by Shaina Agbayani

(1) land

“Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.”

-Malcolm X, 1963

When I was in Luzon this past year, burning sambong allowed me to connect & celebrate the two sacred lands that have given me life. Sambong is a philippine plant medicine, a cousin of Turtle Island sage.

*Turtle island is the name given by several Indigenous cultures to what Europeans have called “North America” since colonization.

Burning sambong became a ritual that reminded me of my braided creation story, raised by a Turtle Island aunt and Philippine mother that have both given me life. Amongst many other medicinal plant beings that connect Turtle Island to the Philippines, partly as a result of Spanish colonial trade relations, are tobacco and corn, both of which hold their places in the stories of my elders’ childhoods.

The more i reflect on my relationship to these two lands, the more i come to relate to Turtle Island as an aunt who was forced to take me in under conditions of violence & force, and yet still has loved and given so much life to me, and the Philippines as the mother whose many children have left her because colonial pillage has fragmented, objectified, and violated her in ways that make it hard for her take care of many of us.

After spending committed time in solitude with mother earth in my ancestral lands for several months this past year, I came back to Turtle Island with a deeper sense of reverence for this Aunt who has taken so much care of me and enabled my life under conditions of settler colonial violence.

(2) life

I keep returning to the question of how i can integrate practices of love and care into my everyday survival in a way that will allow me to go beyond surviving to regenerating my self, ancestors and an-sisters, cultures, and the communities and lands that allow us to be. For me this has meant that prayer, song, connecting with plant and element friends, dance, and other body connection practices form intentional rituals in my life. They have become forms of regenerative medicine, my body being the land that cultivates and carries them regardless of where i am in the world. More broadly, i ask myself how communities and lands impacted by deep colonial harm can not only survive but regenerate in the context of systemic subjugation, extraction, and violence.

At this year’s annual March for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, I noticed the powerful smell of burning sage and the use of other sacred medicines. This, as well as the presence of song and dance, brought spiritual, emotional, physiological healing to the march while reviving Indigenous ceremonial practices. It reminded me of how incorporating traditional practices of care and creativity—specifically when these practices are led by people from the communities they are indigenous to—can transform the often sanitized, colonized, cold spaces of marches. I often wonder how spaces of mourning and loss can be transformed into spaces of cultural revitalization. The singing, dancing, and burning of plant allies at the march felt like forms of cultural resurgence as people viscerally connected to their creation stories through medicine and their bodies.

At the march, Ellen Gabriel spoke of how we cannot wait for the state and the law to protect and honor Indigenous womxn. She also stated that the protection and celebration of Indigenous womxn’s lives requires a cultural shift whose embodiment the law cannot ensure. In this way, she speaks to how politics based on gaining visibility and recognition under the legalistic terms of the nation-state is limited in its capacity for revitalizing indigeneity, healing inter-generational trauma, and ensuring the regeneration and celebration of Indigenous womxn’s lives.

In the same vein in the paper “Anger, resentment and love: fuelling resurgent struggle“, Leanne Simpson asks us to reflect on this connection between the violence against Indigenous peoples, the land, and the politics of recognition under the state .

“I am a bigger threat to the Canadian state and its plans to build pipelines across my body, clear cut my forests, contaminant my lakes with toxic cottages and chemicals and make my body a site of continual sexualized violence. What if we collectively and fully reject the politics of recognition in politics with the Canadian state? What if we collectively and fully reject the politics of recognition in our mobilizations and organizing? What happens when we fully reject the politics of recognition in education? Where do I beg the colonizer for recognition in my own life? Why?”

(3) body

“Our backs tell stories no books have the spine to carry”

-rupee kaur, poetess and spoken word performer. From the poem “Women of color”

While in the Philippines, I felt on the deepest level the truth that our bodies are the land. The silent time of solitude i took to be on the sacred Mt Banahaw and in other spaces of unconcretized, respected earth were truly the most powerful and transformative times of connection to my body & ancestors.

As a queer femme filipinx performer, provider of emotional labour and care work, and as daughter, niece, cousin of many filipinx people who have worked dedicatedly as care & domestic workers, I’ve experienced how my body and other racialized feminized bodies become sites of consumption, fetishization, and energy extraction through, for example, underpaid, unpaid, and industry-specific labour that tends to be domesticated or sexualized.

As a performer and as someone who is often asked to do emotional labour in specific ways, I’ve experienced how the values and stereotypes ascribed to my brown feminized body as a site from which to extract energy connects to the way that colonial-capitalist institutions relate to the body of our mother earth as a site for resource extraction through, for example, mining and fracking.

And so I feel what many Indigenous womxn visionaries like Leanne Simpson and Amanda Lickers of Reclaim Turtle Island have expressed in different ways—that asserting the bodily self-determination and sovereignty of womxn and queer folks, especially those most impacted by colonialism, is intricately linked to asserting the self-determination and sovereignty of the land. As such, both womxn’s bodies and the earth are sacred sites through which communities, cultures and institutions can be made to reproduce colonial values. Womxn play a distinct role as culture-bearers, and the cultures we bear reflect and are enabled by the lands we inhabit.

(4) remembering womxn and land through song and dance

The babaylan in Filipino Indigenous traditions is a person, usually a womxn, who, according to Leny Strobel, director of the Center for Babaylan Studies, “is gifted to heal the spirit and the body; the one who serves the community through her role as a folk therapist, wisdom-keeper and philosopher; the one who provides stability to the community’s social structure; the one who can access the spirit realms and other states of consciousness and traffic easily in and out of these worlds; the one who has vast knowledge of healing therapies.” As noted by Grace Nono in “Songs of the Babaylan”, many babaylans integrate song and dance as part of their healing, spirit, and land connection practices.

The babaylan were seen as a threat to colonial powers because of their strong connection to traditional cultural practices, their dedicated and intimate relationship to the land, to spirit worlds and to plant and medicine allies, and their commitment to preserving all these land-based connections. Christianization and colonization involved the regulation and removal of Indigenous community connections to the land and suppression of philippine Indigenous spiritualities. As part of this, babaylan traditions were forcefully regulated, and babaylan were demonized as witches or brujas and subjugated—forcing many to go into hiding or minimize their visibility.

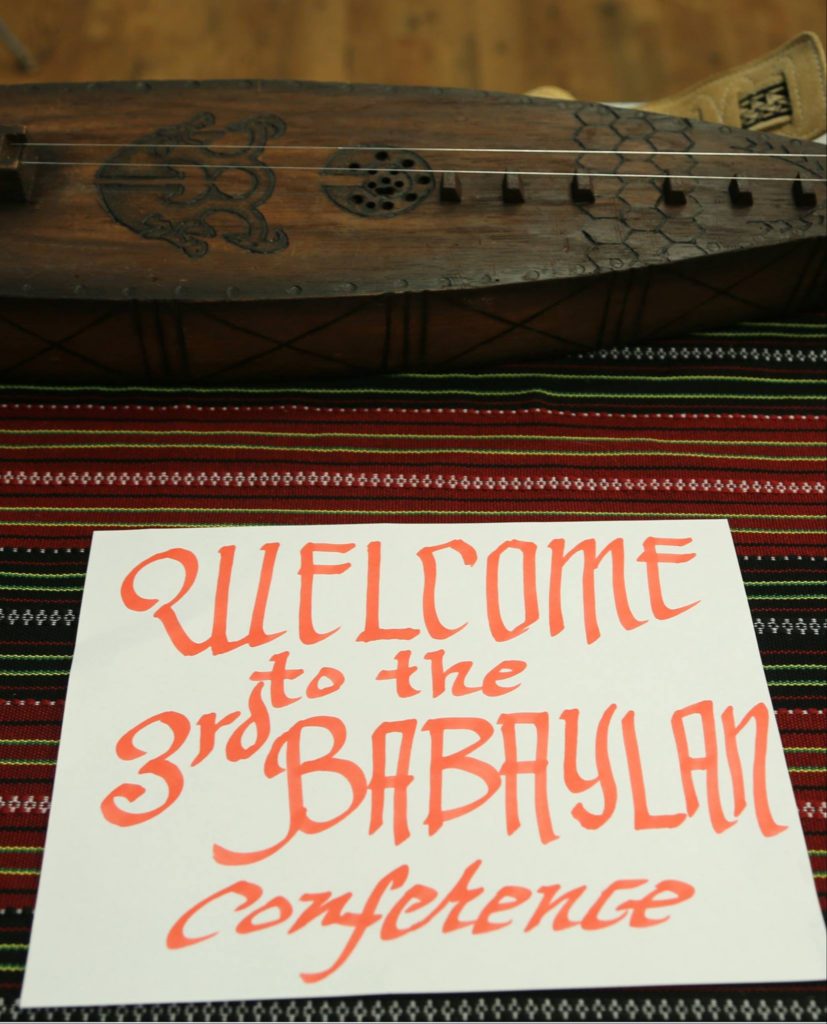

In September, I was present at the Babaylan Conference, themed Makasaysayang Pagtatagpo (Historic Encounters): Filipinos and Indigenous Turtle Islanders Revitalizing Ancestral Traditions Together. It was hosted in Coast Salish Territories—an unceded territory within what settlers call British Columbia. The conference has been happening in Turtle Island since 2013 and strives to “build and strengthen our Filipino communities in the diaspora through the sharing of Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices (IKSP)”. This year’s theme focused on questions of how to meaningfully connect with Philippine Indigenous knowledge systems and spiritualities in a way that engages with the realities of our presence on Turtle Island.

During the conference, I co-guided “Queer Earth”, a session by and for queer participants. A central intention for me was to invite reflections on the role of song & of queer folks (and queer song!) in movements of re-indigenization. Specifically, I wanted to reflect on (1) how we might re-connect to our intuitive, embodied ancestral knowledge to return energies to mother earth through ritual and specifically song and (2) how my relationship to being queer is deeply rooted in a relationship with the earth which embraces fluidity, diversity, connection, negotiation, and reciprocity not just in relation to gender and sexuality, but in my relations to all beings, and (3) how these two might intersect.

What ended up organically emerging was a collective grieving of our queer ancestors—from our unknown queer ancestors, to our queer aunts and uncles within our blood and chosen family—which was marked by spontaneous song, lots of crying, prayer, and oral reflections of what brought us to the room. While communally mourning the lives of those passed, we also collectively and musically affirmed our queer selves, and held one another’s queer stories and the emotions and hopes that sprung from them. In the session I felt a release of grief through my own mourning, a release that seemed to be collective as I witnessed others’ mourning, and shared reflections with participants about the session afterward. One of the co-facilitators, Will, mentioned this was the first markedly queer congregation at the conference since its inception, which left me feeling like this process of queer mourning of lives passed was also inherently a process of queer resurgence.

For me, the organic emergence of song with the percussions we made out of our bones and tongues deeply reverberated through and revitalized my emotional, physiological, spirit self. I felt the truth held by many Philippine Indigenous knowledge systems that storytelling through song is a way of connecting to and enabling the survival, return, and celebration of our an-sisters. As Grace Nono notes, in many babaylan Indigenous traditions, song helps to connect to the spirit world in a way that can and does bring back our an-sisters and ancestors, revitalizing our connection to our selves, the earth, our ancestors, and cultures.

At the conference, I also reflected on the role of dance in revitalization while witnessing the collaboration between two dance groups. Butterflies in Spirit is “a dance troupe made up of mostly family members of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women that raises awareness of violence against Indigenous womxn and girls across Canada. BIS commemorates the victims of violence in Vancouver and across Canada”. During and prior to the conference, Butterflies in Spirit collaborated with the Kathara Philippine Indigenous Dance Collective in a fusion of contemporary hiphop with traditional dance choreographed by PowWow dancer Madelaine McCallum and with live musical accompaniment by Kathara.

The dances at the conference re-created many stories of rebirth and renewal through depicting the metamorphosis of butterflies, the migratory flight of birds, difficult journeys through sacred waters, and the welcoming of nations after long journeys. Dance can be a form of community practice that celebrates cultural life through remembering creation stories in movement, nurturing communal bonding, and affirming relationships with spirits & the land through connection with the body and with emotions. The embodied stories I witnessed reminded me that amidst all the dispossession and violence against brown bodies and lands, communal practices of re-connection with body, culture, and land are well alive.

The collaboration reminded me of what Leny Strobel, director of the Center for Babaylan Studies, said during the conference that “we are not people separated by land, but people connected by water.” I viscerally felt this as I witnessing the dance against the backdrop of the Sunshine Coast’s waters, which summoned my inner waters to well up through my eyes as I watched. I left the conference being reminded of the regenerative role that song and dance can play in our movements for healing and justice.

(6) (in)visibility and (ir)recognition beyond the nation-state

“While theoretically, we have debated whether Audre Lourde’s “the master’s tools can dismantle the master’s house”, I…I am not so concerned with how we dismantle the master’s house, that is, which sets of theories we use to critique colonialism; but I am very concerned with how we “re” build our own house, our own houses. I have spent enough time taking down the master’s house, and now i want most of my energy to go into visioning and building our new house” -Leanne Simpson, Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back

“The inner resources of the people that cannot simply be reduced to resistance. This – cultural energy – is also power – but it is a power not meant to dominate nor resist but creatively for a people to become themselves.”

-Albert Alejo, Generating Energies in Mount Apo

In my experience within the social justice communities of Tio’tia:ke—the Kanien’keha or Mohawk word for Montreal which means “where the currents meet”—creative & spiritual practices such as our song & mourning circle in the conference—are less valued forms of activism than more visible, outward, street-based, masculinist, and legally-oriented forms. Activism is often based on making certain peoples, identities, communities, movements, and goals visible and legitimate within a legal, nation-state framework that measures value through positivist, hyper-visible, masculinist, standards. This often looks like demanding for “rights” on the streets and in the courts, on the terms of the nation-state’s legal and political frameworks.

I am forced to adopt these frameworks of being recognized by and visible to nation states for purposes of mobility whenever I travel across the border and am asked for my passport which upholds my “Canadian” nation-state settler-colonial status, and when I apply for my passport and must choose one of the two genders recognized by this nation-state. The nation-state’s visibility and recognition are part of my existence. Its laws and institutions impact my existence even if i would like to opt out of and become invisible from them.

In some ways, I value making visible the invisibilized, for example in remembering those who have been made missing and murdered by the settler colonial nation state, and in making visible the invisibilized, un(der)paid emotional, spiritual, labour of the black, brown, Indigenous, racialized bodies on which the nation-state depends. I cannot refute that visibility does matter when nation-states regulate many of our lives, and that visibility can be an important way for people to, for example, survive through accessing resources that the nation-state is a gatekeeper of.

Yet we need to remember that these are by and large resources these institutions, and their agents, have violently extracted from the labour, lands, and communities of those from whom they gatekeep these resources. And as as I move toward a place of imagining how to commit to regeneration (of the lands, waters, self, culture, ancestry, and communities that give me life) beyond survival, it becomes undeniable to me that nation-state legal frameworks are based on upholding and glorifying the state as a place to merely ensure the bare survival of racialized people, especially Black and Indigenous womxn. The movements to grant the earth and queer people recognition and protection under the law, such as the global movements toward legalizing and decriminalizing queerness and the “granting” of “people status” to lands and rivers are done in an unequal, western, human-centered power relations where the state at the end of the day gets to set the terms of who is granted protection from state violence itself.

The nation states of Turtle Island have been built on systemic violence against racialized, specifically Black and Indigenous, peoples through impoverishment, dispossession, disappearances, killings, mass incarcerations through the prison industrial complex, resource extraction, and food apartheid that sickens and poisons—slowly and fastly kills—communities. And the more that these realities of this nation-state violence are revealed to me, the more clear it becomes that the legal framework of rights and recognition through which it operates is invested in the bare minimum of survival for Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.

So the question this begs for me is: do I actually want visibility from the nation-state, or is it precisely invisibility that I want? Of course, the answer to this is very contextual. Nonetheless, I feel strongly that the choice of invisibility and un-recognition from the nation-state as forms of surviving and thriving is invaluable in our recognition and rights centered political/social/spiritual landscape.

Invisibility from the state can enable the conditions for survival, sovereignty, and self-determination, and therefore resurgence and revitalization. During the Japanese occupation of her village in World War 2, my grandmother was given a medallion from her grandfather to make her and her home invisible from Japanese soldiers. Her home was the only one not burnt down in her village. She’s here, I’m here (and queer!), and we’re hella regenerating, fueled by our love for one another and our communities. It is precisely in invisibility from the state that many off-grid Indigenous, Black and Brown communities are co-creating for themselves the conditions to thrive and regenerate beyond the conditions of regulated survival on which the nation-state is built.

(7) regenerative medicine: love & creation stories

“You can keep your political purity. I choose love.”

-Lindsay Nixon, an anishinaabe-nehiyaw writer, curator, community organizer, and researcher currently residing in Tio’tia:ke/Mooniyang (Montreal), Facebook post. May 23rd.

Normative political activism for me has too often been devoid of the loving—nurturing, caring, sustaining, (re)creative—energies that make the process of working toward justice feel loving, just, life-giving, regenerative, sustainable.

Activism that celebrates what has been made invaluable and invisible—from all the emotional, cooking, cleaning, & care work that sustains us to the spirit world with whom we co-exist—not only complements legalization efforts to recognize and protect, but is necessary if we want to go beyond survival and de-colonization to regeneration and re-indigenization. I want to commit to an activism that celebrates our connection to all the invisibilized lineages, labour, histories, her-stories that transmit to us and enable our (re)creation stories of past, present, and future.

Of course, there is no one linear, one-size-fits-all way to survive and thrive under all circumstances for all peoples. A diversity of tactics makes sense for the unique, dynamic, fluid, ever-changing times and spaces that call for the heterogeneous “us” to survive and thrive. I am not here to tell people to stop petitioning nation-state governments when the state has a real, violent, impact on our lives. Rather, I am affirming the value of acknowledging and challenging the systems of harm that often prevent us from surviving, and inviting us to reflect on how we can co-create conditions to sustain and regenerate ourselves through harnessing love within our communities independent from the nation-state. This is a call to transmute the (very valid) rage against destructive systems that harm us into energy that allows us to regenerate and sustain one another through nurturing love for ourselves. This regenerative self-love requires knowing, remembering, and re-creating ourselves.

Perhaps through taking the time to mourn and remember those who have enabled us to be here, by breathing, by offering our sisters food and feeding ourselves, or offering our ancestors food on our altars. Perhaps this knowing comes through story-telling, perhaps through song, perhaps through dance.

#waterislife, we cannot dance without water

Support #noDAPL

Two Spirit Warriors & Water Protectors Camp

Shaina Agbayani is a queer femme broom-wielder butterfly-singer, film-maker, dancer, cook, fermentation-fairy, cleaner, and co-creator of beat:root and re:bodies. She resides between different parts of luzon and tio’tia:ke in kanien’kehá:k, haudeonsaunee lands. She keeps offerings at https://queererth.wordpress.com

To receive our next article by email, click here.