All that is left to us, therefore, is to understand what the disaster is producing within us, to pay attention to the explosion of affects it reveals. Therein lie the complexity of the situation and its rare promises. –Sabu Kohso

by Shrese

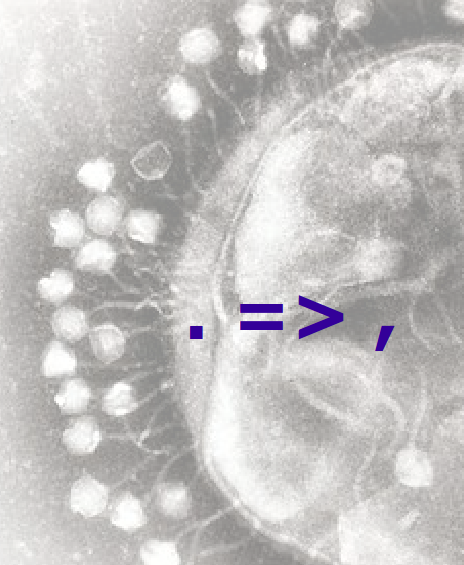

Stories of viruses are mostly stories of surface breaking, membrane crossing, confinement evading, border shattering, punctuation changing.

During the 19th century, scientists like Pasteur and others articulated the Germ theory: diseases could be passed on by tiny living things (hence the name microbes, small biota) invisible to the eye. Bacteria, organisms made of a unique cell, were “discovered”. An object, the Pasteur-Chamberland filter, was created to filter out bacteria from water. First dedicated to research, it also became an industrial device in a world now, and forever, scared of microbes and infections. But still, stuff that seemed to be smaller than bacteria, i.e., that could pass through these filters, kept on causing diseases. “Filterable viruses”, later only “viruses” (from poison in Latin), became then known to humans.

Viruses came to our world by crossing a membrane of unglazed, or bisque, porcelain. Here their narration starts—as if they hadn’t been there all along. Kevin Buckland, a storyteller living in Barcelona, teaches us this about the virus: “[its] power is simple: it can change periods into commas. It can un-end sentences. What was sealed and solved, what was packaged and piled, what had already been swept away is now again unfinished; ready to be rewritten.”

These past weeks, our days have been filled with digressions about viruses. For example: are viruses alive? Yes, no, it depends on how you define “alive”… And it depends on who you ask: someone living through the Covid-19 pandemic, or the same person a couple months ago?

This question has been with us for as long as viruses came into our world. After they first crossed over the Pasteur-Chamberland filter, they were thought to be liquid entities. Then they became particulate. But what were they really, were they just toxins? Were they microbes? Nowadays, we talk of them as being at the edge of life, we ascribe them the gift of life only once they have crossed our cell membranes… The debate often follows a script:

—Viruses cannot self-generate their own body nor self-reproduce, therefore they are not alive.

—Don’t they, though?

—Well, yes, but they are not independent nor autonomous, they cannot do it on their own, they need to infect a cell to do it.

—But some organisms also need other organism-hosts to reproduce. —Ah?

—And how about you? would you be so independent and autonomous if you were in a world without any other living beings?

—…

Indeed, asking “is this alive?” forces us to think “what does it mean for something to be said to be alive?”. Another way to go at it is to come up with lists of criteria, checklists, so we can tick “yes” or “no” when it comes to viruses, and the debate is still not closed. All in all, this is a tale of defining a phenomenon “en creux”, that is by focusing on what is excluded by the definition. This debate of finding the limits of the domain of life does sound abstract, but it is quite a spectacular contribution by the virus.

If you ask “what does a virus do?”, any biologist would tell you: first, it attaches itself to some elements on the surface of the cells of animals or plants (bacteria have their own made up category of viruses called bacteriophages). Then, using a diversity of tactics, it will pierce through the surface membrane of the cell. Once inside the cell, the pathogenic type of viruses will generally hack what the cell does for a living (grow and reproduce) to reproduce itself to a vast amount. After some multiplication, the virus will often engage with borders again, this time to actually literally explode the membrane of the cell, rupturing all structural integrity, spreading its inside outside. The cell, at this stage, can safely be considered “dead”. See, it’s all about trespassing surfaces.

This is the official story. But there is some more unfinished business to it. We mostly think of viruses as pathogens that infect us, make us ill, kill us. They are defined and perceived solely from their function or from their way of life (a bit of DNA or RNA genome encapsulated that needs to infect a host to actually do anything). Does it make sense to lump all of them together under this single term? Their genomes can be of all kinds and shapes, their structures as well, also their rules of engagement with the cells. But above all, it seems that one important activity of theirs is to mix things up: they insert their genomes into their hosts, they pick up bits as well, they move these bits from one organism to the next, they may have got stuck into cells to make new kind of cells. We’re now in the world of Lynn Margulis and her symbiogenesis stories—evolution as unfinished digestion: biological entities attaching to or entering into other entities and sticking around. The most famous example is the organelles found inside cells, like the mitochondria or the chloroplasts, coming from bacteria that were “eaten” by other bacteria and stayed there. Some say that the first eukaryotic cell (a cell with a well-defined DNA nucleus) came from an actual virus entering a cell.

We should have listened to Lynn Margulis more. For one, she did offer a solution to the “what is life?” dilemma: life is not a thing, it’s a process. Indeed, what does an organism do? It grows. What for? To grow more. And Darwin was all well and good, but she insists the metaphor of the tree was terrible. Life is not made of independent branches of organisms, lineages that go their own paths separated from others. A more suitable metaphor would be the web: all these “lineages” bump into each other, cross each other, don’t respect the borders—neither the ones of the organisms, nor the ones of the taxonomists.

Taxonomy. This is another story of containment and packaging that got shattered. Taxonomy is the science of classification: ordering things into distinct categories, according to specific criteria. Essentially, compartmentalising, detaching, separating, confining… Taxonomists as border guards. Here, Debra Benita Shaw and her account of “promising monsters” is very telling. When she teaches us that “monsters are the necessary counterpart of taxonomy, [they] emerge both within the strata of the taxon and across its boundaries” and that “species are trapped in a taxonomic grid, but they are always struggling to escape/mutate”, it is almost like she’s telling us stories about viruses. Her monsters are both essential to the production of categories, taxonomies and hierarchies and to their undermining and challenge—they are mobilised to produce what is accepted as normal but they linger on, they proliferate. They are abnormalities that refuse to disappear, nagging us every now and then like a stone in a shoe; but they also are “unexpected formations that contain latent potential”, the deviations that hold the possibilities of future changes, evolutions and apparitions of new forms (such as the concepts of saltation and hopeful monsters in evolutionary biology).

It is easy to think of what is destructive about viruses, especially on Wednesday 1st of April at 21:04 in Barcelona, Spain. We are drowned in curves of new Covid-19 cases (is it flat yet?), sunny and tempting empty streets from our balconies, graphs of daily deaths, migrant persons fined for being out in the streets helping out others… And it is particularly telling that the answer to a virus, given its ability to plough through our established categories, was to multiply the confinements: lock downs, movement restrictions, imposed distancing and isolations, borders closing, modes of transport shut down. But what could be promising about all this? True, at the moment, there is no shortage of interesting propositions and analyses telling us that the coronavirus is an opportunity for social change, an indicator of the failure of capitalism, a tipping point from which we won’t turn back, a planet saviour, nature biting back… Funnily enough, one interesting contribution was proposed by the virus itself, in a monologue. The virus even managed to strip down the situation to the core bifurcation it offers us: “the economy or life?”. Here it is again, forcing us to think about life.

Writing from within the pandemic, and a very specific vantage point (pretty privileged: work from home, cheap rent, no family responsibilities, official European identity papers—borders again), days are of a new kind. Constantly in the background, coming and going, tensing my jaw, aching my shoulders, piercing my chest and shortening my breath, an “aaaaaaaaaaaaaaahaaaaaaa!”—anxiety, fears and worries.

Not so differently to a couple of centuries ago, viruses are invisible to most of us. They travel in droplets, in aerosol, linger on surfaces, clothes… anyone contaminated and in their incubation period, not showing any symptoms, could potentially pass it on. Not even some indirect clue of the risk. So much hand washing. Our relation with our hands has changed completely, they are the vectors of the invisible threat. Our mouths, our eyes, our noses are the points of entry. Scared of our own bodies, we embody the neo-liberal conception of life described by Silvia Federici “where market dominance turns against not only group solidarity but solidarity within ourselves”. In this situation, we are in constant state of fear of what’s within, “we internalize the most profound experience of self-alienation, as we confront not only a great beast that does not obey our orders, but a host of micro-enemies that are planted right into our own body, ready to attack us at any moment. […] we do not taste good to ourselves.”

The invisible does not only carry the feared entities. This is also where capitalism relegates its waste: air, ocean, underground, “ex”-colonies… All tales told, viruses seem to fit the risk society pretty well. This is the idea that our contemporary society has shifted to an obsession with safety and the notion of risk, and has dramatically shaped its organisation in response to these risks. From a class society where the motto was “I’m hungry”, and where social struggles were organised around this, the risk society’s motto became “I’m afraid”. This created a different set of demands, mostly revolving around the need to feel safe. The risks are mostly invisible (as in, actively unseen: nuclear, chemical toxins, oil spills, terrorism etc.). What therefore becomes central is to decide what constitutes a risk. Because scientists are now the ones that are relied on to make this assessment, science became a particular battlefield. In this framework, risks are divided into external and manufactured risks. The former are “natural” risks that arise from the outside (drought, floods, earthquakes—what “nature” does to us) and the latter occur because of what humans do to “nature” through its techno-scientific practices. Rob Wallace begs us to keep in mind that plagues are manufactured risks. The multiplication of zoonoses (infectious diseases that spread from non-human animals to humans), he argues, is a direct result of the capitalist modes of production: intensive monocultures, reduction of diversity, destruction of habitats… To quote the virus again, the “vast desert for the monoculture of the Same and the More” that we created is responsible for this pandemic.

What could exemplify more these invisible manufactured risks than the nuclear complex and its associated irradiations? And how this reminds us of viruses. They are both hyperobjects, a term put forward by philosopher Timothy Morton to describe phenomena that imply things, temporalities and spatial scales that are beyond humans while intimately present—disproportionate, monumental and apocalyptic while mediated by minute invisible entities. Also, responding to these disasters is difficult. The true apocalyptic nature of these events is not that they will bring the end of the world, it’s precisely that they are never ending, one characteristic of the societies of control. Nuclear waste and viruses will of course survive countless generations of humans. The monumentality of this kind of catastrophe seems to call for a monumental solution, initiated by a superior power, discouraging all revolts. But above all, it is the virtual reality of radioactivity and viruses that throws us off. Impalpable, invisible, delayed effect… nuclides and viruses diffuse in our world and bodies through uncontrollable and unreliable movements. As hyperobjects, they are viscous: “they ’stick’ to beings that are involved with them”. In a nuclear explosion or a pandemic, we cannot stop our bodies from welcoming the radiations or the virus. They engage with our cells—manipulate, use, modify, hamper them and threaten their integrity. Suddenly, reminding us that we are made of cells, our own body integrity is at stake, and potentially the ones of our offspring, or our closest ones…

No wonder a lot of my fellow humans are lamenting “these days, I cannot think”. Cannot focus. Head in cotton, like when taken by the fear of heights. But it is known, this is not fear, it is a desire for heights. From my balcony on the 6th floor, peering over, I am both terrified and excited. Powerful craving to let go, to give in to the air and gravity. Fly, even for a few fractions; fall, finally free of the fear, warmly wrapped in the friction of the resisting atmosphere—a liberating suicide.

We are now petrified by the phenomenal amplitude of the situation. Confined, we are utterly confused when faced with the satisfaction of one of our deepest and most repressed cravings: stop. Take a breath and shut down the machine. Stand still, there, wrapped in all the muck that we did not want to be with, reminding us of the many ways we kept busy to avoid facing ourselves. Finally giving in to the temptation—that has never left us since the first day of school—to stay in bed, retreat, desert and abandon.

As Sabu Kohso reminds us when writing about the Fukushima disaster, we will not save the world. Our starting point could be to disassemble the totality that was sold to us as The World, relocate its membranes and change its punctuation, to recompose it offensively with new terrestrial relations that are already solutions to live the good life. “In this mix of affects—despair, joy, anger—that a lot of us share, we are tempering, quenching and forging new weapons, and we are elaborating strange tools and curious talismans, to lead ephemeral and intense lives on this earth.”

All images by Shrese.

Shrese is a carpenter and independent researcher based in Barcelona, Spain. Contact him at shrese at riseup dot net.

This article has now been republished in French by lundi.am.