by Srđan Tunić

This essay is the second in a “mini-series” of two essays on the critical potential of science fiction. The first essay considered how science fiction can function as social critique and discussed different literary techniques and devices. This second one will expand the story in reference to concrete examples—works by Enki Bilal and Aleksa Gajić, grounding the analysis in the Balkan context. (And if you continue reading to the end, there may be a surprise waiting for you there … )

In an article (“Vreme kao ključna odrednica SF žanra”) written in the midst of the Yugoslav Civil War (1991-1995), the Serbian science fiction (SF) writer Milovan Milovanović stated that most local SF stories seemed disconnected from the everyday situation of most people in the Balkan region at that time. According to him, in order for elements of novelty in SF stories to be accepted by readers, you need a realistic historical background and not just escapism. Even though SF imagines the future and diverges from the present, it always springs from specific places and histories (see also this chart of how historical trends in SF have changed over time):

For example, when the threat of nuclear war hung over the world during the 50s of this [20th] century, what else could the favorite topic for SF writers have been? Later on, at the beginning of the 70s, it was raising ecological awareness, due to the widespread knowledge that the world was mostly disappearing into a vortex of a biological catastrophe. This is not just related to the frequency of specific topics at specific times; it refers to a way of thinking that was totally different at the beginning of the [20th] century, the 40s, 60s, or today. The world today is not the same as it was five or ten years ago and that is strongly mirrored in SF literature.

Belgrade, as the capital of all versions of the union of South Slavs in the twentieth century, holds a prominent place in representations of state power and as a battleground for diverse imaginings of the future.

This is where Belgrade (and the Balkans in general) enters the story. Belgrade, as the capital of all versions of the union of South Slavs in the twentieth century, holds a prominent place in representations of state power and as a battleground for diverse imaginings of the future. This text will discuss its images and interpretations through two contemporary comic book authors working in the SF genre—Enki Bilal and Aleksa Gajić. Whilst the former has been based in France for a long time, with Yugoslav heritage, the latter lives in Serbia. Both feature Belgrade in their comics and films, and both work predominantly for the French market. The artworks in question are Bilal’s Bunker Palace Hôtel (1989) and Le Sommeil du monstre (The Dormant Beast in English, aka the Hatzfeld tetralogy, 1998-2007), and Gajić’s Technotise (comic, 2001) and Technotise: Edit & I (film, 2009).

The prominence of Belgrade as a setting in the authors’ works has been recognized by Gajić himself. In an interview with Deborah Husić from 2011 (in English), the use of Serbian language in the film Technotise: Edit & I was mentioned as one of the novelties (or what Darko Suvin would call novum), because, as the artist noted, “usually everything happens in Tokyo, Paris, Berlin or New York.” Aleksa Gajić responded that he did not want to make compromises for the market:

Usually, authors have this strong need to flatter the audience in order to be accepted. Meaning, they will answer to all ‘expected’ patterns from the public. As a matter of fact, most of the films we are watching today are made having these patterns in mind. I really wanted to run away from these things with Technotise. I wanted Belgrade to be like that, let them talk in Serbian, and let them express local jokes and natural urban expressions in an SF story (emphasis added).

Why are there no UFOs in Lajkovac?

SF was mostly associated with western geography and popular culture.

Zoran Živković, one of the pioneers of modern SF in Yugoslavia during the second half of the 20th century, famously stated that “leteći tanjiri ne sleću u Lajkovac”, meaning that UFOs do not come to a typical Serbian village. This came to be know among the sci-fi community as “Zoran’s law”. This metaphor indicates both that SF set in a local context was rare (or non existent) and that SF was mostly associated with western geography and popular culture (for a further discussion, check out Milovanović’s guide to SF, in Serbian). This, unfortunately, does not take into account contributions from the former USSR/Russia, or other non-western countries. In this geographical (or geopolitical) discussion the worlds of manga and anime, which originated in Japan but have spread to other parts of Asia, also play an important role today.

The world depicted and the context (reality) from which it departs (or reacts to) are tied together.

The lack of grounding in local history and settings—or the lack of UFOs in Lajkovac—pinpoints the escapist nature of many SF works of former Yugoslavia and Serbia. However, this “law” started to change in the late 1980s and early 1990s, simultaneous to the breakup of the SFR Yugoslavia (which is discussed in “Leteći tanjiri ipak sleću u Lajkovac” by Ivan Đorđević, and “American Science Fiction Literature and Serbian Science Fiction Film: When Worlds Don’t Even Collide” by Aleksandar B. Nedeljković). The example of UFOs in Lajkovac highlights two aspects of SF I consider relevant to this analysis. First, that SF narratives have their own internal structures and logic; and second, that there is a dynamic and productive connection to be made between a narrative and its author—and potentially between a narrative and its local historical and geographical origin as well. That is to say that the world depicted and the context (reality) from which it departs (or reacts to) are tied together.

This is closely related to the discussion in the previous essay, “Science fiction between utopia and critique,” of how authors can employ different perspectives and literary traditions—utopian, dystopian, alternative histories—to both imagine a different society and show a (critical) reflection of our own. With these concepts in mind, we will now look at the oeuvres of the two artists.

The dystopias of Enki Bilal

Enki Bilal’s work in general features darker SF topics and overtones, which could be identified as dystopian, often tackling issues such as totalitarian regimes (theocracy and fascism), colonialism, corruption, identity crisis, schizophrenia, and despair, but often with an ironic tone. A great source (in Serbian) on Bilal’s work is a special issue of the magazine Gradac, edited by Miroslav Marić; in the following, references to critical discussions and quotes from interviews with Bilal, unless specified differently, are derived from this special issue of Gradac.

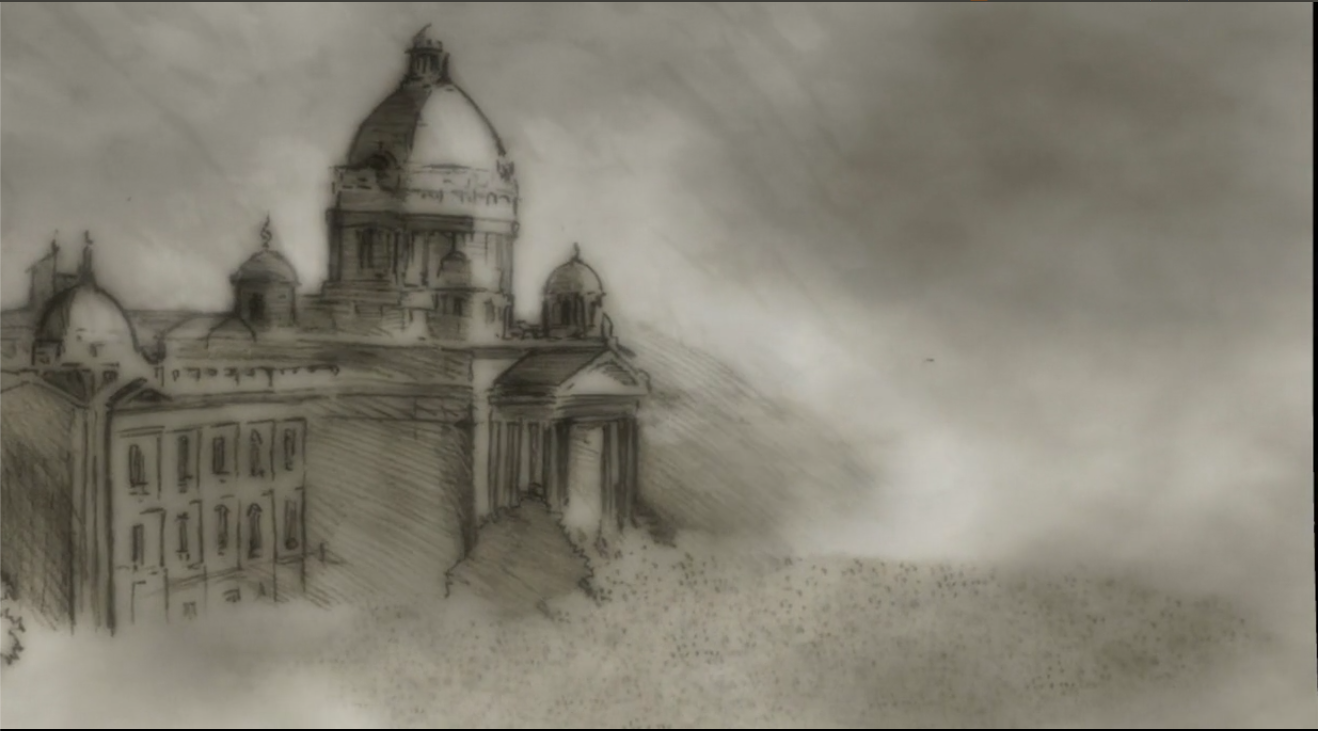

Bunker Palace Hôtel (1989) is the first feature film Bilal directed, co-written with his long time collaborator Pierre Christin. It is set in Belgrade in an alternative reality, or the no-time of uchronia, with a combination of French and Yugoslav actors, but targeting the French market. Some commentators characterize this film as a critique of the socialist regime in Yugoslavia (which Bilal has denied), as well as an announcement of the overall breakup of the Eastern bloc in Europe. Initially, Bilal wanted the film to take place in the USSR, with Belgrade as his second option. In an interview from 1988, he clarifies his choice:

If you insist, the film talks about a [political] system that mostly resembles fascism. I wanted the film, where one cannot see which country or time is in question, to be filmed in a somewhat oriental, extraordinary setting for the French [audience]. To have a bit of exoticism. And I am very happy to film here, because the Yugoslav actors contribute to that exotic impression.

He also incorporates a fictional Slavic language, used by the rebel characters, in this “exotic” feeling. People’s names vary between western and Slavic (Holm, Clara, Nikolai, Zarka, etc) however, there is no explicit naming within the narrative of the film of the rebels, the state, the city, languages, ideologies, nationalities or time. The film follows the SF trend of alternative histories (uchronia), with dystopian elements and an exploration of the question: What if the Nazis had won the Second World War (WWII)? (a question echoing in SF since Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle). If we accept this line of thinking, using the image of (the then) socialist Yugoslavia as a mirror/reference society becomes more complex and troubled.

Everything is retro, or “retro-futuristic”, which is a familiar setting within certain SF subgenres.

We need to understand the alternative history setting of the Bunker Palace Hôtel itself. Any reference to the then contemporary society is mostly avoided—cars, technology, architecture, clothing. Everything is retro, or “retro-futuristic”, which is a familiar setting within certain SF subgenres. In the film we can see well-known buildings from the pre-WWII decades, such as eclectic, art nouveau and modernist architecture: mainly the French Embassy, Svetozara Radića street, Savamala’s train system, and the BIGZ and Geozavod buildings. Additionally, one can see anachronistic technological inventions, post-dating the actual society, one of which is humanoid androids. Researcher Jelena Smiljanić calls this vision an “(…) onirist post-socialistic Belgrade, intermingled with Bodriarian (sic) simulacrums (…) creating a simulated hyper-reality” (Onirism was a surrealist literary movement in Romania during the 1960s, while in psychiatry it refers to a mental state in which visual hallucinations occur while fully awake). All of this taken together creates the retro-futuristic and surrealist setting of Bunker Palace Hôtel.

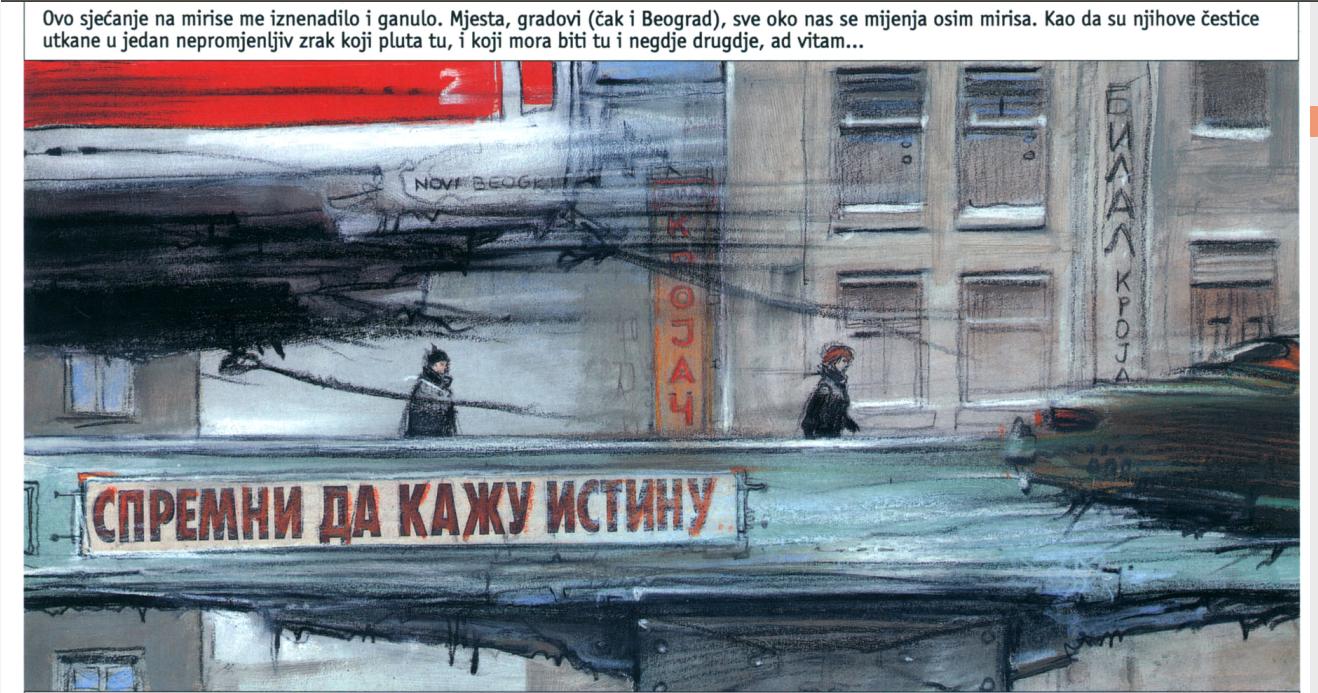

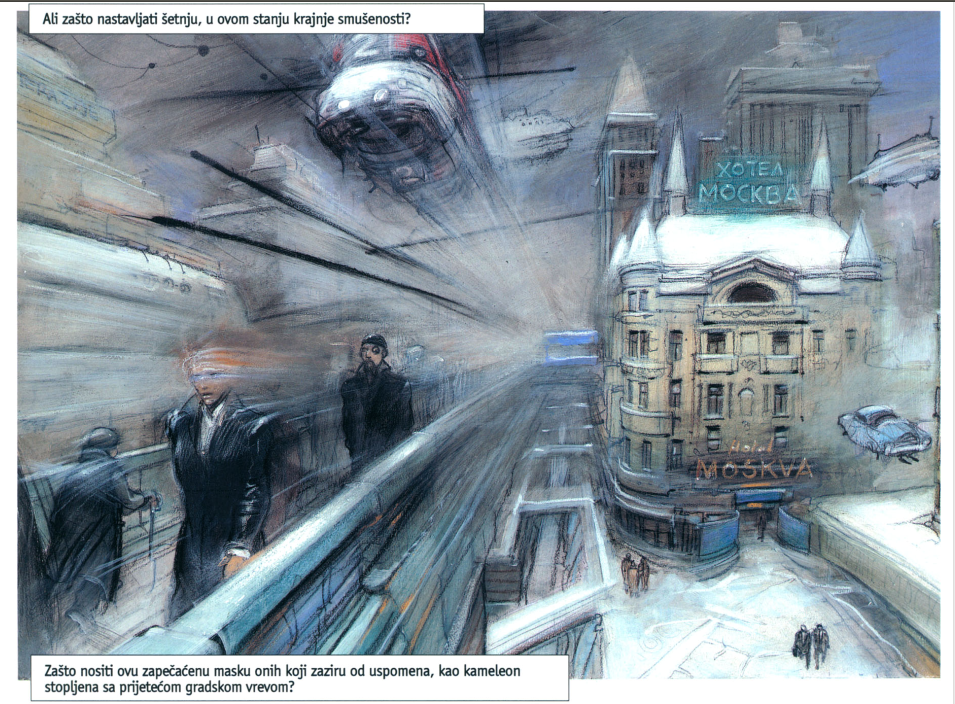

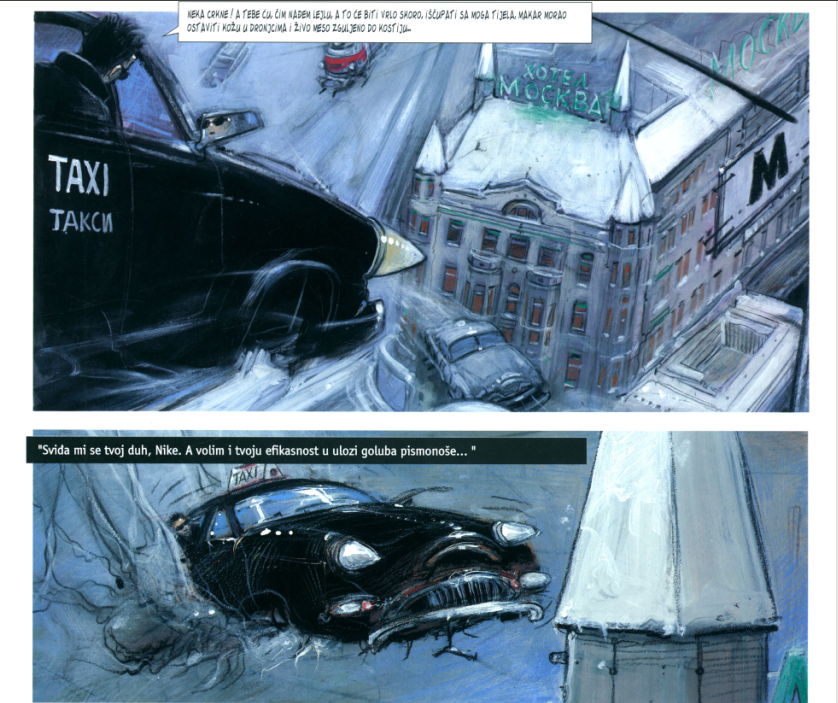

Different visions are present in Le Sommeil du monstre, or The Dormant Beast in English, also known as the Hatzfeld Tetralogy, which is one of Bilal’s latest comic series produced between 1998 and 2007. Set in 2026, it portrays what seems to now be a near future with advanced technologies in a dystopian, global setting. The narrative is revealed through two intertwined processes. Three main protagonists—Nike Hatzfeld, Leyla Mirković-Zohary and Amir Fazlagić, all orphans from the Yugoslav civil war—are trying to reunite with each other. The second narrative is Nike’s recollection of his childhood, taking us from the day of his birth in 1993 to the midst of the siege of Sarajevo. Bilal’s position shifts from one of the insider to a broader cosmopolitan global perspective; but it is his portrayal of the Balkans that I will primarily address here.

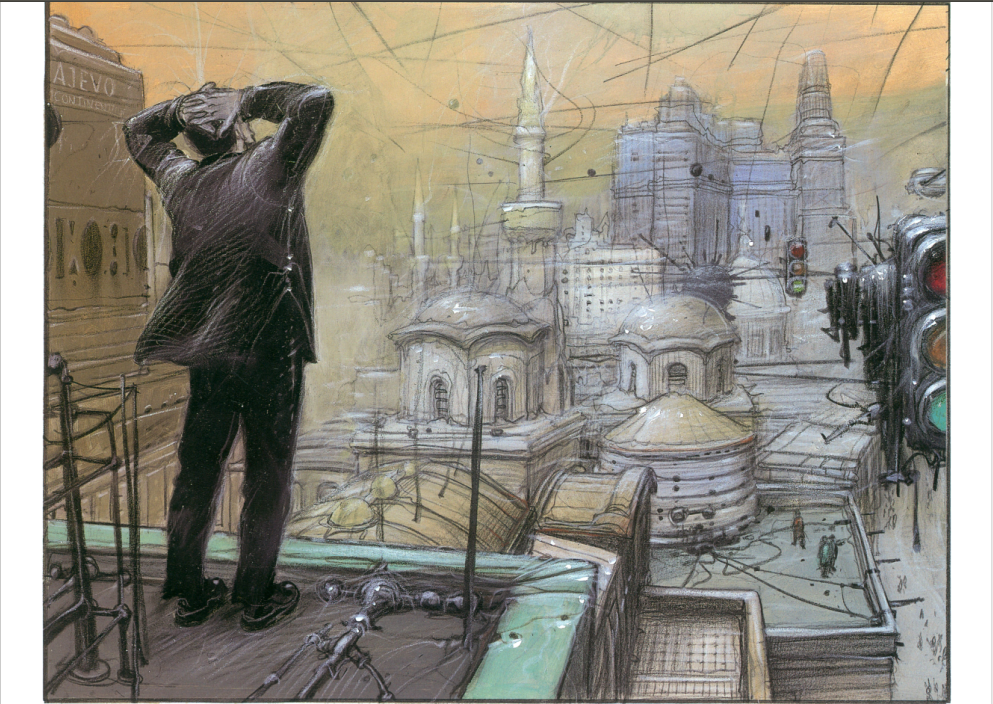

Belgrade and Sarajevo are two of the dystopian locations featured in Le Sommeil du monstre, presented (as in Bunker Palace Hôtel) in a retro-futurist mix where the old and the new are messily joined together. All cities in the series have a strong feeling of decay; as comic book author Zoran Penevski said related to Bilal, “it is the world of a narrative apocalypse.” In an interview for Serbian magazine Vreme, Bilal stated that Belgrade had changed little since when he moved to Paris in 1960. When he was asked in another interview why he avoided presenting contemporary times (war scenes in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina or the NATO bombing of Belgrade), he answered:

It is strange but when I’m portraying a brutal scene, I feel very uncomfortable placing it in the present. While if I position myself 20-30 years [into the future], then I can enjoy the creative process (…) I am visiting the future in order to come back to the past and the present. (emphasis added).

The narrative of a painful past and a not so optimistic future unwinds in the series, while the breakup of SFR Yugoslavia is still fresh.

The narrative of a painful past and a not so optimistic future unwinds in the series, while the breakup of SFR Yugoslavia is still fresh. Just after the Hatzfeld Tetralogy came out in 1998, Bilal said that his interest in Yugoslavia was triggered by the violent events of the war, the violence that triggered a “monster of remembrance”. The concept of reflective nostalgia coined by Svetlana Boym could be applied here, a nostalgia that does not tend to reconstruct the past but to instead be skeptical or critical of it, since the return to a imagined better past is impossible. In this case, it was the author’s creative way of purging the disturbances caused by the war.

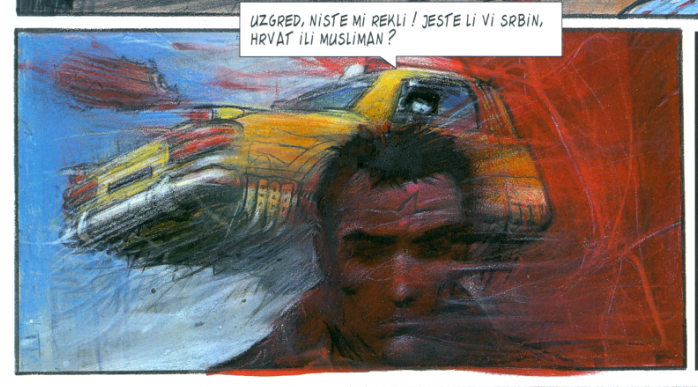

A dystopian mode is prevalent in the Hatzfeld Tetralogy, where the future brings a continuation of conflicts, but there are also some utopian sparks. Among those, Bilal also plants a powerful image of human segregation according to religious affiliation (and nationalism). According to an essay by Aurélie Huz and Irène Langlet, the avoidance of national or religious categorization of the main heroes (storytellers) in this comic pinpoints not only a state of uncertainty about identities after the dissolution of the joint state, but also Bilal’s own critique of segregation. If one accepts the argument that those very divisions contributed to the violent dissolution of multicultural life and shared space in SFR Yugoslavia, embedding similar divisions into a future society, for example in Paris (“Catholics only”, “Salafists only” in the comic), Bilal voices concern and a warning that history may repeat itself. This is why the question “Are you Serb, Croat or Muslim?”, posed several times, remains unanswered in the story.

The utopias of Aleksa Gajić

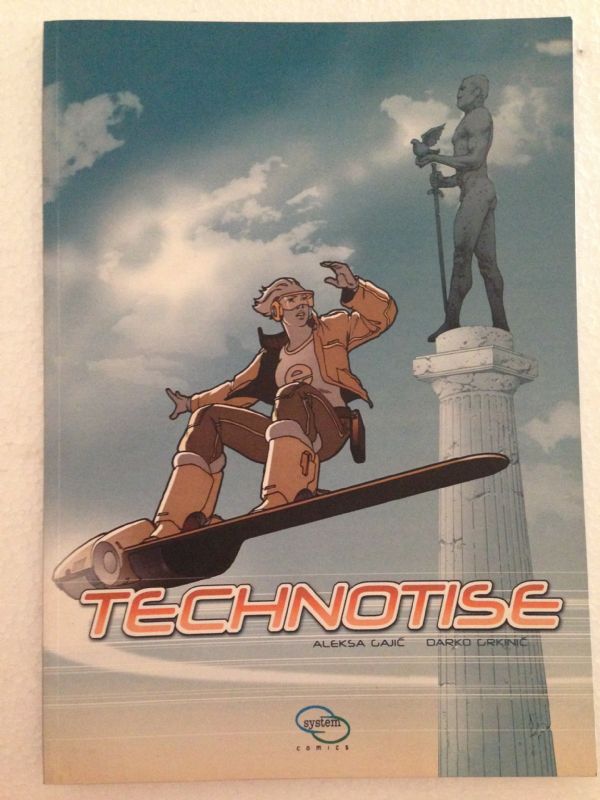

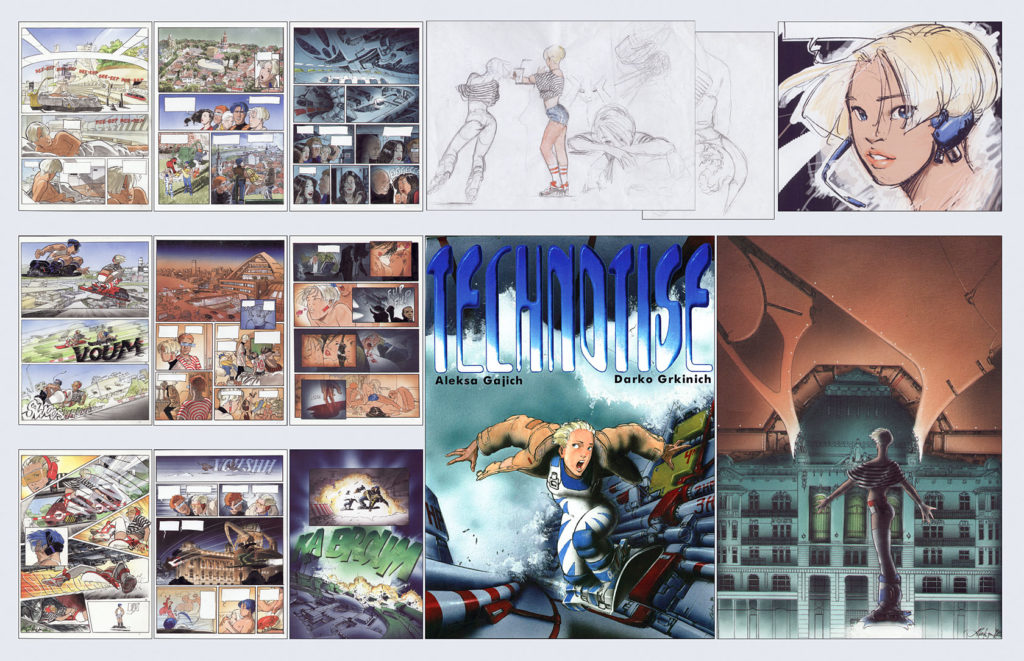

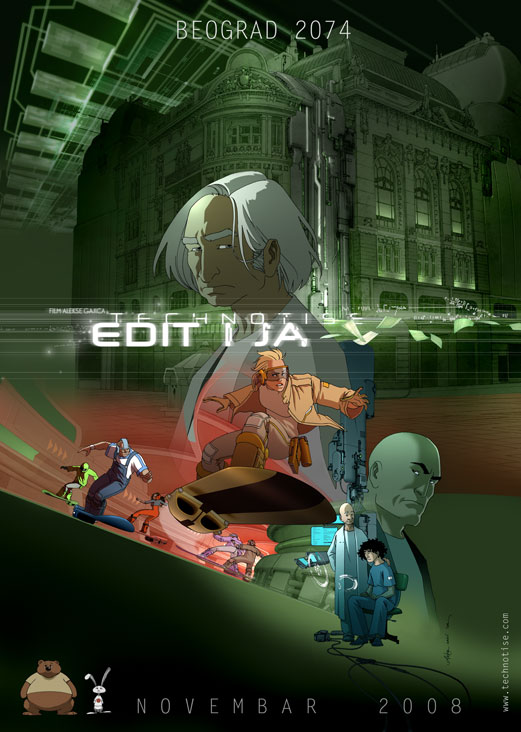

In contrast to Bilal, Gajić’s work has more humorous and light tones, a trademark of both his comics and animation work. He mostly works in the epic, fantasy, cyberpunk and SF genres, or something he calls “optimistična futuristika” (optimistic futuristic). These aspects of his work are discussed by Pavle Zelić and Anica Tucakov. Gajić’s bachelor degree project was a comic titled Technotise, with Darko Grkinić as a writer, and this later served as a starting point for Technotise: Edit & I (in Serbian: Tehnotajz: Edit i ja), which became known as the first Serbian feature-length animated film. In both works a utopian vision prevails, providing a predominant insider viewpoint of the portrayed societies.

The adolescents portrayed lead a hedonistic, middle-class life, centered around sex, drugs, hoverboard competitions and going out.

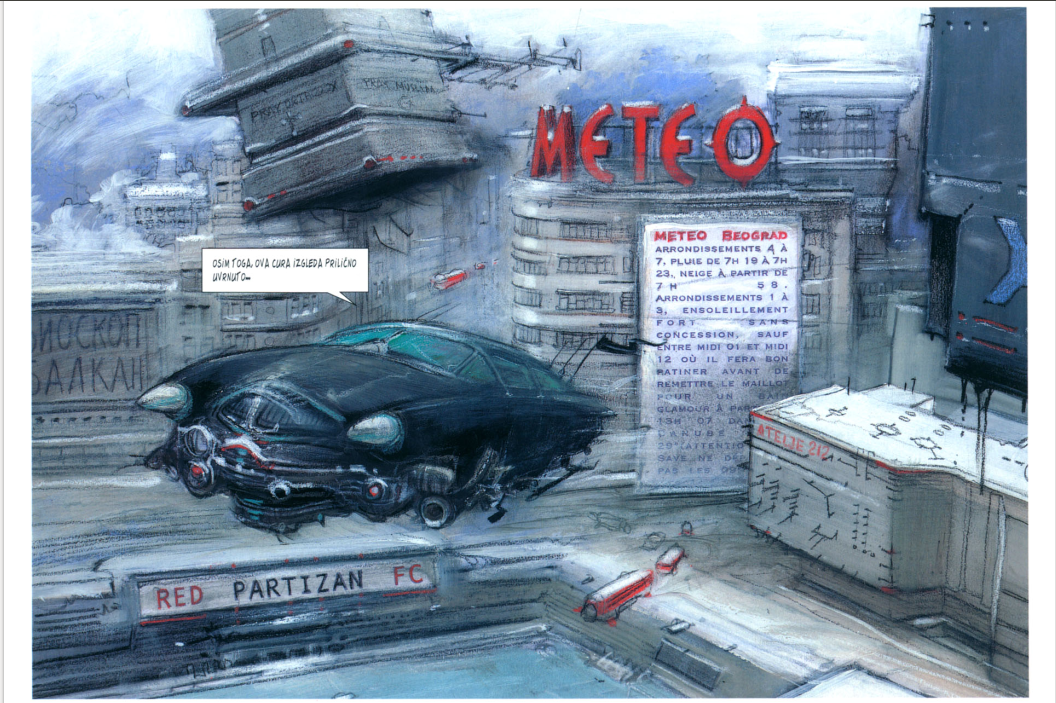

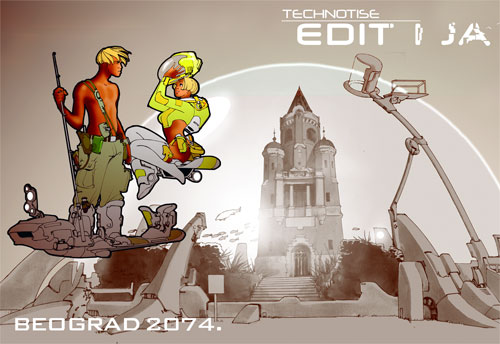

The Technotise comic (created in 1998, published in 2001) pays attention to two different time periods, both of which deviate from the present. At the very beginning there is a short episode from 1739, but most of the comic is set in 2074. It traces the adventures of a group of adolescents, led by Edit, in Belgrade. It is mostly set on the Great War Island (Veliko ratno ostrvo), a natural reserve between rivers Sava and Danube which are surrounding the city from two sides, and in Zemun, an old municipality where Gajić lives. The adolescents portrayed lead a hedonistic, middle-class life, centered around sex, drugs, hoverboard competitions and going out. Their names are a combination of foreign (Edit, Broni, Herb, Woo) and local (Sanja, Bojan), their looks and habits are seemingly typical of (western) teenagers but they are also contextualized through Serbian language, backgrounds and references. The film Technotise: Edit & I (2009) kept the main characters and semi-utopian quality with a more developed retro-futuristic, cyberpunk image of Belgrade. Real locations were shot and then futuristic details were added. In an interview (in Serbian) for B92 portal Gajić explains:

Belgrade 2074 is a city where the future came without an urban plan. Yes, the buses are floating above the streets, but also run late, so there are traffic jams. Facades are futuristic but also run down. The locations are altered, but still recognizable, so you cannot mix our capital with some other city. I made an effort to give this SF film a dose of plausibility, because I think that’s the way for the viewers to believe the story (…) That’s why the main hero is a regular girl with common problems that anybody can identify with and understand. At the same time, I haven’t given up my desires—I made a film I would like to see myself.

Recalling the different “gaze” positions I developed in the previous essay in this mini-series, the worldbuilding technique used in the film can be seen as an example of the present projecting itself directly into the future. A not-so-perfect setting reveals the social awareness of the film, pushed to another plane. Whilst it triggers humor, it can also remind viewers of the unresolved issues present in the Serbian and Belgrade society of 2009: Roma people collecting garbage in the city (here competing with robots), robots begging for new graphic cards, “eternal students” using tricks to pass exams (“bubice”), adolescents living with parents, telenovelas, old buses and police cars (Zastava 101 models), a rural grandfather yelling that children need to go back to the countryside and so on. Gajić draws attention to these references to the present in interviews by Sonja Ćirić and Ivana Matijević. Through its projection of present issues into the future, the film turns these present issues into a heritage that weighs down on the future and shows that the future does not automatically free itself from the problems of the present. However, optimistic tones are still prevalent, echoing a tendency in feature films of the New Belgrade School in post-2000 Serbian society, where authors are grasping the “(…) opportunity of this new start, constructing a virtual city made up of cultural and genre idioms”, as Nevena Daković shows in “Imagining Belgrade: The Cultural/Cinematic Identity of a City on European Fringes”.

Belgrade’s transformations triggered by the social upheavals of the 1990s and a feeling of a new start in the 2000s are most visible through film. Daković states that this cinematic cityscape is closely linked to space, time and matters of (transcultural) identity:

The cinematic cityscape is thus a complex identity performance. In the case of Belgrade, it presents a rich succession of identity conflicts and shifts, encompassing identities spanning from exotic Orientalism to virtual cosmopolitanism, with a nodal contrast articulated as Orient-rural-Balkan vs. Occident-urban-Europe. Belgrade’s city identity constantly vacillates between these poles, spilling over borders, moving between and among the times and spaces of the various identity constituents (emphasis added).

The cityscape changed from a socialist idyll, through the ghetto of the 1990s, to a “pure locus of the possible”—a cosmopolitan identity after the democratic elections in the 2000s.

In the context of post WWII Yugoslavia, and then Serbia, the cityscape changed from a socialist idyll, through the ghetto of the 1990s, to a “pure locus of the possible”—a cosmopolitan identity after the democratic elections in the 2000s. SF imaginings of Belgrade can therefore provide an understanding of contemporary positions and identities when the author’s projection is deeply grounded in the local context of Belgrade and Serbia, but also provide a means for temporary escape from the reader’s (or viewer’s) own body and society.

One of the major criticisms of Technotise in Serbia was that the film treated SF in a more humorous way, which was also a creative break with the majority of SF productions. Another critique was that it used youth slang and references to contemporary Serbian society. This situating of the film’s narrative, according to the author, was both a personal choice and a break from acknowledged patterns and habits of the genre, especially SF that is mostly set in highly developed technological societies in the West or Japan. A Serbian film critic, Dimitrije Vojnov, said in an interview that “in a (Serbian) cinematography so loaded with the past, the future rarely manages to reach the screen, and when it does, it is an ironic reflection of the present or past”, thus noting how Gajić diverged from a mainstream.

In preparation for his next film, Prophet 1.0 (Prorok 1.0), Gajić said that he wanted to present “the future in a Serbian, not American or Japanese, way.” And in explaining what is “Serbian” about Edit & I, he referred to the collaborators, financing, language, and topics. To this list, I would also add the Serbian locations. Curiously enough, this seemingly patriotic declaration does not include any loaded traditional or nationalist topics or statements within the artworks’ narratives. This mix between an international outlook and national (or local) grounding is connected to the affinity between SF and both “escapist” and critical situated knowledge, as I discussed in “Science fiction between utopia and critique.”

The identity of the (future) city—the identity of its ma(r)kers

These two dimensions of SF—the escapist and the critical—are present in the works of both Bilal and Gajić. Around two decades have passed between the UFOs that do not land in Lajkovac and the emergence of locally grounded SF in a Serbian context. In the cases of Bilal and Gajić, it is important to understand why they decided to contextualize their narratives in locations that they are physically and/or emotionally attached to. In both cases the topics were mostly a matter of personal preferences, which led to works that differ from the ones that the two artists do for the (mostly) French market. Bilal had already made a name for himself in the 1970s and 1980s, allowing him to treat contemporary, more politically engaged and personal topics with greater ease. But Gajić’s work for the French market differs from Technotise, which departs from and clashes with the market’s popular tropes, and this made him pause his international work during the film’s production. In facing many challenges while making the film, he said: “If the film doesn’t succeed, the repentant son will go back to France. After all, swords, magic, slaughter and the rest… it’s not so bad at all!” and “If I wanted money, I would have probably made a movie about little animals and wizards” (interviews with Peđa Popović and for Domino magazine, in Serbian).

Bilal and Gajić, in the narratives and messages of their artworks, have found ways to resist the official nationalist rhetoric that is so prominent in Serbian politics.

I would argue that both Bilal and Gajić, in the narratives and messages of their artworks, have found ways to resist the official nationalist rhetoric that is so prominent in Serbian politics. They are not, however, hiding their national identities in their work about Belgrade and the Balkans, into which they bring a strong sense of engagement and lack of concern for market pressure. The question then becomes: whose eyes are we looking through? What differentiates people from one another? The contextualization of stories takes place through specific characters, names, settings, cities, histories, and references, but at the same time avoids demonstrative national images, such as flags and other national symbols, religious affiliation of heroes and so on. In Bilal’s case, as already mentioned, characters refuse to identify with the causes of war, in protest, whilst Gajić finds politics overwhelming in Serbian society and prefers to find ways to create artworks that entertain and make people laugh. He views this as a more noble and honorable cause than being serious and scared.

Could this escapism embed in itself any Balkanism, as defined by Maria Todorova? In academia, the concept is defined as a discourse where the Balkans were (and sometimes still are) presented and constructed as the“other” of Europe, a negative stereotype, inverted mirror. In her book Imagining the Balkans, she states that creators of Balkan images from the Balkans itself are very self-conscious of the imposed discourse:

Unlike Western observers who, in constructing and replicating the Balkanist discourse, were (and are) little aware and even less interested in the thoughts and sensibilities of their objects, the Balkan architects of different self-images have been involved from the very outset in a complex and creative dynamic relationship with this discourse (…).

Another researcher, Maria Palacios Cruz states that “the Balkans seen from the Balkans” in film seem more concerned with being accepted than subverting the West’s images of the Balkans itself, thus reproducing criteria, stereotypes and divisions. Gajić’s escapism in the futuristic Technotise does not eliminate reality bites of SF Belgrade, nor does it avoid a sense of cosmopolitanism; after all, it provides a sort of hope. Bilal made a somewhat exotic Belgrade setting in Bunker Palace Hôtel, whilst in the comic series it is clear that the main characters are resisting nationalist narratives and paving an unstable road of their own, avoiding stereotypical media discourses. In Bilal’s own words:

I am not rejecting my own roots. When I say that it is dangerous to look inside oneself too much, in your own past, memories, remembrances, nation, religion, your territory, it is. That gaze is dangerous but I find it necessary. It is crucial to carry it with oneself and move with one’s own roots.

Conclusions: SF as cosmopolitanism?

Daković characterizes new film directors in post-2000 Serbia as employing escapism, cosmopolitanism and postmodernism. The cinematic cityscape of Belgrade is based on a “‘glocal’ identity [which] is made up of local elements with global appeal, local themes in a global expression and local events of inevitable global consequences”, quoting the definition by Paul Virilio. Or, as a beer ad in Serbia says: “global, but ours”.

Binarisms (local – global, national – international, patriot – cosmopolitan) come with a whole set of contextualized inclusions and exclusions. One’s attachment to a local stance might be seen as conforming to nationalism, even xenophobia, or as a resistance to the processes of globalization – or simply as staying faithful to the politics of location, as outlined by Donna Haraway in her theory of situated knowledge. Thus, one’s identification with a city might even be a means of resisting national identity (for more on this topic, see this study by Ivana Spasić in English). On the other side of an imagined pole stands cosmopolitanism, which is grounded in openness and universalism, criticized for being an elite stance associated with pro-Western and pro-European political ideologies in the Balkans.

In the Serbian context, after a global phase during socialist (or Tito’s) Yugoslavia, SF entered a (re-)traditionalist period grounded in nationalist political projects and imaginarium from the mid-1980s. This more traditional aspect of the genre contains many elements previously mentioned as characteristic of fantasy. Anthropologist Ivan Đorđević in his “Antropologija naučne fantastike: tradicija žanrovskoj književnosti” (Anthropology of Science Fiction: a Tradition in Genre Literature) says this production is in essence local, where certain traditional elements, taken selectively and strategically, create an image of how a culture sees itself at certain times (This perspective could be compared to Andrew Liptak’s article about nationalism in militaristic SF). Đorđević notes that a crucial distinction is made between Us and Them (Europe, the West, or the world in general), revealing the central gaze of traditional narratives as being nationally tailored. In this way, SF visions carry fears of losing one’s “roots”, or allowing cultural assimilation; that is, if the future is generally understood as cosmopolitan, with universal (most likely western) tendencies for humankind. This view of the imaginative role of SF echoes antiglobalization discourses.

The imagining of science-fiction Belgrade operates between tensions and opposites.

Overall, the imagining of science-fiction Belgrade operates between tensions and opposites. Just as in general SF, it provides universal knowledge claims about the future (and our global present), while at the same time situating the narratives in local history, social issues and geography. On a geopolitical level, it it susceptible both to Balkanism—accepting the Balkans as the “other” of Europe—and to Europeanism or Westernism—the construction of universalist global imaginaries. However, it is also a space for personal narratives and alternative visions, offering locally grounded stories, enriching the SF field. As such, it offers utopian and dystopian settings, escapism and social critique.

As Nevena Daković writes, “The transcultural identity and imaging of Belgrade is the result of a fusion of Balkanism and Europeanism, of local and global aspects in a city that is multi-layered and multi-faceted”. Which identity of the city will be used, in which setting and time (dystopian or utopian), heavily depends on the need to escape or construct alternatives in the present moment.

Illustrations:

- Technotise and Technotise: Edit & I courtesy of Aleksa Gajić.

- Bunker Palace Hôtel from Pinterest.com and WorldCinema.org.

- The Hatzfeld Tetralogy from TapaTalk.com, JogLikesComics.blogspot.com, Passion-Estampes.com, and Pinterest.com.

For more info on SF in Serbia (and Yugoslavia) available online:

- Project Rastko’s database on contemporary Serbian and South Slav fantasy literature (in Serbian).

- Ivan Đorđević’s “Anthropology of Science Fiction: a Tradition in Genre Literature” (in Serbian).

- Miodrag Milovanović’s “Brzi vodič – Science fiction” and “Srpska naučna fantastika” (in Serbian).

- Texts on SF by Zoran Živković (in Serbian and English).

APPENDIX

Belgrade Cooperative building—the center and mirror of city visions

Hey! (waving) Are you here for… HELLO! Are you guys here for the time travel tour?! Glad I found you so quickly, this place is crowded, follow me. Is it just you or are we expecting others to join us as well? Okay, good, we’ll have some extra space for us then, c’mon. Dobar dan – welcome to Experience Belgrade Through Time, the most popular time travel tour you can find in Serbia. As a promotional tour, we offer taking you to a selected point in the city and watch it how it changed during time. Once you book one of our full tours, you will be able to choose among other exciting programs going all the way back to the Roman times. Now please give me the vouchers, take a seat and put on the security bells. You learned a bit of Serbian already? Ah, rakija, of course. This tour will last for two hours and this time I’ll take you to a wonderful building you could find at Savamala district. Been there? Oh, it’s a must! Let’s go!

Stop 1: 1907

This is one of the city’s pearls, look at the beauty of it—decoration, monumentality, how it voluptuously imposes itself to the area, charming everyone. Let us have a glimpse inside… This building we usually call Geozavod, was actually made for the Belgrade Cooperative bank, by our famous architects Andra Stevanović and Nikola Nestorović, whose other works you could see in the area. It is one of the prime works of architecture in this period, mixing academic and Art Nouveau styles, Renaissance and Baroque decoration, and the first one using reinforced concrete in Serbia. Just move aside, izvinite… Saw these workers? The area was surrounded with new buildings, ponds and beaches, as one of the entry points where both merchandise and people arrived in Belgrade. Alas, after World War II, the cooperative bank was no more, the building had different and changing tenants, and underwent architectural changes. Luckily, it was never bombed! Speaking of bombs, let us go the our next stop

Stop 2: 1989

Čoveče, do you recognize this one? How could it be? The building really underwent a bit of a deterioration, like the whole Savamala district, becoming a place filled with old glory, noise, shady characters and almost forgotten. Or simply unpopular to hang out to. But this one is actually from a surreal movie by a French artist born in Belgrade, do you know who he is? I’ll give you a tip, he made comics… Nikopol? Immortel? (beep beep) What’s this? Nevermind, the movie Bunker Palace Hotel took place in an alternative reality, at the very end of socialism of Yugoslavia, Belgrade being its capital. In the movie, it’s a hotel, but actually a bunker for members of a ruling regime, hiding from a mysterious threat… I won’t tell you more, please do see the movie, and if you like film history, check out Kinoteka’s tours as well!

Stop 3: 2012

Look at the old lady, all run down, but still standing proudly. Nostalgic gem, memory of times passed, but not too long so nobody would remember its past glory. Ah, the building was used for rave and techno parties from the 1990s, imagine that – marble and electronic music, glass paintings and stroboscope. Somewhere from late 2000s, artists started coming to the area, making it present and interesting for Belgraders again. Do you hear the music? That’s one of the festivals, happening just behind the corner, do you see all the young people? Is the area coming back to life? I remember those times when I was young, thankfully nowadays we could live longer to testify about it. We were a bit afraid back then, afraid of the specter of gentrification, an army of yellow machines tearing down the area we we trying so much to nurture… Let us not interfere here, we need to follow the laws of time travel—stay unspotted, do not change anything.

Stop 4: 2016

After years of being neglected, finally rise and shine! In 2014 the building underwent a major redevelopment as part of Belgrade Waterfront project, which has its seat there. What do you think, do you like the neglected charm or new life? During these years the area started changing drastically—many buildings were torn down and streets disappeared, while others, like Belgrade Cooperative gain a new chance, as part of the investment plan. These skyscrapers behind it are blocking the view towards the river, and many inhabitants found it very controversial—who would live here, when gentrification made it so expensive for all the local people? We… who? Security guard? Oh, do not pay much attention to that guy at the corner, there’s always a busybody at the corner… but we may still go further up the street a bit.

(beep beep) Why is this beeping again? Sranje, look at that mass of people, full trust upward… Huh, I’m sorry, I haven’t paid attention to what lies ahead. It seems I took us right in the middle of the protest against Belgrade Waterfront! These people are supporters of Don’t Drown Belgrade initiative. Yes, we’re safe on this altitude. And this was not a violent protest. You can find some data about it in the hand-outs. And that big yellow duck over there – that’s their symbol! “Duck” in Serbian could mean a joke, a scam. Let us move away from here, I can hear the helicopters approaching, and I need some space to maneuver to the next station.

Stop 5: 2074

Huh, peaceful again. Watch out for the tram. You see, we’re in animated setting! Another artist, comic book author Aleksa Gajić, made a vision of Belgrade which is both old and new, with old-fashion, socialist trams, early 20th century architecture and futurist inventions. The trains are levitating, Belgrade Cooperative has a virtual reality dome, and the Belgrade looks… what do you think, familiar, nostalgic? Nicer than it really is? This was made in 2009, it is interesting to see how people back then imagined our times. (beep beep beep beep) Ok, this is it, the promo tour is ending, I wish to have spend more time with you, for that please do check our full tours, we’ll be able to travel for a whole day, there’s so much to tell about this city… If you have a half of minute of your time, check out the evaluation form and rate me as your guide… thank you, you too, vidimo se neki drugi put!

I would like to thank professor Nevena Daković at the University of Arts in Belgrade for her help in writing the original paper, Charlotte E. Whelan for proofreading and Rut Elliot Blomqvist for excellent editing.

Srđan Tunić is an art historian, freelance curator and cultural manager based in Belgrade, Serbia. A fan of science fiction, this is his first text about it. Contact: srdjan.tunic[at]gmail.com

This piece is part of Not afraid of the ruins, our series of science fiction and utopian imaginings.

To receive our next article by mailing list, subscribe here.