Source: Red Pepper

by Aaron Vansintjan

We proposed a broad vision of how to create a new world in the shell of the old in the last three installments of our column. We can chart a new path forward by grounding that vision in the lessons learned from past struggles and an understanding of how hierarchy is the shared root of oppression.

But this can all feel a bit intangible without clear examples. To get an idea of what we want the future to look like, we need to take inspiration from and learn from those already building the institutions of tomorrow, today. In the next few installments, we’ll be highlighting movements and initiatives that we think are some of the seeds of a new world, already sprouting.

In the summer of 2015, the streets of Barcelona pulsed with a victorious energy. Members of the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH), a grassroots organisation fighting to stop evictions in the wake of the 2008 housing crisis, had started what they call a ‘citizen platform’, Barcelona En Comú.

Popular movement

Though they were registered as a political ‘party’, all decisions would be approved by citizen assemblies and participatory processes.

A year later, they won the majority of votes in the municipal elections on a platform of participatory democracy, defending social justice and community rights, and reversing a neoliberal city government model.

Some old photos of Ada Colau, a prominent PAH activist, being handcuffed by the police in an occupation quickly circulated. Incredibly, she was now Barcelona’s new mayor.

Ada Colau was asked if she was surprised by their victory in an interview with Democracy Now!’s Amy Goodman. Her response spoke volumes:

“It was a victory that was accomplished in a very short amount of time. It was a candidacy that was supported and driven by the people. With very few resources and with very little money, we achieved victory in the elections of such an important city as Barcelona. But partly it was not surprising, because there’s a strong popular movement and a strong desire for change.”

Transforming the city

For those living in Barcelona in 2015, it was obvious what Ada Colau meant. Winning City Hall seemed like a flexing of the muscles, an afterthought for a social movement so dynamic and alive that victory seemed almost inevitable.

The new way of doing politics was already prefigured in the streets: people intuitively knew what kind of city government they wanted, because they lived politics in the day-to-day at their neighborhood assembly, at the anarchist social centres, and in their self-run community gardens. It was only a matter of time before these new politics would enter City Hall.

Four years down the line, and Barcelona seems a different city. Self-organised neighbourhood assemblies send representatives to discuss and suggest new policies. Each policy is then put up for approval in an open online vote before it is brought to City Hall.

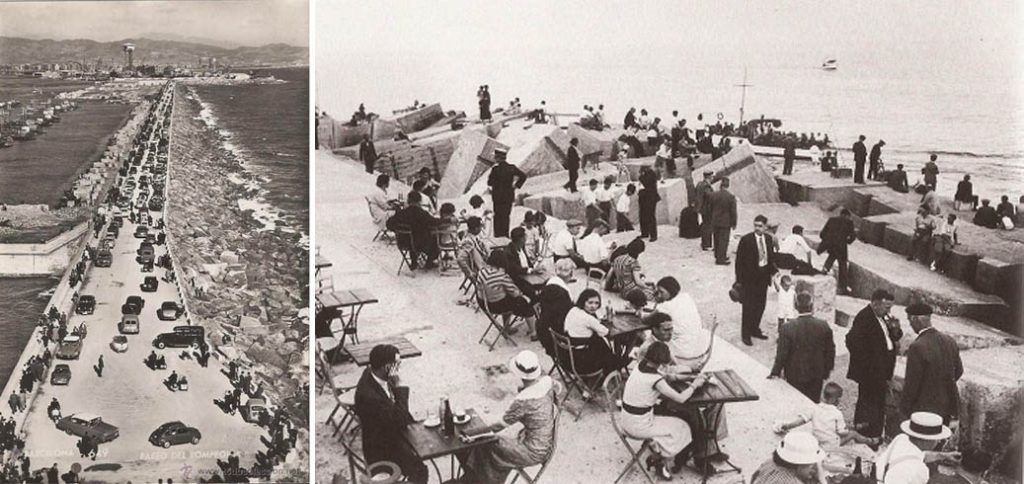

The brand new ‘citizen platform’ has carried out a well-publicised battle against AirBnB, changing the laws on short-term rentals and trying to minimise the impacts of tourism on residents’ lives.

Now they want to take control over the privatised water company, and build ‘super blocks’ that turn multiple blocks of the city into car-free areas.

Municipalist movements

But during the same time period, the Catalan independence movement cleaved society in two. The new municipalist party found itself in the center of the conflict: it was accused of either not outright supporting the independence movement, or of not doing enough to stop it.

This is a common problem faced by many social movements in modern liberal democracies. As radical urban movements grow, they become more and more integrated into people’s daily lives—providing basic needs, educating people, transforming public space into a site of politics.

But at a certain point, they have to choose to either directly confront, or enter, the government. And as soon as they do get elected, they are forced to deal with the contradictions and predicaments of liberal democracy: constitutions, political alliances, and nationalisms.

To get an inside look of what it’s like to be part of a social movement that has taken political power, Aaron Vansintjan interviewed Kate Shea Baird, an activist now working for Barcelona En Comú, spending much of her time on the international committee, Barcelona En Comú Global.

There, Kate works together with other municipalist movements globally, providing resources and organising public events, like the Fearless Cities conference coming up in New York City this summer.

Together, they discussed how decisions get made within the party and how it relates to the social movements, what makes Barcelona unique and how people elsewhere can learn from Barcelona En Comú’s victory, and how to go beyond the local in municipal politics.

We’ve been really inspired by Barcelona En Comú, but are curious to know how your relationship has changed over the past year with the social movement that brought you to power.

First, it’s useful to separate party and government. For one thing, we don’t really like the word ‘party’. A lot of people in Barcelona En Comú participate in both Barcelona En Comú, the electoral project, and in social movements.

So it’s not like they’re separate entities. They’re not officially in any way affiliated, and in fact people are careful to keep the official separation. A lot of people who participate in both feel a lot of confusion and tension about that role. On an individual basis it’s quite difficult to resolve sometimes.

The other thing that’s useful to think about is that those relationships depend on the issue. When the City Hall is advancing and making progress and the demands of social movements—often very long-term and historic demands—and there’s progress, then the relationship is very positive, in the sense that the social movements feel represented.

They keep the pressure on to keep pushing the government but it’s where the government wants to go anyway. Regulation of tourism is one. Re-municipalization of water is another. Sustainable mobility. The feminist agenda. On those issues, the activists who participate in both Barcelona En Comú and social movements feel much more comfortable.

Then on issues where, either, in a specific moment, there’s a decision that people in social movements are not happy with, then the people who participate in both act as bridges, so that we know immediately what the relationship is, what the reaction is from the social movement, and also we can try to explain the decision.

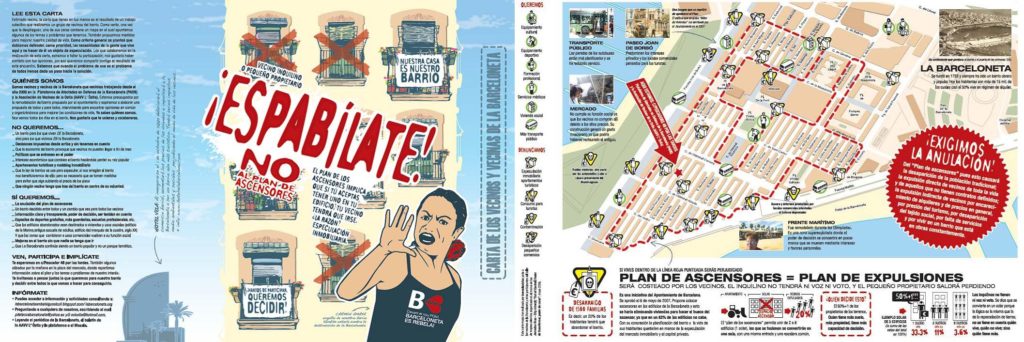

At least so it can be understood, or why it wasn’t possible to do what we wanted to do. Recently there was an example about the regulation of restaurant and bar terraces. The activist community, specifically the neighborhood associations, are really for strict regulation, because it’s private business taking up public space.

It’s really cheap to have tables in the streets. They want the prices to be raised and the tables to be reduced. It’s not actually a huge demand by the general population, but it’s a super-big issue in the activist community.

Then, just to have an agreement, our government made an agreement with the restaurant sector, which was far more liberal than the activist community wanted.

It’s impossible for the social movements to be involved in taking every single day-to-day decision that comes up in City Hall. So there’s moments where our people in City Hall make a decision and our organisation is like… “Why did that happen? We don’t understand. We don’t agree.”

Usually if the context is explained, people kind of understand what’s happened. But it’s a really complex ecosystem, basically.

Those are the kind of moments where there’s tension. I think it’s healthy and something we’re still learning how to manage. I think what’s most important is that it’s very much on an issue-by-issue basis.

Were there tensions between the party and the social movements when Barcelona En Comú entered government?

There was definitely a moment. When we were the activist underdogs in the campaign for municipal elections, it was relatively easy to get everyone on board campaigning to build the project.

And then in the election campaign, some of the most radical social movement people openly supported us, investing time and energy in the project.

And then when you go into government, there’s definitely a moment where a significant sector then steps back and says, ‘good luck, but I want to stay as an independent, non-partisan activist. My work here is done, and now I’m going to either do nothing or be super-critical or basically do opposition from outside’.

Or there’s people who stay involved, but then the first contradiction they encounter, or the first decision they don’t agree with, they can’t handle it, and they leave.

A lot of us have never been involved in party politics, let alone been in government, and our natural position is being anti-, being against, and protesting. It’s really difficult to suddenly have to be justifying the decision of the government, suddenly being ‘The Man,’ you know.

There’s people who are not happy or comfortable in that role, and they drop back. Which is completely understandable, but then at the same time, there’s part of me that thinks, you know, ‘Did you think it was going to be easy?’ Winning the election is going to be the first step. For a lot of people it seemed to be the last step.

That’s just where it begins, that’s when you start actually getting your hands dirty. Stepping out the moment you disagree is easier; it’s more comfortable; you could’ve maintained your ideological purity, or whatever. But if everyone did that, we’d be really screwed. I understand both decisions. I think anyone who stands for elections has to be aware that they’ll lose some people along the way.

You say the first step is winning the election. What’s the next step?

I was referring to really banal things: we went into government, but we have 11 councillors out of 41 in City Hall. Just trying to implement your manifesto when you need the vote of opposition parties to do it means that, inevitably, you’re not going to be able to do everything you wanted to do.

Or the fact that you get into City Hall, even a relatively powerful City Hall like Barcelona, and you realise that not all of the power is there. AirBnB has a lot of power. The Catalan government has a lot of power. The Spanish government has a lot of power. The media has a lot of power. Winning the election is the first step to getting anything done.

Barcelona is very different, isn’t it? There’s an inertia of social movements, the abundance of community spaces, and civil society is also really politicised. In North America and northern Europe, that’s all extremely rare. How would municipalist strategies differ in cities that have less of a vibrant political culture?

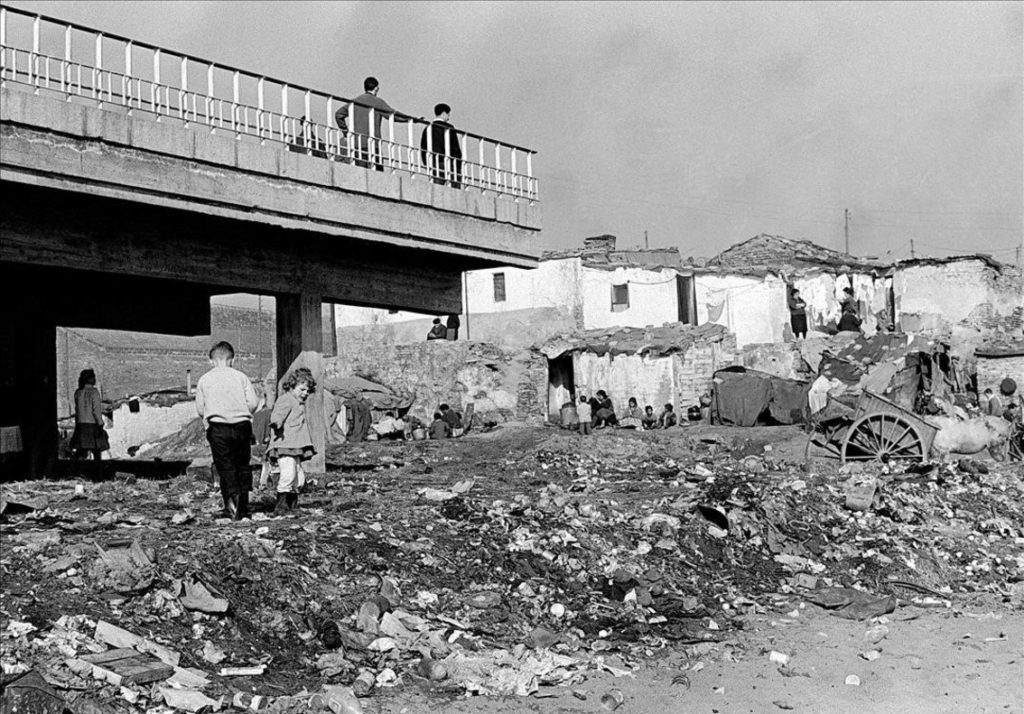

We had a different starting point. We had a crisis. I know the whole world had a crisis in 2008, but in Spain it was particularly bad and it was also combined with really scandalous political corruption on a scale that’s much more explicit than in the US, for example.

Politicians robbing public money, blatantly. Then we had the Indignados movement, which was in all of the major cities. You can do a map of the Indignados camps and the cities that the municipalist platforms won and they’re basically one-for-one.

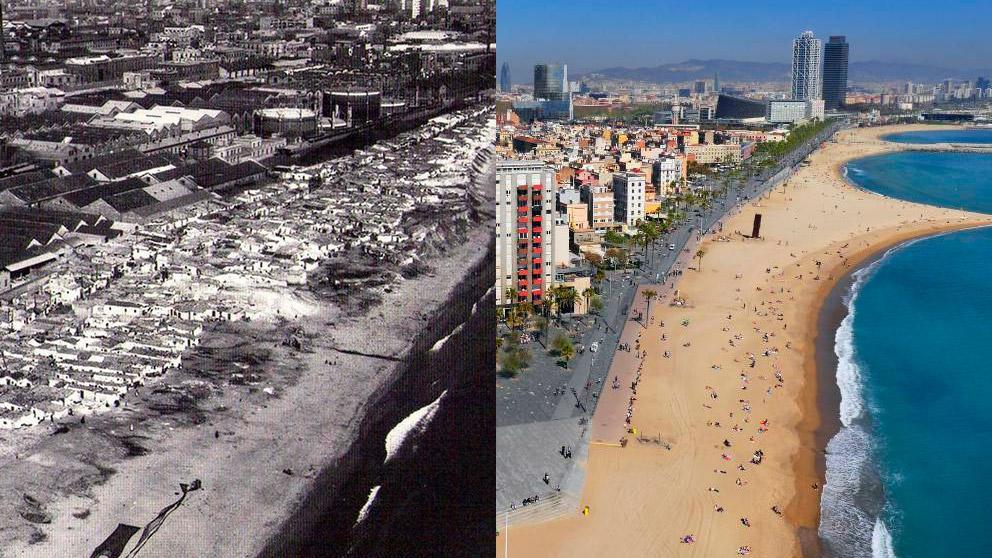

Then even before that: there’s a political culture in Catalonia that is very participatory. In Barcelona there’s a decades-long tradition of neighborhood associations. The reason we were able to set up a candidacy and win the elections less than a year later is because all of the organisation was already there. It was just a question of diverting it into an electoral project.

The work of actual construction was already done. It’s very difficult for me to advise anyone who’s starting from a situation different to that. I think it’s important that people understand that it wasn’t built in a year from nothing. And that, surely, the idea of doing that anywhere would be unrealistic.

Why do you think there’s a global municipal moment now?

I think people are focusing on municipalist politics because, if you look around the world, it’s what’s working. The panorama is so bleak. Even if you see political projects at a national level that seem to capture the imagination or bring people together like Bernie Sanders, or Jean-Luc Melenchon, or Jeremy Corbyn, they’re not winning elections.

Podemos hasn’t won an election. And like I said, that’s only the first step. It’s not enough. Municipalist projects are winning elections, and they’re also doing it in a different way. They tend to be more democratic, horizontal, participatory, feminist than the national equivalents.

For someone who cares about the way politics is done as well as just winning and implementing a progressive agenda, that’s an extra appeal as well. But I don’t doubt there’s a lot of people who would happily take a top-down patriarchal authoritarian left project at national level if it won.

I’m sure there’s a lot of people who would be like, ‘If I can win the whole country, implement my left-wing agenda from the top-down, I’d much rather do that than spend all my life in local assemblies’. I think there’s a lot of people who are municipalists by necessity.

One critique I’ve seen floating around is that this is an inherently localist form of political action. You won’t really change the way global capital works or the way the larger legal structures work. What would your response be to that?

I would laugh hysterically. There’s a lot of people who think in these very black-and-white terms that you’re either going to overthrow global capitalism (how?), or it’s not worth doing anything. Tell me the project right now that’s overthrowing global capitalism because I’m not aware of it.

I would much prefer a local project that achieves some small victories that show that change is possible than a national or global project that achieves absolutely nothing but has the ambition of overthrowing global capitalism.

How do you see a municipal strategy that goes beyond the local?

There’s two things. The first is working as a network. But, to be honest, right now, the only place where there’s a strong enough place for that to work is within Spain. In Spain we have a situation where all of the major cities are governed by citizen platforms [see this report by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation about municipalism in Spain].

That’s a base you can work from. Until we have more countries or regions where there is a critical mass of citizen-run governments, it’s not really realistic to expect a kind of prefigurative global municipalist government.

The other thing is that as soon as you start winning local elections, there’s a huge pressure to stand for elections on other levels. People start saying things like, ‘oh, there’s limits to municipal government, there’s things we can’t do, we have to stand for regional elections, the national elections’.

Beware of that, because for all of the limits that municipalism has it has some very special things about it. You can win, you can make changes; however small, you can change the way politics is done.

As soon as you start to invest energy and time in levels where that kind of thing isn’t possible, thinking that you’re going to overcome the limits of municipalism, you might end up doing neither. Which has been the experience in a lot of regional elections in Spain.

When you try to jump levels within a very short time frame. Some people are against jumping levels ever, some people are not against it in principle but are very wary of doing it too quickly. And then there’s some people who are municipalists of convenience, who see it as a stepping stone to standing for other elections. It’s very much a live debate we have at the moment.

How do decisions get made in Barcelona En Comú?

Usually what happens is that the coordination team of forty people decides to take big decisions to the plenary. The plenary is all the activists who are involved in Barcelona En Comú. Then part of Barcelona En Comú decides, ‘yes, we’re going to start the process to build a Catalan-level party’.

Then the final decision is approved by some sort of wider group of supporters registered on an online participation platform, which gives the final rubber stamp. Usually, all of these debates are also held within each local assembly, or each smaller unit.

The debates are very multi-level and occur over a long period of time. The thing is that once you start a process like that, it’s very difficult, somewhere along the way, to say, ‘oh, this isn’t going how we thought it would go, let’s call the whole thing off’.

So that’s kind of what happened when we tried to scale up to the provincial level. We started with this idea of a Catalan organization that would reflect Barcelona En Comú, and what we ended up with is not exactly that. We’re now having another debate about whether it could be redirected and improved.

I’m not quite clear how the democratic institutions in Barcelona En Comú really work…

There’s two things. One is the relationship between Barcelona En Comú and the city government on issues of policy and the action of the government. The other is decisions that are more internal to the political organization that don’t necessarily impact what the people in government are doing.

So, our official link with City Hall is the coordination team: 40 people, four are from city hall. The big issues, we talk about there. Then we have an assembly of representatives just from the neighborhood assemblies, then we have an assembly of representatives just from the policy groups—which are alternative spaces of interaction with city hall.

The neighborhood assemblies are interesting because the City Hall is organised on the basis of districts, which don’t necessarily correspond to our neighborhood assemblies.

There’s an awareness that, to be able to get anything done, you can’t be in an assembly deciding things all day long with other people. It’s usually particularly controversial decisions. It’s working well, I would say. I think we tend to focus on the cases where it hasn’t worked- which is normal, because that’s what generates the most noise.

But if you compare Barcelona En Comú to other organizations in other cities in Spain, at least, we have a very healthy organisation of over a thousand activists and we have governing bodies that are plural and made up of people from different political parties, all working together, all kind of focused on building the organization, implementing our program.

In other cities, either they don’t have the human resources for that to be possible because basically everyone involved in the platform went into city hall, so what was left behind was nothing on the outside.

Or, they haven’t been able to create a new organisation, and they remained as a coalition with different parties and movements who are constantly in conflict with one another. Luckily here we’ve had the critical mass to sustain an organization.

You’ve written a lot about the feminisation of politics. What does the institutionalisation of that look like, and how is it working out?

(Sighs) Terrible. Um. No. It’s difficult implementing it in your own organisation. And I think in City Hall, it’s a lot more difficult, because you’re dealing with an institution of the state, with thousands of people working in it.

We’re 11 councillors, we’ve probably got 100 people working in various appointed roles, but the crisis is really the crisis of time, and the crisis of work-life balance of councillors, our mayor, and everyone who’s working in city hall because the challenges are so huge and people are so—it’s not just a job to them.

They’re also activists. And the work is never done, we’ve got people working ridiculous hours, barely seeing their children. Burning out, and getting ill. It’s something that we at an institutional level, in terms of work-life balance is terrible.

In terms of policy, we’re doing pretty well. One of the first things we did was to set up a department of gender mainstreaming. As well as our department of feminisms and LGBTI, we also have another department where all municipal policy has to be checked for its gender impact.

In terms of participation and inclusion, and taking decision-making out of the city council chamber, we’ve done a lot as well. We’ve done lots of participatory processes. Not just, ‘come and participate’, but going out to groups of sex workers, or groups of disabled women, to ask them what they need and want.

Now we’re starting to do some citizen initiative mechanisms, so we have some mechanisms where if you collect 30,000 signatures you can put your initiative to a public vote. So all of that kind of stuff is moving forward nicely.

We’re basically feminising politics apart from ourselves (laughs). By ourselves, I mean the people working in City Hall. I was talking to Ada [Colau], who said, sometimes I just feel like telling people, after 5pm, everyone go home. Live your life. But it’s just not possible. So that’s one of the many contradictions that we’re trying to wrestle with.

How do we take lessons from Barcelona En Comú and apply them where we live?

What I would say – and I don’t really feel qualified to give advice – is to start small—not to just think immediately, ‘I have to stand for elections’. Ada Colau started with the PAH, she didn’t start by standing for mayor.

Every time you can show people that there’s a concrete way that they can improve their own lives, that’s how you can get more people involved, and then more people involved.

Most people don’t want to be involved in abstract political debates. They’re willing to spend their time on stuff if they see concrete results, however small. So that’s where I would start.

In fact in a lot of countries where there are municipal platforms now starting to stand for elections, they started as single-issue campaigns.

Barcelona En Comú is the electoral result of the PAH, let’s be honest. Some other movements as well. In Belgrade, it was against a waterfront development project. In Poland, it was against reprivatisation of public housing.

And often, what enabled a movement to start has been a single issue that people could rally around; and people could say this is about our city; there are more things we need to do; now we feel so empowered because we stopped that thing happening that we didn’t want to happen, or we made that thing happen that we wanted to make happen; now let’s win the whole city.

The Symbiosis Research Collective is a network of organisers and activist-researchers across North America, assembling a confederation of community organisations that can build a democratic and ecological society from the ground up. We are fighting for a better world by creating institutions of participatory democracy and the solidarity economy through community organizing, neighborhood by neighborhood, city by city. Twitter: @SymbiosisRev. This article was written by Aaron Vansintjan (@a_vansi).