by Sasha Plotnikova

This August, large parts of the Amazon rainforest were set on fire to make way for the exploitation of land for industrial agriculture, causing the loss of over 1300 square miles this year alone.

It should come as no surprise that the destruction of the world’s most vital source of oxygen was incensed in part by the same private equity firm that has waged a global war on the human right to housing. What links these disasters is the fact that our political economy has redefined land as resource and therefore as potential capital: homes become real estate, the forests that replenish the earth’s atmosphere are seen as obstacles to agriculture.

The myopia of this kind of thinking easily infiltrates the design fields, which have largely adopted a pro-market logic over the past century. Architecture and urban design specifically have suffered from lack of interdisciplinarity in practice and navel-gazing in their academic culture, resulting in an approach to today’s ecological and social justice crises that is overwhelmingly hands-off, or milquetoast at best.

A new, new world

The project of imagining what the future looks like is as old as the practice of architecture. Architects are futurists by necessity: we occupy ourselves with projections of the shape of things to come. Often, these ideas surpass what’s possible in the present and live their lives on paper, never finding concrete expression in the real world. This so-called “paper architecture” makes up a stunning amount of what’s been canonized in architecture history books. But whether paper architecture can make a difference in the world outside academia hinges on its ability to challenge the preconditions for architecture. By identifying present shortfalls in our political, economic, social, and ecological systems and projecting the form of possible alternatives, speculative design can imbue the discipline with political agency.

In StudioTEKA’s 2100: A Dystopian Utopia: The City After Climate Change, a Brooklyn-based architecture studio dives deep into a question the building industries have neglected to ask: how much longer can the world’s cities withstand the rapidly increasing frequency of disastrous climate events? And what happens when they no longer can? The writers estimate that 83% of the Amazon would be destroyed by 2100; today’s toll already brings that percentage to a tipping point of 15-17%. 80 years too soon, we realize that the issues addressed in this book are all the more pressing.

It’s a fascinating thought experiment: can we pack up and reassemble this lifestyle in newly temperate climates? StudioTEKA seems to think so, given the proper technocracy.

2100 depicts a world in decay, and sheds light on what a possible post-decay world might look like. StudioTEKA’s proposal stems from the expectation that our politicians will do little, if anything at all, to bridle the destruction of the biosphere over the next 30 years.

It’s a fascinating thought experiment: can we continue to consume resources at our current rate, and be able to pack up and reassemble this lifestyle in newly temperate climates? Will we be able to go back to business as usual after the climate collapse plays out over the next century? StudioTEKA seems to think so, given the proper technocracy.

The master plan in 2100 looks like this: if we can force politicians to take action by 2050, we’ll be able to limit warming temperatures to a 6-7 degree rise by the year 2100. By most measures, even a 3-4 degree rise would be monumental. The Earth’s middle band, which hosts most of the world’s population in 2019, will largely become uninhabitable due to drought, severe storms, rising sea levels, and catastrophic heatwaves. StudioTEKA predicts that 10 billion people will then move to inhabit 39 million square kilometers of newly-developed compact megacities near the Earth’s poles.

To allow for this density, each megacity outsources its energy production and manufacturing to a sister “extraction city” in the middle band. There, renewable energy is harvested, natural resources are processed and both are exported to the corresponding megacity. The plants are staffed by temporary workers that travel to the middle band from the poles. The designers refer to these projections as the “new, new world.”

The servant and the served

Expanding on the architectural trope of the servant and the served, StudioTEKA suggests seven such pairings around the world, with densities 2.5 times that of present-day Manila, today’s densest city. Using methods of visual representation that are customary to architects, the predictions and solutions in 2100 convincingly spin a linear narrative out of the chaos that we’re about to see unfold in real time. Through compelling infographics, the authors script a future characterized by a harmonic relationship between humans and ecology, as a foil to our current pattern of reckless exploitation.

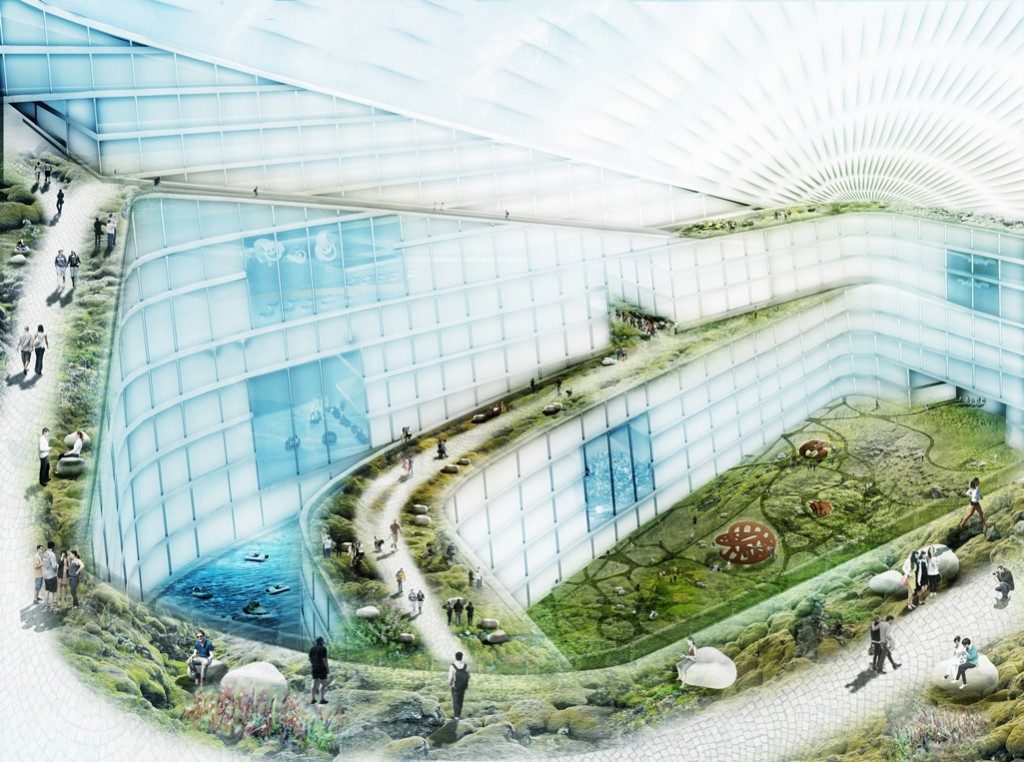

In 2100’s Antarctica, three quarters of Ross Island are maintained as a nature reserve. Agriculture and recreation are housed in crystalline greenhouses on stilts, and artificial glaciers are farmed for water. This water is exported to Ross Island’s sister city Johannesburg and to other cities with water shortages. A rendering of Troll, Antarctica shows a neighbourhood-sized concrete dome housing a mossy sculpture park ringed by a river designed for indoor boating. During the dark polar winters, Troll’s residents travel to Sao Paolo to aid in mass reforestation efforts, sleeping in pods suspended above the urban forest’s understory.

With the historic fabric of Manila projected to be underwater by 2100, the city is rebuilt on a linear plinth elevated above the water. The plinth is designed to harvest of storm energy, which is then loaded into large batteries and exported to Wellington. Wellington’s coast is also flooded, and the communities are moved up to a new megacity distributed amongst the mountaintops and linked by bridges.

As frequent hurricanes render New York uninhabitable, Greenland’s largest city, Nuuk, rises as the capital of global finance. In Nuuk, buildings bury themselves into cliffsides; and in New York the historic fabric is rehabilitated to house the temporary workers that come to work in carbon capture and energy-storage export.

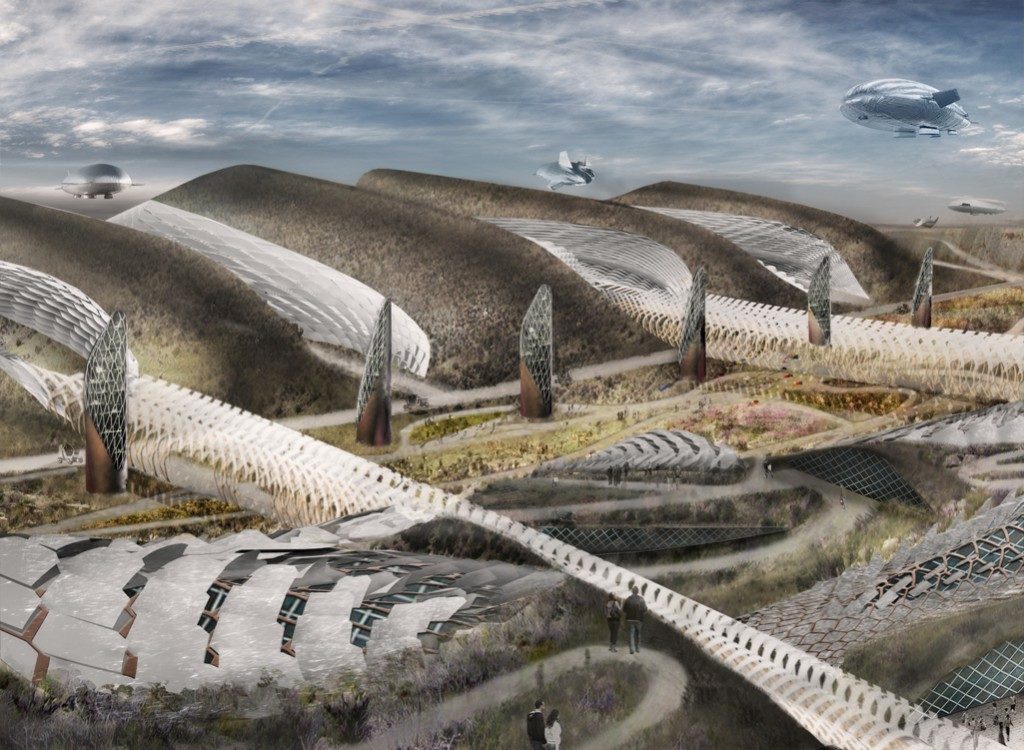

A megastructure weaves through Moscow, stitching together the public space on the ground level with transit and bikeways up above, significantly densifying the city while maintaining open space on the ground level. Its partner city is found in the hostile desert landscapes of Kufra-Adjabiya, where extensive water evaporation infrastructure creates humid zones for agriculture and human habitation.

A top-down approach

StudioTEKA’s approach to designing this new, new world stems from a mix of utilitarianism and a biomorphic design sensibility. Every design move is based on how many functions it can make the architecture perform: building facades can no longer merely separate inside and outside and give buildings a face—they now also grow plants, harvest energy, and capture carbon. Parks not only provide recreation space, but act as carbon sinks, perform soil remediation, and provide a barrier against oceanic storm surges. Like the different organisms that make up an ecosystem, each element of the built world plays a muti-faceted and active role in its environment.

There is no discussion of who will be left behind as millionaires buy up the hot new real estate of the compact megacities; no hint of universal rent control and no plan for the construction of public housing.

Uniting the fourteen sites is a single aesthetic language of twisting, white sinewy forms with parametrically-designed perforations that form megastructures, towers, or domes scaled much larger than the majority of the architecture we’re familiar with today. This design language has its roots in biomimicry—a desire for human-made forms to look like, or even imitate those of nature. Think of Santiago Calatrava’s World Trade Center Oculus in New York, or Studio Gang’s Aqua Tower in Chicago for built examples of this tendency. The unintended consequence is that the forms proposed in 2100 could not look more unnatural in the historic city fabrics and cultures that they colonize.

Zooming out to the urban plan, we see a top-down approach: in some cases, a new figure is superimposed over an existing street grid, while a series of clip-on developments colonize a historic city fabric in others. The architectural proposals are deliberately gestural and unresolved, acting as placeholders for the kinds of forms that this design ethic could produce. What’s missing is a clue towards the kind of society these places are meant to foster, and the political economy that we would need in order to get there without leaving anyone behind.

Everything is the same, but on acid

Interestingly, 2100 was written during the last years of the Obama presidency and before the proposal of the Green New Deal (GND)— a model for “greening” the US economy that’s being pushed by leftist Democrats. Similarly to what’s depicted in 2100, the GND proposes a shift to renewable energy and the creation of “green” jobs. The dominant narrative amongst its proponents has paradoxically broadcast the GND as a growth-driven vision of a sustainable future. At their worst, both the GND and the world of 2100 enact a kind of common sense on acid; a sensibility held in common in a world dominated by capitalistic thinking. Already, Left critiques of the GND have articulated a GND that challenges the economic framework at the root of the climate crisis. Meanwhile, 2100 suggests that the right cocktail of new technologies, scientific research, and continued economic growth might allow us to keep living just the way we do.

What neither 2100 nor the GND address is the scale of production and natural resource extraction that would be required for a transition to renewable energy at this magnitude. Renewable energy has far-reaching material implications that will require the growth of mining operations across the globe.

The scale of construction proposed in 2100, too, has massive material implications. Given that real estate development is one of the world’s most most carbon-intensive industries, the proposed undertakings speak to our desperation in the midst of the climate catastrophe. In 2100, finding habitable environments takes on more urgency than reconfiguring the scale at which we extract, produce, import, and consume. As a chapter title poignantly asks, “Where in the world can we live?”

Futurism with class bias

The research that informs StudioTEKA’s specific design solutions, technologies, and site selections is remarkable for a design studio. But honing in on the technical makes the political the book’s weak point.

While they note abnormalities in the effects of climate change (like the escalator effect, which will lower sea levels at poles while raising them around the middle band) and even suggest ways to address renewable energy’s intermittency problems (the gaps in energy supply that follow lulls in weather events); StudioTEKA never address what many fear to be an approaching climate apartheid—the poorest left behind in uninhabitable places while the rich flee to new eco-utopian enclaves.

2100 is a world in which we have our cake and eat it too: where we can continue to grow the economy while lowering our energy use. How the current class war plays out in this dystopian utopia seems to be a question these designers won’t approach.

It’s crucial for designers to recognize the ways in which both the climate crisis and—ironically—“green” building solutions most negatively impact working class communities and the developing world. By largely limiting their research to scientific reports and big-picture population data, the designers have missed a huge opportunity. And so, the book reveals its class biases as it rolls out a long, intricately curated and site-specific list of technological and lifestyle-based solutions.

For example, 2100 hypothesizes that a unanimous shift to plant-based diets will occur, reducing the amount of land needed for farming by 36%. This kind of thinking ignores the integral role that sustainable, small-scale animal husbandry and meat consumption play in countless cultures in North America and around the world. It misses the mark. Instead of shifting the blame onto the individual, we must hold the Big Agriculture giants to account for their recklessness towards the environment. While the rate of meat consumption among non-Indigenous populations in the US and Canada poses a number of ethical issues, as well as public health and environmental concerns; so does a sudden, massive shift towards diets that depend on soy and nuts for protein. The industrial production of these plants depends on monocropping, which is already eroding away our biodiversity. The blind spot occurs again and again throughout 2100. It doesn’t attempt a critique of the market-based approaches to urban design that catapulted us into this crisis in the first place. There is no discussion of who will be left behind as millionaires buy up the hot new real estate of the compact megacities; no hint of universal rent control and no plan for the construction of public housing. The authors don’t acknowledge that the extraction cities will depend on a subjugated class of migrant labourers, while the bourgeoisie and the professional managerial class will be able to remain in the relative safety of the compact megacities year-round.

Essentially, what’s proposed is a world of advanced capitalism and 100% renewable energy. Drawing on research by Ecofys, a renewable energy advocacy firm, the ideas in 2100 hinge on the idea that ”energy use can be lower while living standards and economic development continue to rise.” For the most part, 2100 is a world in which we have our cake and eat it too: where we can continue to grow the economy while lowering our energy use. How the current class war plays out in this dystopian utopia seems to be a question these designers won’t approach.

A world without a middle scale

The world we’re shown is one that architectural renderings have become very good at depicting: brand-new, glassy, hyperbolic building forms tower over outsized green lawns and criss-crossing pathways populated by a parade of stock humans. There’s a lack of a middle scale in these proposals, which was also a major failure of Brasilia or of the contemporary dystopia of Kazakhstan’s capital, Nur-Sultan. While it’s easy to copy and paste stock images of people milling about in an urban plaza; it’s much harder for a designer to create true community spaces. Much of what’s shown is a world of heavy-handed designs that impose a unified aesthetic across an entire landscape, ignoring the patchwork of vernacular buildings that characterizes the organic growth of our towns and cities.

In her introduction to the book, StudioTEKA principal Vanessa Keith suggests that the solution will be both bottom-up and top-down, quoting from Bossomaier and Green’s Patterns in the Sand, “…We have to focus on the local interactions: change these, and the rest will follow.”

But where are these “local interactions” in 2100? Rather than offer a “trickle-up” ideology such as that of radical municipalism, the designs within the book offer a vision of top-down design and of a large-scale, global model of production.

Saskia Sassen’s buoyant introduction speaks to the idea of “delegating back to the biosphere.” She sees cities, in all their complexity, as our best impression of the biosphere itself and applauds the book’s authors for moving “beyond mitigation and adaptation.” Reading between the lines, her words seem to beg for a new definition of what it means to be urban, not for an evolution of the techno-metropolises we already have. A sweeping shift to renewable energy means employing the biosphere in our systems of production rather than empowering the biosphere. The book ultimately maintains a dualism of human and land, in which land continues to be seen as a resource.

The notion of urban growth is identified as a challenge in the foreword, but goes unquestioned for most of the book. Many of the designs echo the wistful refrains of architecture academia – more schools, more libraries – because spaces for community are inherently more engaging to design. But to be able to work on these kinds of projects, designers need to tackle the overhaul of the political economy head-on. We need to work with other disciplines to imagine and implement a culture of mutual aid needed to prioritize these institutions.

Design for a world after capitalism

It’s fitting that this ambitious project was taken on by an architecture studio. On the first day of school, architects are told that we will change the world. We’re told we are generalists; that our work is the work of many disciplines, synthesized into its material form. But as real estate and resource extraction continues to drive our social and environmental ecologies into collapse, it would be a mistake to think we can simply design our way out in the traditional sense. What we need are interdisciplinary approaches at the scale of what StudioTEKA has begun to do, but with a much more headstrong focus on reshaping our political economy—a conversation largely ignored in design circles. The sites in 2100 are chosen strategically, and they suggest a monumental mass migration but never once mention the ugly ways that the class system of capitalist nations rears its head in a “green” transition.

The flaw of 2100 is not that it’s unrealistic—in fact, it follows the protocols of today’s neoliberal environmentalism quite realistically to their natural end. But it does not offer us a way out.

There is one proposal in the book that does stand out as a more sophisticated challenge to architecture’s habit of producing more stuff, and as a provocative step toward a new kind of city. In the Phoenix scenario, StudioTEKA propose a “green deconstruction” of a city that, in 2019, is the heart of the the fastest-growing metropolitan region in the US. In the plan, the region plummets into severe drought and experiences a mass exodus. It’s then transformed into one of the proposed extraction cities as its housing stock is hand-demolished in phases with the goal of salvaging building parts and making way for dew collectors, greenhouses, solar farms, and wind parks. This scheme implies a massive overhaul of the real estate market through the expropriation of homes to the city. In a beautiful display of what architect Keller Easterling has termed “subtraction,” a city is imagined to shrink to a scale that might allow for a more localized economy, and possibly for much stronger solidarity between its residents, largely seasonal renters who work in the city’s proposed renewable energy sector in the mild winter months.

The flaw of 2100 is not that it’s unrealistic—in fact, it follows the protocols of today’s neoliberal environmentalism quite realistically to their natural end. But it does not offer us a way out from a system that privileges the few at the cost of the many. On the whole, the proposals in the book are bold, but prove to be flimsy as they reveal their failure to take into account that the climate catastrophe arises from the ecology we have created for ourselves—a system of being in and understanding the world in which a capitalist political economy sets the terms.

We need to ask: how will ecosystems withstand the increased mining of rare minerals needed for the capture of renewable energy? How will we organize a growing population in a way that is sustainable, while maintaining a connection to the land?

We need to ensure that our innovations aren’t funneled into building “climate-proof” fortresses for the rich. We need to demand that frontline communities are prioritized; that real estate speculation is abolished; that with a reconstruction on this scale we can also overhaul our political economy into one that ensures what Donna Haraway calls the “ongoingness” of all. Designing for a post-climate crisis world inheres designing for a world after capitalism.

All images by StudioTEKA.

2100: A Dystopian Utopia: The City After Climate Change by StudioTEKA is published by UR (Urban Research) and is available for $48.

Sasha Plotnikova is a designer, writer, and activist living in Los Angeles. She is a proud member of the Los Angeles Tenants Union, the environmentalist study group OOLA, and the architecture faculty at Cal Poly Pomona. She tweets at @sashaplot_.