felt by many parents when their daughter’s time comes. Esta’s own mother had not been offered this opportunity to choose between having or not having children, and Esta had so far failed to ask how she might have considered it.

Mera pressed her forehead to Esta’s, and she awakened to her own presence in the ritual. She felt herself surfacing from below water, from the darks of a river pool into the light of a bright moon. She had chosen this path, and now it was carrying her forward into territories unknown. Mera poured water over their hands and faces from a silver pewter jug engraved with Sheela-na-gigs, a sexuality goddess mistaken as fertility queen from millennia past in the region. Together they began the incantation:

Of fruit that bears seed

Will now the tender corn yield

Of fruit that may flower

Comes now the greater power

All men now find femme

Parental duality within them

For my country’s greater need

I shall not breed.

Hearing her friends speak the words before had half-shocked half-thrilled Esta. It was as if the women became more powerful in rejection of their natural potential to bear offspring than in its enactment, like lionesses refusing to eat a kill. Power withheld is more potent than strength spent. Yet in this moment, giddy with the first alcohol she’d tasted in months, a deeper pain stabbed her from inside, and she didn’t find herself exuding the empowered grace she’d been told to expect.

She glanced at Yannick, once her lover, who was at that moment tending to his belligerent toddler alongside his partner Khalil.

She glanced at Yannick, once her lover, who was at that moment tending to his belligerent toddler alongside his partner Khalil, a cooing calamity erupting from the warm glow of their familial cocoon. Esta wondered whether the sharp pang she felt high in her chest was for Yannick himself or for what he shared with Khalil and their son. Ever since the Division which split Greater Thames, Avon, Mercia and Cumbria into separate countries, Avon and its shires had been declared formal matriarchies. In practice, however, it was wealth not gender that determined power and influence at the very top, just as before.

The reformation into a matriarchal society came in defiance of the further entrenchment of patriarchy in Greater Thames. When the richer, more powerful Greater Thames cast the rest of the island off from its financial prosperity, the regions-turned-countries sought to define themselves in the negative image of their former ruler. Mercia and Cumbria were now ruled by farmers and miners; Avon was ruled by women, who were mainly engineers. In this matriarchy, the decree that men must nurture and bear full responsibility for child rearing had initially been seen as a rebalancing of respect for care work, one which suited men like Yannick and Khalil who were already partnered in the eyes of the state under the old systems. But Esta, who had not partnered in that way but navigated brief intimacies with women she met through work, or men who lived around her moorings, increasingly felt the men basked in a greater glory for their parenting than ever afforded to women in the past.

Her own parents embraced the change willingly but not wholeheartedly, happy that their only daughter would rise in the ranks of her profession. The decision to employ only women in all areas of public works had proved successful for the recovering economy, post-Division. The female workers remained more efficient, even on better pay, and productivity was unprecedented. Esta was proud of the contributions she had made to the overhaul of energy production following the total destruction of their offshore renewable power infrastructure in the 24 hour military attack by the States some twelve years ago as punishment for Avon’s refusal to sign a trade deal. The ten years since Esta had graduated as an engineer at the age of 17 had scattered around like leaves in a gust of wind, butterflying her from homestead power to geo-thermal projects across the city.

Water-power had its season, and solar likewise, and it was her designs that helped bridge the transition from the lifestyle and rhythms of energy use that went with one generative source to the next. Still, getting power to the outer reaches of the shires was hard outside the protections of the town. In the shires, local transmission was not an option and infrastructure had to be imported, risking theft en route by the smugglers feeding the insatiable hunger of the elites in Greater Thames. Having spurned the regions lack of economic contribution it was joylessly ironic to see what was once a self-sufficient capital city rely on the resources of neighbouring countries via the smuggler’s market.

Esta swallowed the last blood-red drops in her tin cup. A cloying aftertaste remained, sticky as bloodied knickers and used condoms, the trappings of which she’d now have no need. Women still took male lovers, although many men chose to parent. Those men that did not had no prospect of public work since parenting was only an option supported by the state if within a long-term partnership with another man. The ones that chose not to parent lived productively, but quietly, hosting events for workers, tending to small-scale farming and other arts. Theirs was a quiet masculinity which neither translated to Avon’s new traditions nor maintained power in the old ways.

With a façade of the initiate’s readiness for change, Esta mimicked Mera moving along the line of guests echoing the codes of the republic with each of three kisses on the left cheek, “Independence. Productivity. Sisterhood.” The same words screamed at political rallies in years past, now hollow with repetition instead of bursting with resistance. When she reached Yannick in the line, the flushing weight of the wine in her face forced a pause and she accepted his steady gaze.

“You’re scared Est. It’s ok.”

His squeeze of her shoulder was too tempting a warmth in the cool air, which was drawing heat from her skin as the evening closed in and the rain crescendoed.

“It’s not the operation…it’s the expectation. Like I’ve got to fill this supposed void with a thousand other achievements.”

“You’d do everything you do either way. This should be about what you want, not what’s expected of you.”

She thought of all she’d worked for over the past decade of political upheaval.

“All I expect is another surprise.”

Mera had reached the end of the line, her eyes calling Esta onwards, closer into her new self. Her mother’s kiss, the last in line, was simple and forgiving, unquestioning of any choice Esta made with the body she had birthed to her. Suddenly Esta longed to more fully understand the gift her mother had given her. The carriage, effort and majestic trauma necessary to create her own being. This would be an appreciation she could never truly know without sharing in its drama. From a frail emptiness at the base of her spine came a new determination, like a resurgent kite striking high in the sky on a fresh wind. The incantation Mera began breathed into this space inside her.

A new role

A new body

A new meaning

The female eunuch revisited

In sexless, seedless, flowerless power

From milk and honey to muscle and mind

We loose the limits of your body

Upon you.

Elsewhere in Greater Thames at this very moment, women her age would be celebrating pregnancies and embracing the charms and challenges of a life involuntarily devoted to motherhood.

Elsewhere in Greater Thames at this very moment, women her age would be celebrating pregnancies and embracing the charms and challenges of a life involuntarily devoted to motherhood, prohibited them from any other form of work until the children were 17. Where in Avon parenting was a male duty, in Greater Thames women bore the labour alone, but without glory or credit, simply out of custom and expectation.

Esta recalled the look of condescension and disbelief in the eyes of her colleague’s father during the only ever trade visit to Greater Thames when she told him her and her friends were not, nor did they intend to become mothers. In that moment she held his first grandson at six weeks, his latent fear that her inexperience might at best hurt the child and at worst curse him. She herself was sure the baby quieted like a trusting puppy at her lack of panic about being perceived as a failed woman, palpable in the new mothers present. There was so much expectation on them, yet no emergence in success. Could it be that women on both sides of the border, whether esteemed as mothers or matriarchs were doomed to feelings of perpetual insufficiency? She looked to her own mother once more, and felt the familiar reassurance of her knowing gaze: neither route provided assurances.

The rain had begun in earnest now, and pounded on and through the cloth roof, already soaked and heavy with uncertainty and expectation of waters breaking. Esta’s eyes set on the red tent awaiting her across the hilltop where they stood. Mera’s slender fingers were holding back the curtain from within. It was time to wave goodbye to the possibility of an unworkable surprise. She hugged Yannick one last time, absently kissed his baby’s forehead, and headed down the slope towards the red tent’s opening.

Mel Evans is an artist and activist. Mel has written one non-fiction book (Artwash, Pluto, 2015), contributed to various academic journals and books, and had several pieces of creative writing published (A Woman Alone, with The Dangerous Women Project and poetry in the Poppies edition of Brain of Forgetting).

This piece is part of Not afraid of the ruins, our series of science fiction and utopian imaginings.

To receive our next article by mailing list, subscribe here.