by Owen Watson

If the chalk memorials wash away on the downtown road, formerly Fourth Street, in Charlottesville, Virginia, it may seem like any ordinary block with a cafe and bookshop. Today, Heather Heyer Way remembers the life lost when a white supremacist crashed his car through the antifascist lines celebrating after they successfully drove off far-right and neo-Nazi groups at the 2017 Unite the Right rally. This individual act of violence, which injured 28 and killed one, draws from a long history of the automobile serving to protect spaces for whiteness.

The car remains a weapon of choice against anti-racist protestors as the uprisings against systematic racism ignited by the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor stretch into their fourth month. On May 28th in Los Angeles, police officers drove their car through a group of protestors, speeding up to throw a man off the hood; the next day in Denver, a woman intentionally turned around to hit a protester with her SUV; the day after that, in Brooklyn, the officer riding in the passenger seat of a patrol car opened their door to strike a protester as they drove past. Further examples in Brooklyn (again), Portland, Tulsa, and San Jose make this a disturbing trend with over 69 such attacks occuring since Geroge Floyed was murdered in late May.

Fascism and the Automobile

The connection between automobiles, violence, and fascism begins in the 20th century. An investigation by The Nation uncovered how Ford Motor Company and Nazi high command were intimately linked. Henry Ford, a known anti-Semite, built a factory in Cologne, Germany in 1931 and provided support for the Nazi state into 1942, almost a year after the United States declared war on Germany. General Motors was also complicit in the Nazi war effort, obfuscating their ownership of German-made Opel while they knowingly allowed their factories to switch to military armament production for the Wehrmacht.

In Italy, the automobile itself became a symbol in the blending of the futurist and fascist movements in their shared rejection of history and chauvinistic desires for speed and social ‘purity’. The fingerprints of futurism can be found in the Nazi warfare tactic of blitzkrieg (prizing speed and suprise) which used Ford trucks for about one third of the vehicles involved.

The car was used as a social tool for white interests in the United States following the war, as the automobile commute enabled a new form of segregation in sprawling suburbs. ‘White flight,’ the mid-century process of white populations moving out of American cities, occurred alongside the systematic divestment of inner-cities which were increasingly populated by Black communities migrating north, away from the Jim Crow South. Through racist policies like redlining, discriminatory bank lending and zoning practices, Black communities were largely excluded from the post-war affluence while much of the white working class gained access to financial services to start building generational wealth. As wealthy tax bases shifted to the suburbs, city budgets and services stagnated while ‘urban renewal’ projects often meant highways would be built on top of Black communities.

The automobile, therefore, represents two inextricable forms of violence: the slow process of gutting the public city for racialized private wealth, and the acute violence of fascist car attacks. These are mirrors, reflecting and feeding back the images of one another. The logic of the car in America is implicit in the logic of white supremacy. On a mass scale, the automobile works to emotionally and physically separate groups from the unequal violence of a racialized system. This logic also extends to the individual in the emotional separation from the mechanisms of fast, immediate violence.

Marketing violence

The ‘alpha male’ mentality fascists are obsessed with informs the marketing strategy for many car models. The specific car driven in the Charlottesville attack was the 2010 model of the reissued Dodge Charger, a muscle car marketed as a hyper-masculine vision of an allegedly bygone age of American liberty. The current tagline for the Charger is ‘Domestic, not domesticated,’ a nod to the patriarchal embodiment of masculinity against the ‘globalist’ economy of foreign manufacturing.

The Charger is also the country’s best selling model of police sedan. With no hint of irony, Dodge even created a small fleet of stormtrooper-themed Chargers to celebrate the release of the Star Wars: The Force Awakens film in 2015, mimicking the foot soldiers of the fictional fascist Galactic Empire. A year before that, the head of government fleet sales for Dodge explicitly connected police intimidation with its marketing to a wider consumer base: ‘You hate to see a Charger Pursuit grille in your rearview mirror. …we think there’s a lot of carry-over in terms of the macho appeal of the vehicle.’

The message here is simple: the Charger is an embodiment of white, male, state-sponsored violence. This aesthetic marketing of a police vehicle to the masses is another example of the militarization of civilian spaces, one of the dominant features of post-9/11 America. It is also a classic marker of the advance of fascism where violence and militarism are normalized in everyday life. Charlottesville’s right-wing murderer tapped into all of these forces, namely the nexus of a patriarchal capitalism and statist militarism that continues to guide an implicit understanding of who violence should be directed against, and who it should be wielded by.

American Violence and the Anti-Martyr

Dependence on the car obscures the everyday violence of driving. In 2018, 36,560 people died in car crashes in the United States alone, making driving the second-leading cause of accidental death. In India, almost 150,000 people died in traffic accidents during 2017. Nigeria has one of the highest rates in the world with over one death per year per 100 cars. Driving is the largest normalized risk in modern life. While often acting as a site of insulation for white individuals, the car can be a site of racial profiling where non-white drivers are stopped by police at higher rates, too often leading to fatal violence in the US.

As one of the ultimate status symbols in capitalist society, the car is an embodiment of social atomization and private enclosure of individuals, families, and groups. To drive is to intentionally hold death at arm’s length; by the risk of driving itself, and the physical and emotional insulation of the cabin from the outside world — a degree of separation between a potential killer, their killing tool, and those to be killed.

This, finally, is the concrete connection between the car and right-wing violence that neatly fits in the white American psyche. For the maintenance of settler ideology, a physical and emotional separation from the justification for structural violence and the violence itself is needed. This degree of separation is a constant in American state violence, from the drones that fire silent death in Syria to the American streets where police run over protestors. And, not surprisingly, it is expressed in both American right-wing acts of violence and police brutality through a desire by the attackers to be as physically protected as possible.

Consumer vehicle ramming attacks began in earnest during the late 1990s in occupied Palestine and have expanded worldwide, taken up by different ideological forces including ‘Jihadists, anti-Islamists, right-wing Christians, and unbalanced members of the public.’ When the assailant is non-white and acting without institutional power, they are usually portrayed with the broad strokes of ‘terrorism’ by Western media. Meanwhile, white supremacists like the Charlottesville attacker are often depicted as ‘lone wolves’ or ‘bad apples,’ despite the clear structural roots of their action. In the months after Black Lives Matter protests in 2016, six states considered laws to protect drivers who run over protestors from prosecution, referring to demonstrations that block traffic as ‘terrorism’. As systematic racism is being directly challenged, reactionary forces use violence to subvert public opinion while police are more explicitly acting in line with the larger neo-fascist project in defense of the status-quo. Seeing themselves as firebreak between ‘order’ and ‘chaos,’ a thin blue line which is drawn deadly on the pavement and unaccountable to democratic processes. This is the logic of fascism and is being encouraged by the President of the United States who claims the suburban way of life is under attack and brands anti-fascism as terrorism.

Scholar Achille Mbembe’s ideas around martyrdom are particularly illuminating when it comes to the issues of insulation and vehicular violence. Contrasted with the figure of the ‘suicide bomber,’ the American far-right and police vehemently protect their own bodies with armor and vehicles. Fitting with American’s elevation of ‘heroes’ amid the desire to uphold a certain social order — an inherent flattening, widening, and depersonalizing of the martyr. The right-wing propagator of violence and the police officer alike are part of imagined ‘brotherhoods’ on an invented battlefield made manifest only by the violent actions they carry out.

What this truly represents is an anti-martyrdom: a feature of a country that glorifies endemic and ‘heroic’ bodily sacrifice while deeply fearing death or any major change that would challenge those systems. Mbembe describes how the logic of survival and heroism intersect:

“[The] moment of survival [is] a moment of power. In such a case, triumph develops precisely from the possibility of being there when the others (in this case the enemy) are no longer there. Such is the logic of heroism as classically understood: to execute others while holding one’s own death at a distance.”

These acts of violence we see, whether in Charlottesville or in the ongoing protests against police brutality, are laden with the power of historic white supremacy. The power of mismatched tools of violence between attacker and subject (the car vs. the protestor), and the one-sided power to deal death and to survive. This is the type of unequal violence that the ruling class carries out against the underclasses, a deadly enforcement of the racial, economic, and social status-quo.

If neo-fascist violence in America is about preserving the mythological ‘White Christian Nation,’ it should not be surprising to see police adopting the tactics of neo-fascist violence. The police themselves trace their roots back to slave patrols. The car is a shared tool in the merger. Its rise intertwined with evolving racial oppression, and fits into the psychology of white racial terror by distancing and protecting its perpetrators from the violence of their actions while reinforcing social categories of an ultraconservative worldview. The car, the most defining object in 20th century American prosperity, is now a viscerally violent encapsulation of the failed 21st century American state.

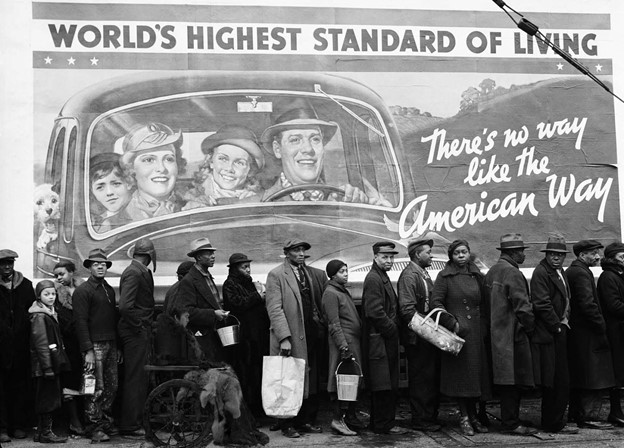

There’s no way like the American way

Margaret Bourke-White, the first woman to take photographs for Life Magazine, took a depression-era snapshot of an all-Black bread line standing in front of a billboard featuring a smiling white family in a car. “There’s no way like the American way,” the billboard reads, as the white nuclear family drives through the idealized suburban countryside and straight into the reality of the bread line. This is a symbolic photograph for our time, though it was taken in 1937. The car operates as a tool for acute white violence and flight as well as the insulation of whiteness through physical and metaphorical mediums, “world’s highest standard of living,” emblazoned over a strict racial separation in a country of destitution for so many. It has been over 80 years since the photograph was taken. The car as a symbol of freedom, safety, and violence may have evolved in small ways, but the American racial landscape remains unequal and violent.

The current protests against police brutality are not simply a symbolic challenge to the structural violence that the American street embodies. They are also processes of a physical recapturing of public space – for solidarity, grief, anger, and celebration. It should come as no surprise that centuries of white supremacy should so violently respond to that challenge with a tool – the automobile – that has been so central to fulfilling its goals. Yet even in the face of terror so often committed by vigilantes and the state, the unwavering numbers of protestors are a source of hope: that one day, our children will walk safely down carless avenues, knowing of the struggles that tore down and replaced the violence and injustice of the old world.

Owen Watson is a writer working in political ecology and the environment, especially as they relate to political economy, extremism, and power. He recently completed a graduate program at the University of Michigan, where he concentrated in Environmental Justice. Follow him @elementsofguile.