by Ekaterina Chertkovskaya and Alexander Paulsson

Lately there has been a rising interest in degrowth – an umbrella term that critiques the centrality of economic growth in our societies and embraces various alternatives for ecological sustainability and social justice (see Kallis et al., 2015). This interest is shared not only by the proponents of degrowth, but also its critics, who often support many of the ideas behind degrowth, but have reservations about using the term.

It seems to us that these reservations at least to some extent arise from economic growth itself being an ambiguous and contested concept. For example, Kate Raworth suggests that it is not clear whether degrowth refers to the decrease of the economy’s biophysical throughput or its monetary value, measured in GDP, and argues that the difference matters. Or, John Bellamy Foster proposes that it is important to argue not “for degrowth in the abstract, but more concretely for deaccumulation – a transition away from a system geared to the accumulation of capital without end.”

These reservations about degrowth point to the need to clarify what growth traps to avoid when making a transition to sustainable degrowth. In what follows, we articulate three ways of understanding growth that should be challenged by degrowth: first, reliance on biophysical throughput; second, capital accumulation and productivism more generally; and third, the perpetual strive for quantitative expansion of national economies (measured in GDP). We also propose that growthocene can be a suitable way to characterise the epoch we live in, broadening the notion of capitalocene while opposing the now mainstream notion of anthropocene.

Biophysical throughput

Economies across the world rely on growth of biophysical throughput, which has led to severe ecological consequences for Earth and its ecosystems. In contrast, degrowth would involve descaling biophysical throughput. This critique of growth has been partially integrated into the mainstream discourse, as captured by the notion of anthropocene. However, this concept is deeply problematic as it suggests that all human beings are responsible for the ecological crisis. Differences related to class, gender, race, geopolitics or economic systems themselves are glossed over or totally disregarded.

While renewables are of course an important way forward, the transition to them does not automatically lead to sustainability or justice.

Green economy has become a buzzword that is often suggested as a solution to the world’s ecological problems, whether by the left or right. Such an economy, however, is neither sustainable nor just because it focuses on incorporating (supposedly) green solutions into the economy with all its flaws and divisions rather than changing the economy itself. For example, the economic valuation of nature is green only on paper, in reality, it enables continuous ecological destruction and the appropriation of local governance (see Kill, 2015).

And while renewables are of course an important way forward, the transition to them does not automatically lead to sustainability or justice. For instance, in Brazil, the way the shift to renewable energy is implemented—on top of challenging the biodiversity of the Amazon—often threatens the very way of being of indigenous communities and the livelihoods sustained and inhabited by them (e.g. as the case of Munduruku Indians demonstrates).

So in striving for sustainability and justice, degrowth goes beyond the question of biophysical throughput and the physical limits of our planet. It would need to involve challenging the problematic and potentially harmful solutions positioned as ‘green’, such as the carbon and biodiversity markets or nuclear energy. This also would also require problematising how these proposals have been promoted under appealing banners like ‘inclusivity’, ‘poverty reduction’ and ‘development’. Therefore, it is crucial to ask questions like: ‘what is at risk?’; ‘who benefits and who loses from the proposed solutions?’. Pushing this line of thinking further, we must also ask what societal divisions, injustices and inequalities are maintained, reproduced or enforced by such policy proposals.

Capital accumulation and productivism

This brings us to challenging growth understood as capital accumulation. Not only are the conditions under which capital accumulation occurs demarcated by class, gender, race, and other divisions, but when surpluses are reinvested in the economy, these divisions become amplified. As has been powerfully observed by a broad spectrum of critical theories, such as anarchism, feminism, Marxism, and postcolonial thought, the strive for surplus accumulation relies on maintaining injustices and inequalities. Some of this critique has been captured by the notion of capitalocene, which suggests that capitalism, and not all humanity, is responsible for the ecological and also social problems we are facing (see Haraway, 2015; Malm, 2015; Moore, 2014).

The popular slogan ‘system change not climate change’, then, should imply not only a systemic change in the way we deal with climate or ecology, but in the very way our societies are organised. Degrowth also problematises these forms of accumulation, including, commodified consumption with a ‘sustainable’ or community-oriented appearance. For example, the notion of the sharing economy often commodifies social and communal spaces and depends on precarious labour conditions (see also Schor, 2014).

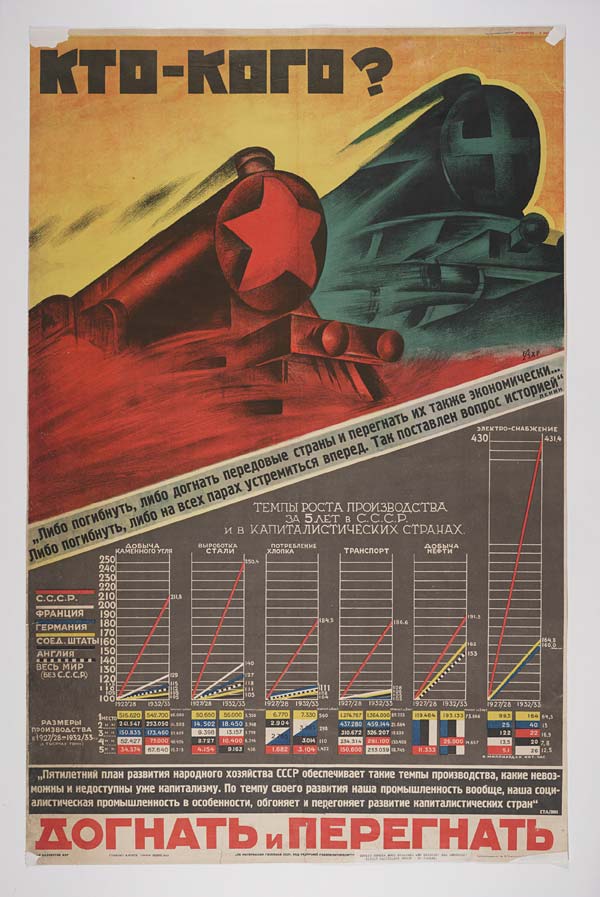

While capitalocene is a powerful idea to understand ecological and social problems without decoupling them, it does not capture the whole picture. For example, it struggles with how to grapple with the environmental history of the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, whose economic systems, too, had devastating ecological and social consequences. Industrial production was the key driving logic for organising these economies, if not in shaping their entire societies.

It is important to challenge not only capital accumulation, but more broadly productivism, that is, the growth of production as desirable in itself.

Therefore, it is important to challenge not only capital accumulation, but more broadly productivism, that is, the growth of production as desirable in itself. Apart from industrial production, this includes many other forms of production found in contemporary economies, such as production of information, knowledge, technology, and services.

However, it is also crucial to note that challenging productivism does not suggest descaling of all production as there are different types, ways, consequences and understandings of it. For example, it would be desirable to see more permaculture as a sustainable production practice in agriculture. Or the expansion of initiatives like platform cooperativism—as opposed to the ‘sharing economy’—would also be appealing to many.

In line with the argument that has been presented so far, we suggest using the notion of growthocene – i.e. the strive for perpetual growth—consisting of reliance on growth of biophysical throughput, continuous capital accumulation and productivism more generally—to describe the epoch we live in and the ecological and social problems we are facing. Degrowth, then, captures both the conditions and the consequences of the growthocene.

Quantitative expansion of national economies as measured in GDP

The perpetual striving for quantitative expansion of national economies is in line with prioritising production as desirable in itself, which is part of the growthocene. The assumption underlying this ideology is that quantitative expansion automatically leads to an increase in prosperity. Based on this assumption, GDP is being used as the dominant measure of the monetary value of national economies. It was introduced as a tool for the US government to deal with the Great Depression and then to plan production during the Second World War, but eventually became the central measure of almost every nation’s progress.

While degrowth is not aimed at shrinking GDP or the monetary value of the economy, we would also like to stress that degrowth should not be evaluated in light of GDP and similar measures as these are essentially flawed indicators of prosperity.

GDP and other similar measures, on top of being inadequate indicators of prosperity, have had problematic consequences. First, they produced a norm, which allowed countries with lower national incomes to be ‘analysed and framed in a way that suited their assumed future compliance with the industrialized model’ (Speich, 2011: 19). Second, gearing crucial public institutions—such as education and healthcare—towards increasing GDP has made them more exclusive and subordinated their core functions to economic demands.

So while degrowth is not aimed at shrinking GDP or the monetary value of the economy, we would also like to stress that degrowth should not be evaluated in light of GDP and similar measures as these are essentially flawed indicators of prosperity. GDP has been convincingly criticised by many scholars already (e.g. Fioramonti, 2013), but, due to its hegemonic status, this remains part of the task of degrowth as well.

Toward the notion of growthocene

To sum up, striving for growth – or the growthocene – is manifested in reliance on growth of biophysical throughput, continuous capital accumulation, and productivism more generally. Hence degrowth can be understood as descaling of biophysical throughput, deaccumulation and anti-productivism, and aimed at bringing together the alternatives that fit these principles.

Such an understanding does not decouple ecological and social problems. It acknowledges that capitalism bears a large share of the responsibility, but is not the only system that has led to the problems we face today. It also highlights that productivism itself is part of the problem and hence cautions against proposing solutions rooted in its logic.

A version of this article has been published in the blog of ENTITLE, a network of European Political Ecologists.

Ekaterina Chertkovskaya is part of the degrowth theme at the Pufendorf Institute for Advanced Studies and the Sustainability, Ecology and Economy research group at the School of Economics and Management, both at Lund University. She is also a member of the editorial collective of ephemera journal.

Alexander Paulsson is part of the degrowth theme at the Pufendorf Institute for Advanced Studies and the Sustainability, Ecology and Economy research group at the School of Economics and Management, both at Lund University. He is also a postdoctoral researcher at the Swedish Knowledge Centre For Public Transport.