by Boniface Mabanza Bambu

Colonialism with its dominant patriarchal and racist ideologies did not accept alternative ways of living. Its faith in the superiority of Western ways of thinking justified the violent destruction of original economic, social and ecological balances in all the regions of the world it invaded. Colonialism propagated an alienation from nature and an ecocide which nowadays finds its continuation in extractivism. As German philosopher Ernst Bloch put it, humans think they have the right to relate to nature like an occupation army relates to enemy territory. In many parts of the world, governments and mining companies act as if they had the God-given right to exploit the land at the expense of local communities and women in particular. Extractivist actors form the greatest threat to rural communities and women today, in particular where women’s land ownership is inhibited by tradition.

The wealth leaves the country while the social and ecological destruction remains on site.

In southern Africa many communities are being robbed of their land. National governments most of the times condone this practice of land grabbing due to the pressure of the transnational corporations that are being granted the right to extract minerals from the earth. Almost everywhere in the region people are under the impression that local communities cannot deny governments and corporations access to the land if it is needed for mining purposes. The governments let themselves be persuaded by memoranda of understanding by the companies that always promise to not only contribute to the wealth of the countries but also to directly improve the situation of the local communities. They promise the creation of jobs and to enhance infrastructures for education, health and transport. In reality nothing or only very little actually happens. Mining companies reap the profits and leave behind environmental degradation and social disintegration. Whatever governments collect in the form of license fees and taxes, if they get paid, often disappears into the private accounts of the elite of the national governments who have no social connection to the communities in question. The wealth leaves the country while the social and ecological destruction remains on site.

I was born in DR Congo, a very rich country when it comes to natural resources. I have seen many of these cases in different parts of the country and they occur in many other African countries. Because extractivism particularly affects women this article wants to emphasize the importance of tying antiextractivism and feminism in a postcolonial perspective.

The negative effects of mining particularly affect women as they are the ones who carry the responsibility for the survival of the family, and families are dependent on access to the land and water that is polluted and destroyed by extractivism. In extractivist contexts, it is generally women who ensure the survival of socially disintegrated societies; the men working in the mines suffer the effects of unhealthy working conditions and become prone to alcoholism, and women consequently dedicate more time to care work—while also facing an increase in domestic violence.

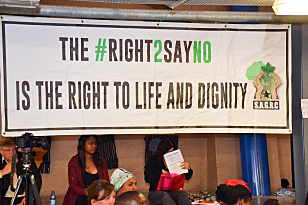

In light of these developments it is important to understand the scope of many local initiatives against extractivism. They are campaigning for realizing their “Right to Say No.” In South Africa for example, there is the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), a law that prescribes that mining companies must consult all concerned parties before starting their activities. Unfortunately, South Africa is not an exception to the general picture in which both national governments and transnational companies reduce the required consultation processes to mere formalities, which suggests that they hold colonialist beliefs about their unchallengeable right to access the land of local communities: landowners and users cannot refuse access. Faced with this existential threat, the communities affected by mining are rediscovering the value of solidarity. They are joining forces to claim their space in the centre of decision-making processes concerning their communities. Doing so they are discovering the integrative strength of women, whose voices have been marginalized for so long. Claiming space at the centre of decision-making means that they design their own options for developing their communities. They don’t see a future in extractivism.

The overcoming of extractivism and the dismantling of patriarchy must be understood as a joint struggle towards decolonization.

Not only does extractivism place a heavy burden on women and their local communities; it is also harmful to the environment. This combined assault on humanity and nature is not new, but rather indicates a continuation that dates back to the birth of the colonial project. Colonialism, understood as the commodification of the earth, its treasures, its flora and fauna and particularly its people for the economic benefit of the colonizing nations, still goes hand in hand with the domination over women and nature in the self-declared civilized nations. In the colonies people were alienated from nature and, by means of forced labor, induced to develop a violent relationship to nature. This relationship is being continued in extractivism. Therefore, the overcoming of extractivism and the dismantling of patriarchy must be understood as a joint struggle towards decolonization. Extractivism and its violent relationship with nature and people in the surrounding areas of the mines is a manifestation of skewed power relations, political structures, and economic dominance that maintain colonial logic and praxis. We can only successfully overcome the crises triggered by extractivism if the voices that have been marginalized up until now, especially those of women, claim a space in the center of the process of change.

Boniface Mabanza Bambu is a theologian, philosopher and literary scholar from DRC. He works for KASA, Kirchliche Arbeitsstelle Südliches Afrika/Ecumenical Service on Southern Africa in Heidelberg, Germany where the main focus of his work is on apartheid and post-colonialism.